Introduction

Public hearings are a distinctive democratic process as they bring together politicians, public administrators, industry, experts and citizens into dialogue together over policy issues. They are a recognised, pivotal and often required, part of policy and planning making process in the UK, and more widely (Klinke 2009, Baker et al. 2005). Much of the empirical research on public hearings (Innes & Booher 2004; King et al. 1998; Baker et al. 2005), indicates that they are ineffectual, unsatisfactory, and illegitimate ways of formulating decision making. Yet the verdict on public hearings may well be different if we view them as part of a wider deliberative democratic process. Indeed, the value of public hearings has been acknowledged by deliberative theorists (Mansbridge et al. 2010; Hendriks 2011). It could be argued that as more innovative types of deliberative processes struggle to make a policy impact (Elstub & Escobar 2019; Hendriks 2016) public hearings are well positioned to enable multi-stakeholder deliberation to make a credible impact due to the fact that public hearings are a required process in policy and planning systems already. There is some empirical research viewing public hearings as part of a deliberative democratic system (Fournier et al. 2011; Schylter & Stjernquist 2010), yet for hearings to be integrated as part of a deliberative system, it is vital to determine what works and what their role would be. This includes where hearings are best placed in the policy process and how they can be effectively coupled or linked with other democratic processes, including representative, direct and deliberative processes.

This article seeks to contribute to the field by exploring the democratic quality and potential of public hearings. To do this, I introduce the Democratic Standard Enactment Index (DSEI): a systematic way to compare democratic institutions’ capacity to enact core democratic norms of inclusiveness, popular control, transparency, and considered judgement (Smith 2009). This index is applied to four case studies on public hearings. The article finds that the democratic norms are consistently fulfilled by the hearings. Moreover, their perceived limitations could be overcome by changes to the format and by linking the hearings with other democratic processes. In turn, public hearings can potentially bring some benefits to representative, deliberative and participatory processes. These findings will be of interest to public administration and public policy scholars broadly, but those interested in public hearings and deliberative democracy specifically.

Background

There has been a wide acceptance of deliberative processes and practices, meaning that deliberative forums have been adopted in many countries. Deliberative democrats—practitioners and academics—have rightly moved to evaluating and assessing the success of such processes (see Bächtiger & Parkinson 2019; Deligiaouri & Suiter 2021; Michels & Binnema 2019). This has enabled researchers to set out best practice, innovate around new formats, and observe deliberative processes working in conjunction with other democratic processes within various political systems (Boswell et al. 2023; Demski & Capstick 2022; OECD 2021). Due to the complexity that surrounds deliberative institutions, each face various and diverse problems. It is therefore important to ascertain what role each democratic institution is able to fill when coupled (Hendriks 2016), sequenced (Goodin 2005) or connected with other democratic institutions. Yet there is still little understanding of how various institutions can combine to overcome the weaknesses of each (Elstub 2014; Warren 2007).

Smith’s (2009) ‘goods-based model’ provides a normative framework which enables researchers to understand how variations in institutional design might affect the institutions’ ability to fulfil the democratic goods that are valued by deliberative democrats—and potentially how weaknesses could be overcome or improved. Therefore the realisation, or partial realisation, of these goods indicates that a democratic institution is of some worth. Enacting all democratic goods at any one time, at each stage of the democratic process and each level of governance is understandably problematic for any one mechanism, be that a deliberative one or otherwise. By combining various mechanisms though, deliberative democrats believe that each will fulfil a different but equally vital role in the deliberative process (Elstub 2014; Goodin 2005).

Public hearings are an embedded part of many political systems and take place all over the world in most political systems (McComas et al. 2010), and yet little attention has been paid by deliberative scholars. Despite this, their deliberative potential has been acknowledged by a number of prominent theorists (Fung 2006; Gastil & Black 2007; Hendriks 2011; Mansbridge et al. 2010). Moreover, their usefulness in the decision-making process has been particularly noted within a number of key studies (Fournier et al. 2011; Karpowitz & Mansbridge 2005; Klinke 2009; Schylter & Stjernquist 2010). For hearings to be integrated into the deliberative democratic field, it is vital to determine the level of legitimacy, justice and effective governance that is drawn from the public hearing process (Fung 2006: 66). By considering whether hearings can enact any combination of the democratic norms allows insights on both theory and practice (Smith 2009). The next section provides an overview of public hearings.

Public hearings

Public hearings are a self-selecting participatory process that welcome a variety of actors to identify and focus on issues that require discussion (Johnston et al. 2013; Wraith & Lamb 1971). A hearing is used to discuss issues of public concern and designed to incorporate public participation or public opinion into decision-making (Catt & Murphy 2003). This offers an opportunity for members of the public, as well as other group interests, to voice their opinions and to be heard by decision makers (Klinke 2009). Most hearings will take the form of a question and answer session between a selected panel and an audience, with a chance for the audience to respond to the panel once a question has been answered. A chairperson mediates this exchange. Abels (2007: 108) describes them as having five normative functions: to inform affected citizens; to inform the administrator; to represent stakes; to legally protect the applicants and those who feel affected; and to increase the legitimacy of the final administrative design. Therefore, hearings’ capacity is multifaceted as they can be used at multiple points of the policy making process and at different levels of governance, which could potentially highlight their suitability to be linked with other processes.

Yet, Innes and Booher (2004: 419), among others (Baker et al. 2005; King et al. 1998), believe existing methods of public hearings are ineffective and illegitimate ways of formulating decision making, despite being ideally positioned to make an impact. Hearings have been accused of being tokenistic and ineffectual processes (Young 2000: 4), described as a ritual: ‘a largely symbolic activity with little concrete meaning’ (McComas et al. 2010: 122), and of failing to accommodate a satisfactory level of debate between officials and citizens (Kemp 1985: 177; Lando 2003: 76). Klinke (2009) adds that the attendees do not represent a true microcosm of wider society due to the self-selective nature of those who participate. We are reminded of the risks of self-selection by Fishkin (2009: 13–23): confident speakers may dominate the discussion or even crowd out less confident participants. Further concerns have been raised by Mikuli and Kuca (2016: 15) who observe, ‘a significant obstacle to the real impact of the public hearing is…the frequent failure of government officials to perceive members of the general public as equals. As a consequence, it is difficult for citizens to share authority or decision-making power and to effectively assert their ideas’. Baker et al. (2005: 491) agree and state that officials do not want to share decision-making power. This is significant when considering what influence participants of a hearing might exert over a policy decision or development.

The findings are not always negative; a less jaundiced view is that hearings legitimise decisions made by dominant political and economic players by encouraging transparency and accountability (Schylter & Stjernquist 2010). Hearings are a recognised process where citizens feel they can be heard and hold decision makers to account, as Klinke (2009: 353) tells us, ‘affected and interested people perceive the public hearings as one of the cornerstones in the public participation’. Indeed, when hearings are not made available to citizens during a controversial planning or development project, the public can become reactionary and resentful (Karpowitz & Mansbridge 2005: 352). Furthermore, public hearings have been noted as playing an intrinsic part in making decision-making processes more participatory and inclusive in a number of studies (although details are often sparse) (Dryzek 2005; Fournier et al. 2011). In addition, Gastil and Black (2007: 24) consider that hearings can facilitate ‘mutual comprehension’ which is achieved through the ‘rigorous, thorough assessment of pros and cons that yields a well-informed and reflective decision’. Abels (2007: 108) too notes that hearings are the only participatory model which links ‘public administration and decision-making’. Therefore, they have the potential to facilitate administrative governance in an open and transparent setting by connecting decision-makers to their public.

Importantly, hearings allow people to voice divergent interests thus bringing conflict and disagreement to light which can sometimes be pushed aside by processes striving to reach consensus, such as those focusing on deliberation (Karpowitz & Mansbridge 2005). From this, communication can occur, which may or may not be adversarial in nature but nonetheless requires an arena to be accommodated and explored. While advocates of pure deliberation caution against participants entering dialogue with fixed mindsets and a clear stake in the outcome (Cohen 1997), the public hearing offers a setting which could accommodate a different type of communication. Linking the hearing with a deliberative setting could potentially provide options and choices for citizens to participate. Therefore, there are specific features which hearings bring to the democratic decision-making process that deliberative and representative processes may fail to.

In order to ascertain if hearings could be coupled with deliberative processes or within a deliberative system, it is first required to consider whether they should. By applying a comparative framework, it can be determined whether hearings have the potential to host deliberative democratic goods and therefore, serve a purpose within the discursive sphere. The following framework was designed to evaluate the potential of public hearings but it could be adjusted to compare any type of democratic innovations (mini-publics, participatory budgeting, digital innovations and so forth). The next section introduces the framework and explains how it is applied to the case studies.

Methodology

In this section I set out the research method, starting with the overarching comparative framework, the DSEI, then provide an overview of the cases and the rationale for case selection.

Democratic Standard Enactment Index

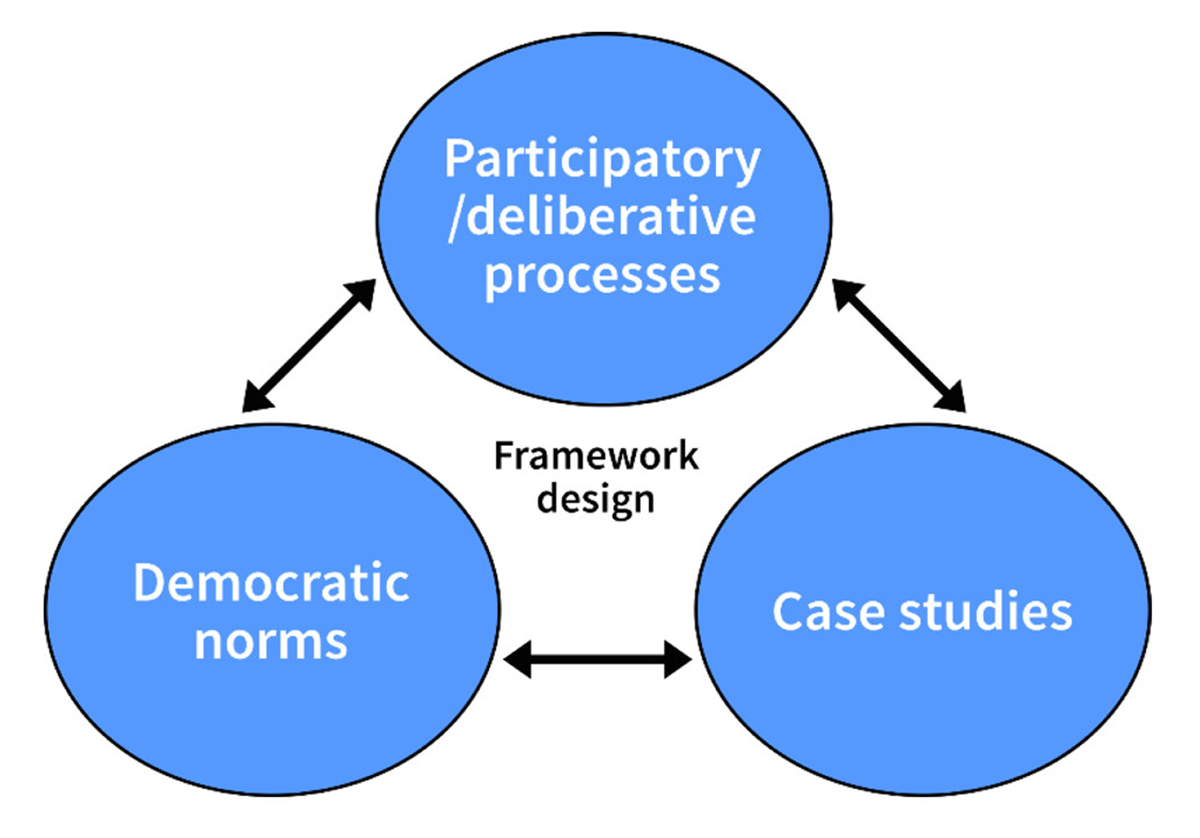

Much work has been done to produce evaluations, frameworks and standards by which to assess the success of individual deliberative democratic processes (Knobloch et al. 2013; Spada & Ryan 2017). The Democratic Standard Enactment Index (DSEI) contributes to this growing set of evaluation tools and has been designed in order to carry out a comparative exploration of public hearings. This offers a systematic way of extracting relevant information about individual cases by developing an operational set of measurements that enables comparative analysis between cases. The democratic norms of (inclusiveness, popular control, transparency, and considered judgement), are adopted from the work of Smith (2009) and Elstub (2014). Figure 1 below shows how the DSEI was designed, informed by the researcher’s knowledge of participatory and deliberative processes, democratic norms and the case studies themselves.

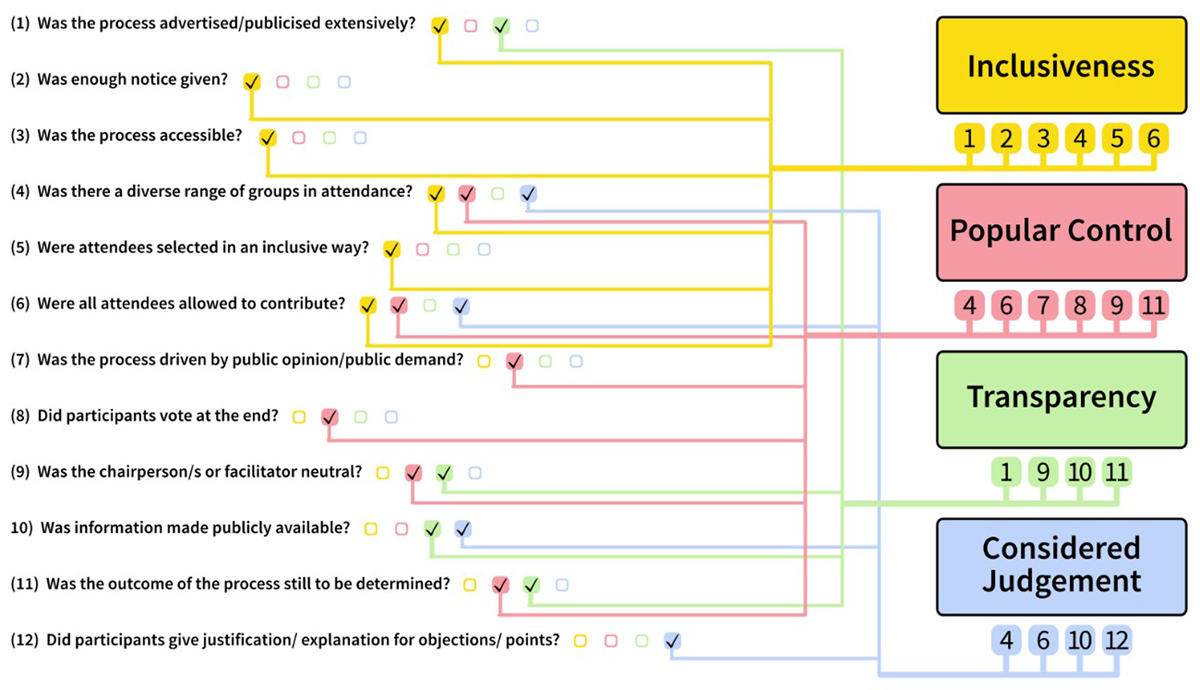

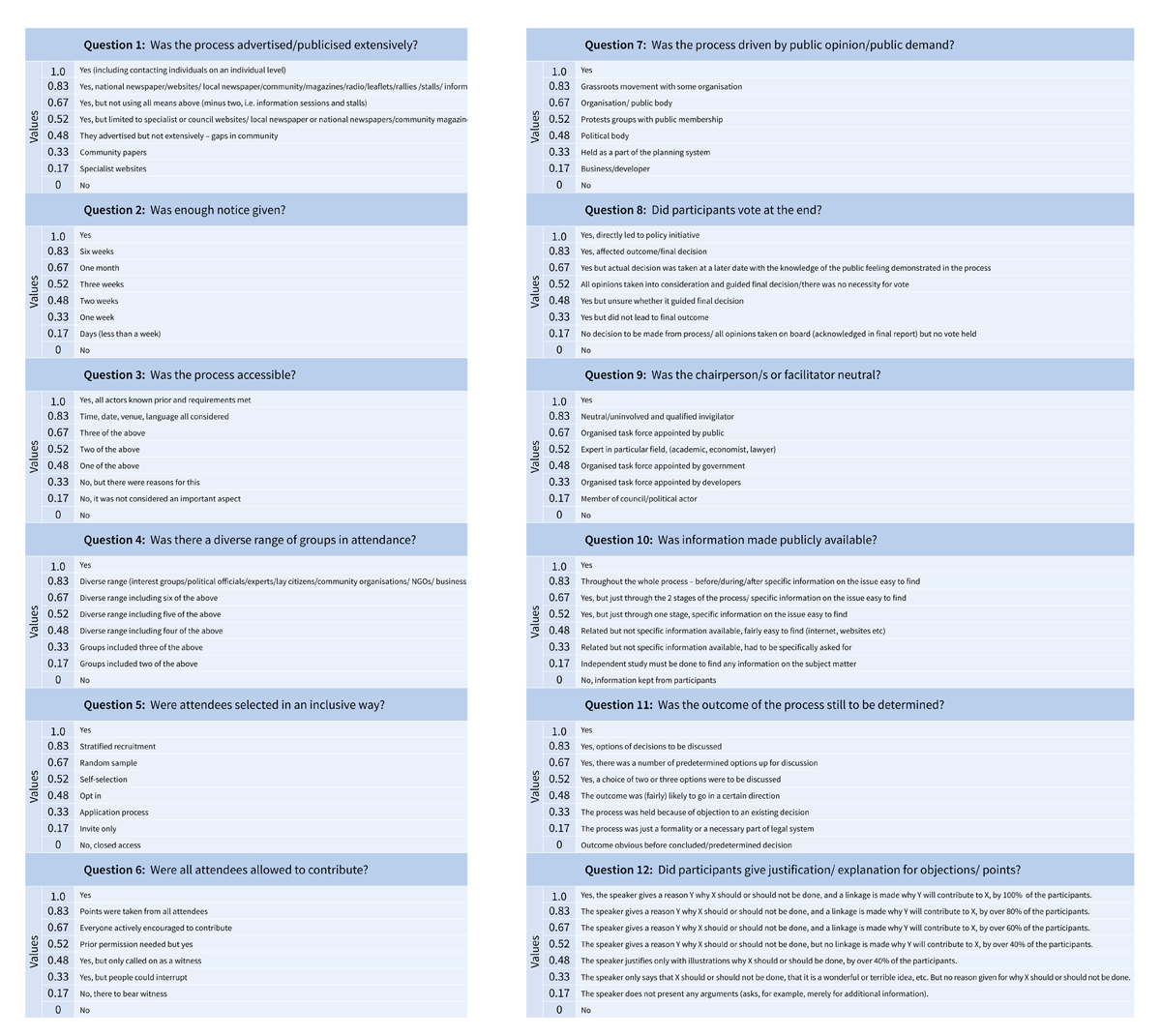

The DSEI (shown in Figure 2) helps us to view case studies in a holistic fashion, both in terms of how they could enact the democratic norms and what could be learned from them about specific features of hearings. Figure 2 sets out a series of 12 questions which narrows the focus of a case study analysis, specifically for public hearings, and accommodates the extraction of data explicitly related to the democratic goods. Each question is designed to establish whether aspects of the democratic good have been considered or upheld.

Each of the case studies has had the framework applied and ‘measured’ for how well it has performed. The measurement is low, medium-low, medium, medium-high and high, and explanations for how this measurement has been applied are given in Figure 3 (see appendix 1, measurement adapted from Ryan and Smith 2012). The response to each of the questions in Figure 2 and the allocation of a score (to what extent it meets the criteria) has been determined on how far the case study fulfils the questions and which answer it best resembles. Figure 3 provides a brief overview of how each measurement was determined but see Lightbody (2016) for more details. Applying scores across an index can risk missing nuance and complexity (Boswell & Corbett 2021) but a deep knowledge of the cases is required by the researcher to gather the data and answer the set questions.

‘Inclusiveness’ within democratic institutions is the equal rights of all to participate, according to Smith (2009: 20) and Knight and Johnson (1997: 280) think it is the ‘equal opportunity of access to political influence’. Therefore, in order to ascertain if people were able to access the process, questions 1, 2 and 3 focus on whether the process was easily attended in terms of knowing it was taking place, the amount of notice given and whether it was accessible. Individuals will be more supportive and invested in a system that they have a chance to participate in. In addition, if the public is allowed to deliberate on certain issues the outcome is more likely to reflect the ‘general will’ (Femia 1996: 373). Dryzek (1990: 202) believes inclusiveness is a fundamental condition for a more legitimate and trustworthy form of political authority. All citizens should have the right to be heard with an equal right to challenge decisions and put forward ideas. Questions 4 and 6 seek to determine if a diverse group of people attended both in presence and contribution, while the 5th reviews the selection process.

‘Popular control’ is a central part of the decision-making process. For Smith (2009: 22) popular control may not necessarily include conclusive outcomes, as institutions may not ensure decisions. The control instead resides in influence over the decision-making process and the ability of citizens to operate alongside government officials and public authorities (Smith 2009: 24). This power will become apparent through the agenda setting power that the public wields. If citizens hold agenda-setting powers, it would be placing significant control in their hands; as such, conditions within that participatory process would have to be conducive to realising and protecting this popular control. Popular control is thus measured through the diversity of attendees (4), and the impact the public had on the agenda (7), the debate (6) and the outcome (8 and 11). The role of chair is also paramount to ensure fairness and that no individual or group dominates (9).

‘Transparency’ is necessary within democratic institutions as it ensures that there is a degree of openness between participants throughout the decision-making process. Smith (2009: 25) says transparency is vital for citizens for a number of reasons: so individuals understand how the issue being considered has been selected, who is organising the proceeding and finally, how the outcome of proceedings will effect political decisions. This creates a deeper understanding of how conclusions are arrived upon and decisions made, which in turn assures individuals that their participation is crucial (Smith 2009: 25). Therefore, transparency is key to improving democratic processes and legitimising decision making. Figure 3 shows that this is measured through the chairperson (9), the information available which would allow people to contribute appropriately (1, 10) and that the outcome had not yet been decided (11).

‘Considered judgement’ is often overlooked within the democratic process. While inclusiveness and popular control are often perceived as the vital goods of democracy, the legitimacy of decision making is ensured by the ability of citizens to make reflective and considered judgements (Smith 2009: 24). Thus considered judgement cannot be achieved merely through democratic institutions such as elections and referendums. The legitimacy that is considered to result from deliberation can only be determined through the understanding of technical details by the relevant participating citizens (Elstub 2014: 398). Crucially, while we cannot be assured within the public hearing context that everyone is approaching policy with an ‘enlarged mentality’ (Arendt 1968: 220), what can be assured is that the participants are being exposed to various groups and perspectives. Through collective and public debate, a variety of perspectives are highlighted and discussed.

Therefore, crucial for this is that the necessary information is available so that participants can contribute effectively (question 10). Through collective and public debate, a variety of perspectives are highlighted and discussed, measured through the diversity of opinions offered (4 and 6). People are able to effectively reflect on issues when they are exposed to opinions which are not their own. Question 12 seeks to determine how sophisticated the speech acts are and if participants offer justifications for their standpoints (Steiner 2012). The justifications given can be explicit or implicit as long as all participants understand the link between demand and justification(s). For hearings this is vital as it includes lay and official persons and it is probable that some participants will not always understand technical terminology and reasons and justification will help to illustrate the meaning.

The current evidence on the link between public hearings and democratic norms is mixed and does not take account of the various features of hearings and how they can be used differently, which is explored in the next section.

Case study selection

Information needed to answer the DSEI questions on each hearing was collected from books, journal articles, reports, newspapers articles, letters to newspaper editors, emails, speaking to organisers and participants, hearing minutes, hearing statements, government websites, interest group websites, audit reports and social media activity around the hearings where available (Twitter and Facebook). A significant challenge to collecting data on public hearings is that much of the documentation does not remain online for long. Many of the reports and summaries, including minutes, are no longer available from council or government web pages.1

Case studies

Following a systematic search of evidence across multiple databases, using key words, the research was undertaken through a scoping review of case studies in order to gather evidence of type, format, use, cause, outcome and so forth of four public hearings. The case studies included in this research have been chosen specifically because they represent different stages of the decision-making process, been held at different levels of governance, and represent the various types of hearings, as Table 1 shows table 1 is above.

Case study information (table adapted from table 5.1 in Lightbody (2016: 88): a detailed breakdown of all case studies is available in Chapter 5).

| CASE | A | B | C | D |

| COUNTRY | Scotland (2014) | BC, Canada (2004) | European Commission (2013) | United Nations (2011) |

| LEVEL OF GOVERNANCE | Local/devolved | Local/federal | Regional | Supranational |

| TYPE | Quasi-judicial | Legislative | Legislative | Quasi-judicial |

| PURPOSE | Planning approval | Information sharing and gathering | Information sharing and gathering | Review of national policy decision |

| FORM/LINKS WITH OTHER PROCESSES | Inquiry. Key component of planning process | Sequential. Linked to deliberative and direct democratic processes | Coupling institutions. Hearings all feeding into knowledge exchange process | Inquiry. Sequenced with representative democratic processes |

| NUMBER HELD | 1 | 50 | 3 | 1 |

| FACILITATOR(S) | Reporter (appointed by Scottish Government) | Several chairs (members of the citizens’ assembly) | Several chairs (external professional experts) | Several chairs (committee members) |

| ORGANISERS | Government body | Organised task force of citizens | Organised task force of experts | Compliance Committee |

| CAUSE | Planning law | Consultation | Consultation | Public pressure |

| SUBJECT | Wind farm development | Electoral reform | Advanced manufacturing | Aarhus Convention |

Table 1 sets out the key features of the hearings. These include the level of governance, the type of hearing, the purpose of it and the form it took (was it linked to other processes), the number of hearings that were held, the chair—whether it was a single chair, a panel or a committee—who organised the hearing, the catalyst for the hearing and finally, the subject of the hearing. While the sample size is small it allows us to explore and compare a variety of hearings’ features and procedures.

The first case study was held in Scotland, UK in 2014 (A). In some ways, this was held as a standalone process which facilitated public input into a windfarm development, in accordance with planning processes in Scotland. Due to its location there was significant local opposition, but the development also received wider attention from walking groups, bird watching groups, and environmental groups. Case B public hearings were held in British Columbia (BC), Canada, as an additional public format to the wider consultation being held on electoral reform at that time. These hearings were held as part of what could be considered a deliberative sequence of consultation and public participation (see Ratner 2005). The hearings fed directly into citizens’ assemblies, ensuring that a wider demographic was consulted beyond the deliberative process, and ultimately informed the government through the BC citizens’ assemblies (BCCA) recommendations (although the recommendations from the hearings did not align with those that came from the CA). There was also a referendum following the completion of the public consultation. Case C was held as information gathering and sharing exercise, made up of over 100 business leaders, stakeholders, academics and experts from 16 European countries. This included a coupling of three processes which fed into each other to inform the European Commission (EC). The hearing at the United Nations (UN) (D) was held by the Aarhus Convention in response to a complaint by members of the public against the Scottish Government and Edinburgh Council. Case D was one of a sequence of processes, fed into by multiple actors, including various formats of evidence, and reviewed decisions made by the Scottish devolved government and made recommendations regarding Scottish and UK policy making.

As Table 1 shows, two of the hearings are legislative (B and C) while two are quasi-judicial (A and D) (Lightbody 2016: 26–7). There is a divergence in purpose of some of the hearings ranging from planning approval to information sharing and gathering, and one reviews an existing policy decision. Therefore, this offers insight into the various points a public hearing can be held during the policy-making process: agenda setting, decision-making process, and reviewing decisions. Two of the public hearing processes make use of more than one hearing, based on the jurisdiction that it was covering (B and C). All feed into other democratic processes enabling some insight into whether sequencing or coupling hearings with other processes can and should be done. Further comparisons can be made on the facilitators, who range from a single reporter, chair, to a panel. The organisers of the event and the cause stemmed from a variety of sources including government officials, organised committees and interested non-political groups, while the catalyst for the hearings were planning laws, public pressure or required legal consultation. The hearings focus on manufacturing and planning, alternative energy supply and electoral reform. The hearings were held between 2004–2014.

The next section presents the key findings from the analysis.

Findings

Inclusiveness

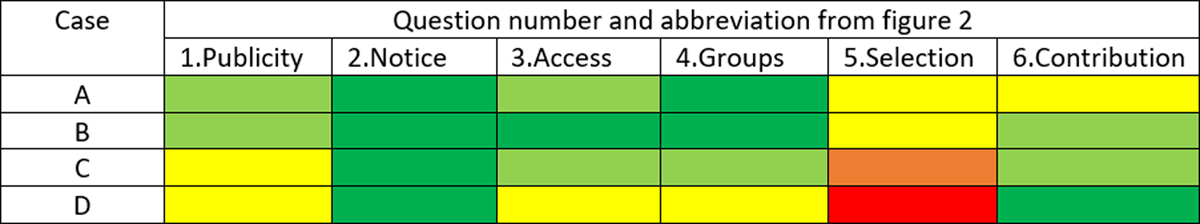

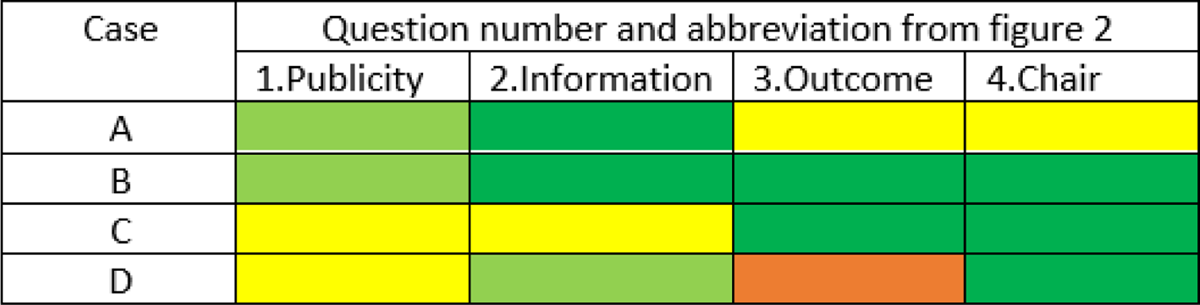

Table 2 below sets out the membership given to each hearing in respect to the questions set in Figure 2, employed to assess inclusiveness, and possible answers in Figure 3 (Appendix 1).2 The case studies are denoted as letters A–D and the columns are numbered to represent the column number and not the question from the DSEI that it refers to.

Questions 1, 2 and 3 in the DSEI focus on whether the process was easily attended in terms of knowing it was taking place, the amount of notice given, and whether it was accessible. Questions 4 and 6 (see Figure 2) seek to determine if a diverse group of people attended both in presence and contribution, while the 5th reviews the selection process.

Case A, the hearing held in Scotland, could initially be consider inclusive. Like the other hearings, six weeks’ notice was given (which is the recommended notice in the UK but can range from as little as 5–10 days’ notice in municipal hearings in Canada and the US) and the local media reported on the fact the hearing was taking place—largely because the development was controversial. The meeting was accessible to the local people who would be affected by the process. Hearing presentations had to be submitted in advance which clearly limits the spontaneity of discussion and the reflexivity of natural interaction. In terms of contribution (column 6) a fixed time slot and a presentation style of speaking is not strictly inclusive, which is why it has been given a medium score for contribution, but it can work to the advantage of the speaker where they are unlikely to be interrupted, meaning that people will be encouraged to listen to one another, which is an essential aspect of deliberation (Scudder 2020) and considered judgement. Potentially, hearings support participation for those that prefer to prepare a speech in advance.

For the hearing held in BC (B), more than one hearing was held, arguably facilitating better attendance and accessibility, and supporting higher levels of inclusiveness. Like case A, there was a real mix of attendees, including interest groups, advocacy organisations, political parties, trade unions, academics, members of the citizens’ assembly, the public (Fung & Warren 2010: 59) and elected government officials (Lang 2007: 40). The opportunity for a range of stakeholders to speak in one process lends a distinctive attribute to the hearing (Abels 2007: 109). Meinig (1998) believes that this leads to diversified participation, including thought-provoking evidence and discussion that results in effective compromise. Both A and B used a self-selecting recruitment process, which is typical for most public hearings.

The regional (C) and supranational (D) hearings were not advertised widely. While this was deliberate, this was unnecessary for hearing C—it could have been accessible to a more varied populace which may have brought wider perspectives. In terms of presence, participants had to apply to be involved and the UN hearing (D) was ‘invite only’, thus limiting the variety of voices that could be heard, which is why they have received a lower score than the other hearings. Yet in hearing D, every person that attended contributed to proceedings. They were able to prepare and had time to talk without interruption. However, accessibility and the range of participants was not as high as the other hearings.

What can be seen from Table 2 is that overwhelmingly, the cases scored well for inclusiveness in this context. What resulted from the self-selecting processes was a wide range of groups in attendance but essentially a different demographic than processes using random sampling—interest groups, political officials, experts, lay citizens, community organisations, NGOs, business groups, media, social commentators all in one room. Crucially, this is not something that deliberative mini-publics tend to facilitate meaning that hearings can bring a different form of evidence and information to the democratic process.

The key message here is that this inclusiveness appeared able to span levels of governance and despite the various formats—chair, number of hearings held, quasi-judicial or legislative—most hearings (apart from case D which was never designed to be inclusive) fared well. Yet, there is no real understanding of who takes part in a hearing with no record of gender, age, ethnicity or socio-economic position, which poses some challenges for analysing how inclusive hearings are.

Popular control

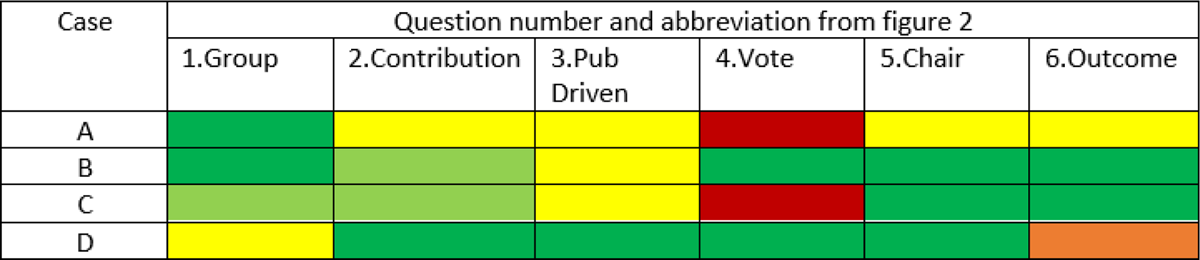

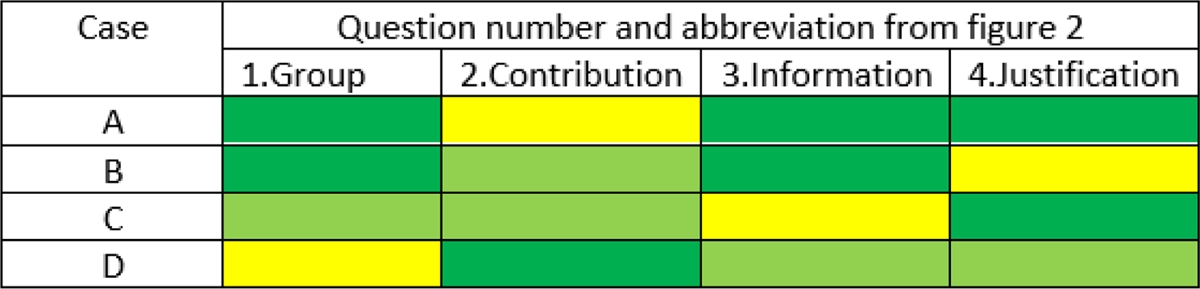

Table 3 shows that popular control is thus measured through the diversity of attendees (q.4 – see Figures 2 and 3), and the impact the public had on the agenda (q.7), the debate (q.6), and the outcome (q.8 and q.11). The role of chair is also paramount to ensure fairness and that no individual or group dominates proceedings (q.9).

As discussed above, it could be considered that all the cases had a diverse mix of attendees, although the UN hearing did not have the same range as others. All hearings scored medium to high for all participants contributing to the discussion (column 2). This is important because a range of stakeholders having control of the process means that it is less likely to be dominated by one group (see Figures 2 and 3 for details).

The Scottish case (A) fared less well for popular control. It was held in accordance with planning policy. It was chaired by an organised task force appointed by the government, which was expected to hold the inquisitorial process, the hearing and write the necessary recommendations, and was therefore viewed to be less neutral than the other chairs (Lightbody 2016: 135). The outcome of this hearing was limited to ‘yes or no’ to the development, so there was little room to propose alternatives or negotiate about the outcome meaning the community had little control over the outcome.

Hearing B’s chairs were members of the citizens’ assemblies, who were assumed to be neutral to the outcome of the process given they had no particular stake in the outcome. This hearing differed from A in that the chairs held a vote to gauge the opinions of participants. Although voting is not required in hearings, in terms of legitimising and highlighting discrepancies, voting could be a vital indicator of the feeling in the room and if any agreement has been met. If participants have no control over the final outcome of a hearing, it can be questioned why they are there at all. The outcome of B’s hearing had higher levels of popular control than A. Participants were restricted to discussing electoral change, but a range of electoral systems were up for discussion (Ratner 2005: 24). The recommendations of the hearings were not upheld by the CA members (the CA recommended the STV electoral system rather than MMP), which may indicate that CA members did not listen to hearing participants yet the process itself opened the discussion to more perspectives and input.

Case C, like B (column 5), received high measures of popular control for having neutral chairs, and because the outcome had not been decided prior to the process. The hearing was driven by a Task Force which was set up by the EC. Due to the driving force behind this organisation, it is considered fair to count it as a political body, it was therefore given a medium score (Lightbody 2016: 136). This was more of a ‘problem solving’ process rather than a policy shaping agenda. Therefore, no votes were taken at the end but the opinions were undoubtedly taken into consideration and acknowledged in the final report. The EC hearing was not designed to have an outcome due to it being an information sharing and knowledge exchange exercise.

As the public were a driving force in helping to set the agenda in case D there was a degree of popular control (D3). Being able to call for a process which enables local people to be heard—whether in their own community or at the UN level - gives power and control to citizens who, all too often, are not heard by their representatives. This finding is supported by Karpowitz and Mansbridge’s (2005: 352) case study which found that the hearing participants felt that they were able to directly influence decision makers with their arguments. The hearing concluded in a recommendation to amend UK policy on freedom of information. Although recommendations made by the Aarhus Committee have been upheld in the past, a recommendation is not the same as being able to implement change, the impact is therefore arguably low.

Interestingly here there is a variance regarding which hearings did well. B was linked with other democratic processes (citizens’ assembly and a referendum) so the popular control was not centred around the hearings. The hearings instead brought a wider level of inclusion to the other processes. While public hearings can be seen as a ‘top-down’ process (Warren 2009), there is scope for them to be citizen-initiated processes (Bherer et al. 2021). The supranational hearing (D) had a reasonable level of popular control which is consistent with the fact that the public called for it, set the agenda and it ruled on the lack of popular control which had been witnessed on a local/national issue. Therefore, as a tool to review decisions and as part of a wider participatory process, or a system, hearings fare well. More specifically, it can result in policy or planning decisions or amendments, albeit on a narrow agenda (hearing A), public hearings can feasibly link collective deliberation with decision making.

Transparency

Figure 2 shows that transparency is measured through the neutrality of the chairperson (q.9), the information available which would allow people to contribute appropriately (q.1, 10) and that the outcome had not yet been decided (q.11 – see Table 4).

It is worth noting that there is a lack of transparency which surrounds public hearings for the average citizen. Documents, records, and minutes are hard to come by and there are no specific rules regarding the hearing materials and how they are made available to the wider public (Mikuli & Kuca 2016: 15). Having said that, hearings can be transparent as cases A and B(1) show. They were widely publicised and used digital innovations to disseminate information as well as other means (radio, newspapers, websites, online forums). The framework for transparency has highlighted that the hearings held at the top level of governance (C1 and D1) were not as transparent as the local/regional hearings. The distribution of the necessary information, not just to those that participate in the process but more widely, is indicative of the far-reaching capacity of a hearing. Only then can people make an informed decision as to whether they should attend the process and feel that they know what is happening in their area or on a certain issue which may affect them.

The Scottish hearing was publicised early and widely (A). The controversy of building a windfarm in the Highlands was such that the opposition organised themselves extremely effectively and quickly, accommodated by the coverage from the local press. The organisers of the hearing ensured that all information and necessary documentation was in the library, as well as being available at the sessions (Rice 2014: 174). Furthermore, all the documents were available on the Scottish Government’s website for the necessary 12-week post-decision rule. The BC public hearings (B) were particularly transparent. The process was advertised early meaning that people were more likely, or more able, to attend. There was much discussion surrounding the event due to the uniqueness of its connection to the CA. The media, social networks and organisational group made efforts to keep the public informed (Fung et al. 2010: 61). Further to this, the hearings had neutral Chairs and the outcome was not pre-determined meaning that the process was open and transparent.

The EC hearing was not as transparent (C). The participants were clear about why they were there and what they would bring to the hearing meaning that the process was open, contributing to its ability to offer a transparent process and yet, the wider public was not privy to information about the process. As an information gathering and roundtable discussion to try and develop ideas for improving European Manufacturing it is understandable that this may not be of interest to everybody. The UN process (D) was transparent in certain aspects but the lack of documentation, recordings or minutes on what was discussed is highly problematic. While understandably narrowing those that were in attendance to ensure a focused and fair process, this limits the larger impact the Committee has to offer as many more could know about the system and how it works to protect members of the public. Referring contested decisions made by national government to an otherwise neutral third party, enables the UN to make use of its role as a supranational adjudicator, making it an effective tool in legitimising decisions. Although it was covered on the national news and programmes such as BBC programme Newsnight, more could have been done to publicise this type of event.

Overall, most of the hearings fared well in terms of transparency but were nevertheless unable to score high over all criteria. Again, hearing B has scored high, highlighting that this networked or sequenced approach is maybe where hearings are best placed.

Considered judgement

The final democratic norm to be considered is ‘considered judgement’. The quality of interaction and discussion will, in many respects, rely on the quality of the information available to the wider public before, during and after the process. Through collective and public debate, a variety of perspectives are highlighted and discussed, measured through the diversity of opinions offered (Figure 2 q.4 and 6). Necessary information is also available so that participants can contribute effectively (q. 10). The final measurement is the justification offered by the speakers (q.12).

The hearing on a windfarm development (A) (column 1, Table 5) was attended by many interest groups and associations. There is an argument to tread cautiously here due to the ability of interest groups to drown out other voices, and yet it scored high for other aspects—good range of contributions, and high for information and justifications. This public hearing held rigidly to the evidence-giving, quasi-judicial procedure meaning the contribution was not as flexible as it could have been in a more natural or informal setting. It is possible that associations work better in this type of hearing, indicating that experienced presenters or mobilised strategy is more effectual than an individual in this setting. Yet, there were quite a few individuals speaking for themselves too (Lightbody 2016: 151–2), and this mix of speakers is something that the hearing can bring to the deliberative democratic system.

All hearings scored medium-high for facilitating contributions from a wide range of participants, yet that does not include time to respond or engage in dialogue, limiting the scope and impact of the hearing (Johnston et al. 2013). While a wide variety of perspectives were heard, how deeply they were explored is dependent on how well-prepared participants were. Information for hearing A and B was easily accessible, meaning that non-participants were kept informed of proceedings and those participating had the opportunity to access information that could help them to prepare and respond which was made available in the local library (case A) and online (case B) (Lightbody 2016).

All of the hearings scored medium-high for the speech acts delivered within the proceedings. Those that spoke had put time and effort into their presentations, providing evidence and sources to support their main points. This finding again is supported by the literature: hearings generate sophisticated arguments where participants offer multiple justifications for their standpoints, which they attribute to the chance to prepare statements rather than speaking freely and responding to information and other participants (Steffensmeier et al. 2008: 11). Only one hearing received a medium level of membership for justification and this was the BC hearing. The reason it was awarded a lower score for justification is the quality of conversation was not perceived by the CA members to be of a high quality as many participants did not offer reasons for their standpoints (Ratner 2005: 26; Lang 2007: 45–6).

Largely though, the hearings have done well for considered judgement supporting Karpowitz and Mansbridge (2005), and others, findings in their studies as discussed earlier. High levels of sophisticated justification for points of view, a diverse group of attendees and wide contributions meant that many perspectives were aired. This may not embody the ‘ideal’ speech acts that Habermas (1984) imagined but there is undoubtedly a degree of deliberation taking place in public hearings. The next section draws out the main findings and considers what this means for hearings in a deliberative context.

Discussion and conclusions

Limitations of this study need to be acknowledged. The hearings have been chosen specifically for the different features they represent. With four case studies, it is challenging to provide both the richness that comes with a single case study but the generalisable benefit of many cases. There is much to suggest that hearings can be tokenistic or can be poorly utilised. Yet, the research here contributes to this field of research in an important way. The democratic norms have been consistently fulfilled by the hearings shown here. Their adaptable features and formal procedure are an intrinsic part of this. Hearings can embody both legislative or quasi-judicial characteristics; they can be held from the local to the supranational governmental level; they can be used for information gathering, information giving, problem solving, adjudicating or a collaborative decision-making process; and finally, they can be a place for citizens, experts, associations and governmental representatives to listen, learn, appease, rage or debate with one another. While their different features do not lead to substantially different outcomes in the ability to fulfil the democratic norms, it is evident that if they are successfully coupled with a deliberative process it does seem to result in them embodying the democratic goods more effectively.

Hearings in this research have shown that they can set the agenda and highlight issues that are of interest to citizens. They have been used to make decisions and review the legitimacy or legality of decisions made elsewhere; highlighting the flexibility of their use at different points of the policy-making process. By spanning levels of governance and embodying different features, public hearings have also been shown to effectively scale up participation at different levels of governance. As part of their use, hearings are already part of a representative democratic policy-making process (supranational, national, regional, devolved governments, and local councils) but these hearings’ evidence that they can successfully be coupled with deliberative (citizens’ assemblies) and direct processes (referendums) too which can potentially further support the institutionalisation of deliberative processes into policy and decision-making. In addition, it could go some way to further legitimise outcomes of processes, such as citizens’ assemblies or participatory budgeting, by including a wider populace and providing transparency to the broader process.

Further to this, hearings have the potential to contribute to the inclusivity and popular control of a deliberative process which recruits using sortition, by bringing in a different demographic through self-selection. A demographic no less deserving of a voice and a way to get involved. While the degree of considered judgement is high here for the four case studies, it is acknowledged that this fields a different type of communication than a mini-public. It can potentially be more agonistic, more confrontational, but no less needed. The hearings included in this article have supported the literature in finding that the calibre of input can be very high in a hearing—thought-provoking and well evidenced. Giving people an additional entry point to accessing policy makers and adding a layer of scrutiny is a positive aspect to making policy decisions transparent and include a wider demographic.

There is cause to be cautious however, as McComas et al. (2010: 124–5) highlights, public hearings might take the place of more innovative, citizen centred processes, and if used improperly, they may be used to legitimise the dominant political paradigm (127). Hearings are, for the most part, top down processes which can be subject to manipulation and applied tokenistically to placate the public (Lightbody 2016: 215). The outcome of hearings can even be ignored by political actors (98). However, this research shows that there is potential for public hearings to host the democratic standards thus showing that they could benefit the deliberative democratic process. With such a variety of uses and procedures, there is scope to adopt hearings as a part of a deliberative democratic system. The DSEI has allowed this research to hone in on some vital attributes from the case studies and highlight where hearings are stronger and weaker. This framework will enable other researchers to replicate this study on hearings and other democratic processes, allowing for future comparative work.

Notes

- The author has a copy of all documentation listed here and is able to provide access to readers if required. ⮭

- More information on how the framework was designed and executed, and detailed explanations of the measurements can be found in Lightbody 2016, chapter 6 and 7. ⮭

Supplementary File

DSEI Measurement Criteria for Questions in Figure 2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.1454.s14

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Professors Stephen Elstub and John Connolly for reading early drafts of this article. And to the anonymous reviewers for their kind and constructive feedback.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

1 Abels, G. (2007). Citizen involvement in public policy-making, Does it improve democratic legitimacy and accountability? The case of pTA. Interdisciplinary Information Sciences, 13, 1, 103–116. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4036/iis.2007.103

2 Arendt, H. (1968). Between past and future, eight exercises in political thought. Viking Press.

3 Bächtiger, A., & Parkinson, J. (2019). Mapping and measuring deliberation: Towards a new deliberative quality. Oxford online edn, Oxford Academic. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199672196.001.0001

4 Baker, W. H., Addams, H. L., & Davis, B. (2005). Critical factors for enhancing municipal public hearings. Public Administration Review, 65(4), 490–499. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2005.00474.x

5 Bherer, L., Gauthier, M., & Simard, L. (2021). Developing the public participation field: The role of independent bodies for public participation. Administration & Society, 53(5), 680–707. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0095399720957606

6 Boswell, J., & Corbett, J. (2021). Democracy, interpretation, and the “problem” of conceptual ambiguity: Reflections on the V-Dem Project’s struggles with operationalizing deliberative democracy. Polity, 53(2), 239–263. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1086/713173

7 Boswell, J., Dean, R., & Smith, G. (2023). Integrating citizen deliberation into climate governance: Lessons on robust design from six climate assemblies. Public Administration, 101(1), 182–200. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12883

8 Catt, H., & Murphy, M. (2003) ‘What voice for the people? Categorising methods of public consultation’. Australian Journal of Political Science, 26, 549–67. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/1036114032000133967

9 Cohen, J. (1997). Deliberation and democratic legitimacy. In J. Bohman and W. Rehg (eds), Deliberative democracy (pp. 67–91). Cambridge MA: MIT Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0006

10 Deligiaouri, A., & Suiter, J. (2021). A policy impact tool: Measuring the policy impact of public participation in deliberative e-rulemaking. Policy Internet, 13, 349–365. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.254

11 Demski, C., & Capstick, S. (2022). Impact evaluation framework for climate assemblies, KNOCA. Available at: https://knoca.eu/app/uploads/2022/11/Impact-evaluation-framework-for-climate-assemblies-1.pdf

12 Dryzek, J. S. (1990). Discursive democracy: Politics, policy and political science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/9781139173810

13 Dryzek, J. S. (2005). The politics of the earth, environmental discourses. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

14 Elstub, S. (2014). Deliberative pragmatic equilibrium review: A framework for comparing institutional devices their enactment of deliberative democracy in the UK. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 16(3), 386–409. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-856X.12000

15 Elstub, S., & Escobar, O. (eds) (2019). The handbook of democratic innovation & governance. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4337/9781786433862

16 Femia, J. (1996). Complexity and deliberative democracy. Inquiry, 39, 361–97. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/00201749608602427

17 Fishkin, J. S. (2009). When the people speak, deliberative democracy and public consultation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

18 Fournier, P., van der Kolk, H., Carty, R. K., Blais, A., & Rose, J. (2011). When citizens decide: Lessons from citizen Assemblies on Electoral Reform (Oxford: OUP). DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199567843.001.0001

19 Fung, A. (2006). Varieties of participation in complex governance. Public Administration Review, 66, 66–75. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4096571. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00667.x

20 Fung, A., Warren, M., & Gabriel, O. W. (2010). The British Columbia Citizens’ Assembly on electoral reform (BCCA). ‘Participedia’ [online]. Available at: www.participedia.net.

21 Gastil J., & Black L. (2007). Public deliberation as the organizing principle of political communication research. Journal of Public Deliberation, 4(1). DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.59

22 Goodin, R. E. (2005). Sequencing deliberative moments. Acta Politica, 40, 182–96. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500098

23 Habermas, J. (1984). The theory of communicative action. Vol. I: Reason and the rationalization of society, T. McCarthy (trans.). Boston: Beacon.

24 Hendriks, C. M. (2016). Coupling citizens and elites in deliberative systems: The role of institutional design. European Journal of Political Research, 55, 43–60. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12123

25 Hendriks, C. M. (2011). The politics of public deliberation: Citizen engagement and interest advocacy. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1057/9780230347564

26 Johnston, R., Pattie, C., & Rossiter, D. (2013). Local inquiries or public hearings: Changes In public consultation over the redistribution of UK parliamentary constituency boundaries. Public Admin, 91, 663–679. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12020

27 Innes, J. E., & Booher, D. E. (2004). Reframing public participation: Strategies for the 21st century. Planning Theory and Practice, 5(4), 419–436. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/1464935042000293170

28 Karpowitz, C. F., & Mansbridge, J. (2005). Disagreement and consensus, the importance of dynamic updating in public deliberation. In Gastil, J. and Levine, P. (eds), The deliberative democracy handbook, strategies for effective civic engagement in the 21st century (pp. 237–253). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

29 Kemp, R. (1985). Planning, public hearings and the politics of discourse. In J. Forester (ed). Critical Theory and Public Life. MIT Press: USA.

30 King, C. S., Feltey, K. M., & O’Neill Susel, B. (1998). The question of public participation in public administration. Public Administration Review, 58(4), 317–26. https://www.jstor.org/stable/977561. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/977561

31 Klinke, A. (2009). Deliberative transnationalism — Transnational governance, public participation and expert deliberation. Forest Policy and Economics, 11, 348–356. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2009.02.001

32 Knight, J., & Johnson, J. (1997). What sort of equality does deliberative democracy require? in J. Bohman. and W. Rehg (eds), Essays on Reason and Politics: Deliberative Democracy. London: The MIT Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0013

33 Knobloch, K. R., Gastil, J., Reedy, J., & Cramer Walsh, K. (2013). Did they deliberate? Applying an evaluative model of democratic deliberation to the Oregon citizens’ initiative review. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 41(2), 105–125. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2012.760746

34 Lando, T. (2003). The public hearing process: A tool for citizen participation, or a path toward citizen alienation? National Civic Review, 92(1), 73–82. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/ncr.7

35 Lang, A. (2007). But is it for real? The British Columbia Citizens’ Assembly as a model of state-sponsored citizen empowerment. Politics and Society, 35(1), 35–69. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0032329206297147

36 Lightbody, R. (2016). Institutionalising deliberative democracy to promote environmental policy-making: The role of public hearings, Doctoral Thesis, University of the West of Scotland. Available at: https://researchonline.gcu.ac.uk/en/publications/institutionalising-deliberative-democracy-to-promote-environmenta

37 Mansbridge, J., Bohman, J., Chambers, S., Estlund, D., Føllesdal, A., Fung, A., Lafont, C., Manin, B., & Martí, J. l. (2010). The place of self-interest and the role of power in deliberative democracy. Journal of Political Philosophy, 18, 64–100. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9760.2009.00344.x

38 McComas, K., Besley, J. C., & Black, L. W. (2010). The rituals of public meetings. Public Administration Review, 70, 122–130. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2009.02116.x

39 Meinig, B. (1998). Public hearings: When and how to hold them. Municipal Research and Services Centre of Washington. [online] Available at: https://mrsc.org/explore-topics/governance/meetings/public-hearings

40 Michels, A., & Binnema, H. (2019). Assessing the impact of deliberative democratic initiatives at the local level: A framework for analysis. Administration & Society, 51(5), 749–769. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0095399718760588

41 Mikuli, P., & Kuca, G. (2016). The public hearing and law-making procedures. Liverpool Law Rev 37, 1–17. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s10991-016-9177-z

42 Ratner, R. S. (2005). The BC Citizens’ Assembly: The public hearings and deliberations stage. Canadian Parliamentary Review. Spring. 24–33. http://revparl.ca/28/1/28n1_05e_Ratner.pdf

43 Rice, K. (2014). Glenmorie Windfarm Report. Report to Scottish Ministers. Available at: http://www.dpea.scotland.gov.uk/CaseDetails.aspx?id=94331

44 Ryan, M., & Smith, G. (2012). Towards a comparative analysis of democratic innovations: Lessons from a small-N fs-QCA of participatory budgeting’. Revista Internacional de Sociologia, 70(2), 89–120. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3989/ris.2012.01.28

45 Schylter, P., & Stjernquist, I. (2010). Regulatory challenges and forest governance in Sweden. In K. Backstrand, J. Khan, A. Kronsell, & E. Lovbrand (eds), Environmental politics and deliberative democracy: Examining the promise of new modes of governance. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4337/9781849806411.00020

46 Scudder, M. (2020). Beyond empathy and inclusion: The challenge of listening in democratic deliberation. Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197535455.001.0001

47 Smith, G. (2009). Democratic innovations: Designing institutions for citizen participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511609848

48 Spada, P., & Ryan, M. (2017). The failure to examine failures in democratic innovation. PS: Political Science & Politics, 50(3), 772–778. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096517000579

49 Steffensmeier, T., Schenck-Hamlin, W., & Procter, D. (2008). Developing deliberative practice, argument quality in public deliberations. A Kettering Foundation Report. Available at: https://www.kettering.org/sites/default/files/product-downloads/CFPL_KF_KANSAS_LR.pdf. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/00028533.2008.11821693

50 Steiner, J. (2012). The foundations of deliberative democracy, empirical research and normative implications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139057486

51 Warren, M. E. (2007). Institutionalising deliberative democracy. In S. Rosenberg (ed). Can the people govern? Deliberation, participation and democracy (pp. 272–88). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1057/9780230591080_13

52 Warren, M. E. (2009). Governance-driven democratization. Critical Policy Studies, 3(1), 3–13. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/19460170903158040

53 Wraith, R. E., & Lamb, G. B. (1971). Public inquiries as an instrument of government. Oxford: George Allen and Unwin Ltd.

54 Young, I. M. (2000). Inclusion and democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.