1. Introduction

Democratic theory’s deliberative turn has spurred an intense debate about the merits of ‘talk-centered’ (Steiner 2012: 37) democratic processes. Deliberative democracy is advocated less as an end in itself than by dint of its presumed instrumental value for beneficial purposes. It is expected to give rise to two achievements: ‘better policies’ and ‘better citizens’ (Jacquet & van der Does 2020; Pincock 2012; Steiner 2012). Our paper aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of the latter: the assumption that deliberative democracy’s core practice of political discussion exerts a powerful ‘self-transformative’ effect on its participants that renders them in several ways better suited and more capable for democratic politics (Mansbridge 1999; Warren 1992). A sizable body of research has examined ‘educative effects’ of political discussion for the quality of public opinion (Pincock 2012: 144–148). We focus on another, much less developed strand of reasoning on ‘better citizens’. It revolves around democratic legitimacy.

As presumably ideal procedures for democratic decision-making, discussion-centric processes are expected to generate legitimacy for public policies as well as the political system at large (Cohen 1989; Habermas 1996). Accordingly, people’s involvement in political discussions has been claimed to nurture democratic orientations like identification with one’s political community, trust in the political system, external efficacy, tolerance for pluralism and diversity, and active participation in public life (Mutz 2008: 530; Pincock 2012: 148–149; Steiner 2012: 222).

Theoretically and empirically, however, this line of scholarship is rather vaguely demarcated and not very stringently structured. This observation applies to both sides of the equation: the conceptualization of citizens’ political communication with one another as explanans, as well as citizens’ democratic orientations as explanandum. Research on ordinary people’s political talk has progressed in two, mostly segregated trajectories, one focusing on casual conversations about public affairs among citizens in their everyday lives (Conover & Miller 2018), the other on formalized discussions in deliberative forums (Bächtiger 2016). With regard to its presumed consequences, research resembles a ‘shopping list’ (Kuyper 2018: 3) of democratically desirable attitudes and behaviors rather than a conceptually integrated, coherent, and systematic body of work. The existing evidence is eclectic, patchy, and sometimes also contradictory. Against this backdrop, we aim to assess how political talk, in all its various guises, affects the wide range of orientations that together constitute democratic citizenship.

To alleviate the deficiencies of extant research, our study provides a holistic tableau of evidence that is more systematic, broader in scope, and therefore more complete with regard to citizens’ political talk on the one hand, and the democratic orientations presumably affected by its various manifestations on the other. Our findings thus provide a comprehensive birds’ eye perspective on the multi-faceted relationship between political talk and democratic citizenship:

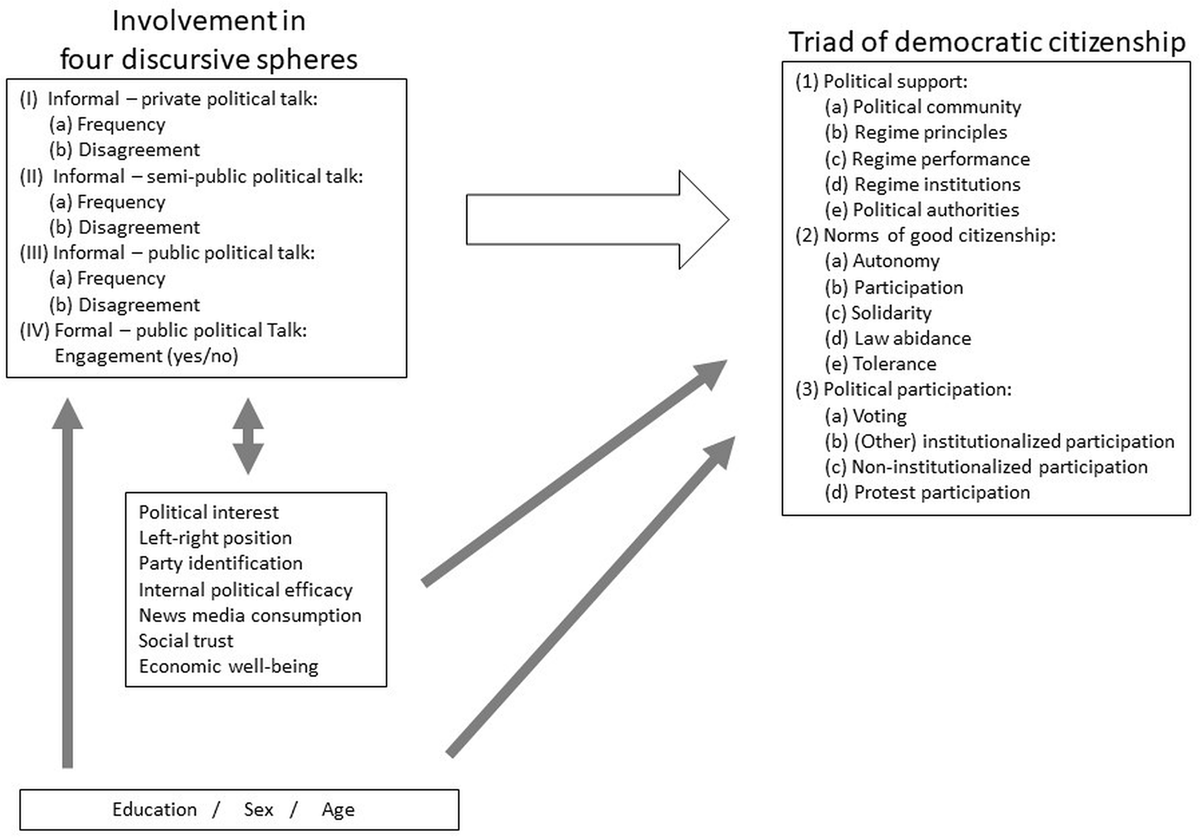

To overcome the compartmentalization of perspectives on political talk, we conceptualize citizens’ involvement in this activity as a system of four distinct ‘discursive spheres’ (Hendriks 2006) that range from informal private conversations over semi-public and public, but still informal, exchanges, to formalized public discussions at organized events (Schmitt-Beck & Grill 2020). We focus on two crucial aspects of citizens’ involvement in political talk: their engagement in the respective discursive spheres—whether and how often they discuss politics in these arenas; and their encounters with disagreement—how often they experience opinion differences during these conversations (Nir 2017).

We conceptualize citizens’ orientations toward democracy as a political order, and their own roles within it, in terms of a triad of democratic citizenship that encompasses three pillars: citizens’ attitudes about the democratic political system and its elements, their norms of good citizenship, and their participation in different forms of political activity (Pattie et al. 2004; van Deth et al. 2007).

We begin with a detailed outline of this conceptional groundwork, from which we then develop testable hypotheses. Our empirical contribution is based on two complementary high-quality surveys from Germany: the 2017/18 CoDem survey and the 2018 German General Social Survey ALLBUS. Our analyses find marked positive associations of conversations within family and friendship circles as well as discussions at organized events with democratic citizenship but only for political participation they allow to attribute these associations to the assumed ‘self-transformative’ effect of political talk. Strikingly, engagement in the public discursive sphere of casual conversations with strangers weakens rather than strengthens people’s support for the democratic system, citizenship norms, and likelihood of electoral participation. Disagreement experiences are often inconsequential, but whenever they appear relevant, their role is beneficial.

2. Four Discursive Spheres of Citizens’ Political Talk

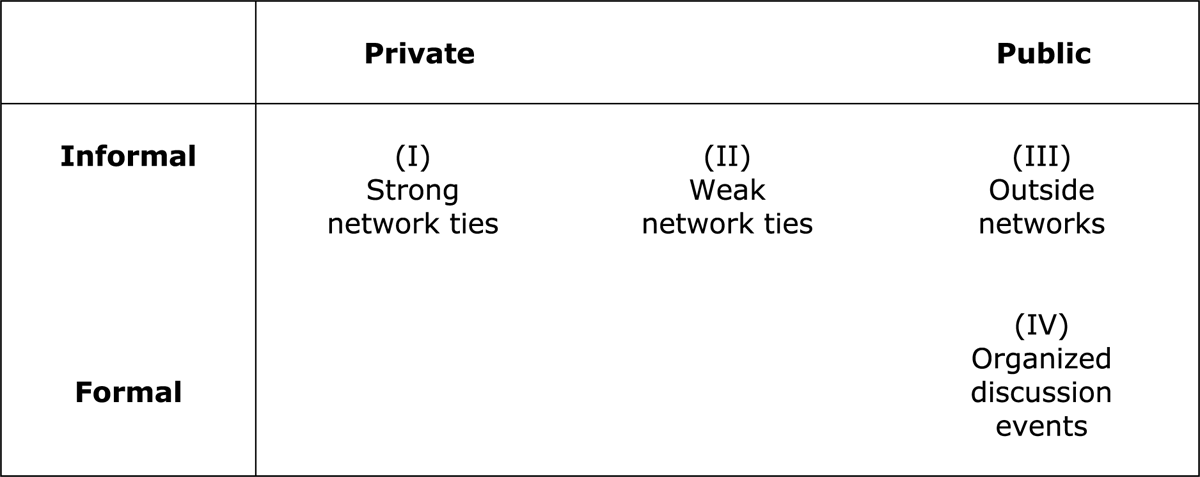

To represent the various modalities of citizens’ political talk in an integrated analytical framework, we draw on a typology that conceives this phenomenon as a sub-system of the overall deliberative system (Neblo 2015: 17–25) that is differentiated into four distinct ‘discursive spheres’ (Hendriks 2006). It is derived from two dimensions of political talk that are accorded prominent roles in theorizing on deliberative democracy (Figure 1): the amount of its privacy or publicity (Stevenson & Dryzek 2014: 27–28; Weintraub 1997), and whether it occurs informally in people’s everyday lifeworld or in a formalized fashion within organized settings (Fleuß et al. 2018; Richards & Neblo 2022; Schudson 1997). Conceptual tools for fine-tuning this typology are gleaned from research on citizens’ social networks (Huckfeldt & Sprague 1995) and symbolic interactionism (Goffman 1963).

Three of these discursive spheres concern informal everyday political talk, the casual, non-purposive, unstructured, spontaneous, and free-flowing conversations about public affairs occurring in day-to-day situations (Conover & Miller 2018). The first discursive sphere (I) is established through conversations within people’s core networks (Marsden 1987). They involve persons attached through the dense, emotionally charged, highly valued ‘strong ties’ of kinship and friendship (Straits 1991), and take place in protected spaces, most notably people’s homes. Their character is thus private.

The second discursive sphere (II) involves conversations within the ‘weak ties’ (Granovetter 1973) that connect mere acquaintances (Goffman 1963: 112–123), such as co-workers or neighbors. Access to these conversations is regulated by norms of politeness and etiquette rather than physical and legal barriers (Goffman 1963: 151–165). The character of these conversations is best characterized as semi-public, as they straddle the divide between individuals’ private lifeworld and the public sphere.

The third discursive sphere (III) is constituted by everyday political talk between strangers. Taking place outside people’s social networks and in completely open settings where access cannot be controlled, its character is unequivocally public (Goffman 1963: 124–148). Railroad compartments are archetypical contexts for such episodic communications between unacquainted persons that share nothing except their accidental simultaneous presence in the same space at the same time (Noelle-Neumann 1974). According to theorists of the public sphere, it is primarily in this arena, rather than within the confines of strong or even weak network ties, that society at large engages in a conversation with itself (Habermas 1989: 31–43; Hauser 1999).

The fourth discursive sphere (IV) is also public and likewise involves communication between strangers. But its setting are organized discussion events, rendering its character formal. This kind of political talk is instrumental (Schudson 1997). It is thematically focused, typically on a topical issue of public policy on which participants’ perspectives are invited by some organizing agency. And it takes place at a fixed time in a structured format that is defined by set communication rules. For deliberative democrats, deliberative minipublics stand out as a particularly valuable type of such events (Elstub 2014). But conventional, and less explicitly rule-guided forms like town hall meetings, public hearings, or campaign assemblies are much more common, and therefore personally experienced by considerably larger numbers of citizens.

3. The Triad of Democratic Citizenship

In modern democracies, the notion of citizenship refers to an individual’s membership in a polity and the associated rights and responsibilities (Marshall 1950). It is defined by a vertical relationship with the institutions of the state, and a horizontal relationship to fellow citizens. Research on democratic citizenship starts from the premise that beyond the formal granting of citizenship rights, what matters for the functioning of democratic systems is how people understand and live up to their roles as citizens of a democracy, how loyal they feel toward the democratic political order, and to what extent they are willing to take over the rights and responsibilities that come with the legal status bestowed on them.

As an integrated research agenda, the study of democratic citizenship combines two classical fields of political science: political culture, broadly speaking research about citizens’ orientations toward the democratic political system of which they are members, including views concerning this membership itself (Almond & Verba 1963; Dalton 2008; Easton 1975), and political participation, the study of how and why citizens actively engage in this system’s political process (van Deth 2003; Verba et al. 1995). Recent studies have converged on a comprehensive framework that can be characterized as a triad of citizenship—a three-pronged conceptualization according to which democratic citizenship encompasses (1) an attitudinal dimension that concerns individuals’ orientations toward the democratic political system whose members they are, (2) a normative dimension of views about ‘good’ citizenship, and (3) a behavioral pillar pertaining to active participation in this system’s political process (Pattie et al. 2004; van Deth et al. 2007).

3.1 Attitudes

In the study of political culture, Easton’s (1975) notion of political support is widely accepted as the analytically most useful framework for conceptualizing orientations toward democratic political systems. It encapsulates citizens’ attitudes toward a wide variety of objects within the political system at large, based on the crucial distinction between the system levels of the political community, regime (subdivided between orientations toward the regime’s principles, performance, and institutions), and authorities (Norris 1999; Thomassen & van Ham 2017). Positive attitudes toward the political community and regime are particularly important for democratic systems to thrive (Easton 1975: 439).

Support for the political community refers to ‘a basic attachment to the nation beyond the present institutions of government and a general willingness to co-operate together politically’ among the citizens of a state (Norris 1999: 10). Support for democratic regime principles concerns citizens’ general, ‘diffuse’ preference for a democratic regime as such, as well as the subjective importance of specific core principles like pluralism, freedom of expression, and the critical role of media and the opposition, as emphasized by liberal democracy, and the relevance of political discussion, prioritized by deliberative democracy. Referring to the actual implementation of democracy, ‘specific’ support for the regime’s performance concerns citizens’ satisfaction with how their country’s democracy works in practice. Support for regime institutions refers to citizens’ confidence in the core institutions of this democratic system, such as parliaments, political parties, courts, or the public administration. Support for political authorities, finally, pertains to current office holders, most notably with regard to their responsiveness to citizens’ demands (Norris 1999; van Ham & Thomassen 2017).

3.2 Norms

The second pillar concerns citizens’ normative orientations regarding their own role in democracy—‘what people think people should do as good citizens’ (Dalton 2008: 78). For the viability of democratic systems, the norms and principles that govern citizens’ relationships with the institutions of the state and their fellow citizens (Denters et al. 2007: 90) matter because they determine which behaviors citizens are more or less likely to engage in, and for what reasons.

Extant research has identified four distinct facets of citizenship norms (Dalton 2008; van Deth 2007) that emanate from different conceptions of democracy, ranging from elitist over liberal, communitarian and participatory to deliberative understandings (Denters et al. 2007: 90–92). These competing views about the meaning and essence of democracy highlight different normatively desirable characteristics of a good citizen. From a deliberative democratic viewpoint citizens’ autonomy, participation, and solidarity appear especially important. The norm of autonomy envisions a good citizen as someone who is informed and knowledgeable but also critical about politics, while at the same time willing to reflect on her own opinions and to exchange different viewpoints with fellow citizens. The facet of participation conceives of the good citizen as a person who is actively engaged in public affairs and willing to participate in political and social activities. The norm of solidarity refers to views about desirable relationships between fellow citizens and emphasizes caring for those in need. The norm of law abidance, finally, refers to the acknowledgement of state legitimacy and the rule of law. If citizens were not loyal to the laws and regulations generated by democratic procedures, implementing democratic decisions would require force and coercion, and that would be diametrically opposed to the idea of self-governance through democratic deliberation (Schnaudt et al. 2021).

In addition, extant scholarship has highlighted tolerance as important element of good citizenship (Leite Viegas 2007). Defined as ‘willingness to put up with disagreeable ideas and groups in order to peacefully coexist’ (Sandoval-Hernández et al. 2021: 150), it envisions people who condone viewpoints they do not share, and who accept their advocates’ right to express them even when finding them objectionable. Lacking tolerance raises the risk of insurmountable political and societal conflict, thus posing a challenge to the viability of democratic systems.

3.3 Behavior

The behavioral dimension refers to people’s active engagement in democracy’s political process. ‘Political participation provides the mechanism by which citizens can communicate information about their interests, preferences, and needs and generate pressure to respond.’ (Verba et al. 1995: 1) Democracy cannot thrive if citizens are passive and apathetic; hence, a high level of participation is generally desirable from the perspective of democratic citizenship. In modern democracies citizens can draw on a multitude of ways to become politically active.

The most basic distinction refers to institutionalized and non-institutionalized modes of participation. Institutionalized participation concerns political activities that take place within the confines of the institutional process and are directly geared toward the political elites and authorities that govern this process. The archetype of institutionalized participation is voting. Other and less common examples of institutionalized participation include working for a political party and contacting politicians. Non-institutionalized participation pertains to political activities that take place outside the institutional pathways of representative democracy, such as signing petitions, boycotting, or partaking in citizen initiatives (van Deth 2003). Due to their overt elite-challenging character, protest activities, such as demonstrations or (online) protest campaigns, have been identified as yet another distinct form of (also non-institutionalized) participation (Oser 2022).

4. Political Talk and Democratic Citizenship: Hypotheses

Theorizing about deliberative democracy assumes that engagement in political talk leads to ‘better citizens’ in the sense of enhanced democratic citizenship in all three of its dimensions—attitudes, norms, and behaviors (Kuyper 2018). Correspondingly, our analysis starts with the baseline hypothesis that partaking in political discussions gives rise to stronger support for the democratic political system, more pronounced alignment with norms of good democratic citizenship, and a higher inclination to become active in politics (H1). While no study ever attempted to examine the effects of political talk on the triad of citizenship nor any of its pillars in full, some scattered findings are in line with this basic expectation. Aspects of political support, such as satisfaction with democracy, trust in political institutions, or external political efficacy, have been found to be positively related to political discussions in social networks (Searing et al. 2007), or deliberative minipublics (Myers & Mendelberg 2013). Searing et al. (2007) found social network conversations also being related to citizenship norms like law abidance and active engagement. Other research has detected mobilizing effects of social network communication on turnout, and occasionally also political participation more generally (Rolfe & Chan 2018).

At least two caveats can be raised against this straightforward hypothesis. First, it could be argued that beneficial implications of political talk presuppose effective influence of this practice on public policies (Mansbridge 1999). Due to its non-purposive character, no such consequences should accordingly derive from informal everyday political talk. Discussions in deliberative forums and other public events, by contrast, are organized to address pertinent policy problems (Schudson 1997). Conditions might thus be more favorable for the assumed beneficial effects in the discursive sphere of formal discussion events than the three discursive spheres of everyday political talk. This suggests the conditional hypothesis that beneficial consequences for democratic citizenship result from engagement in the discursive sphere of formal public discussion events (IV) but less so from engagement in the various modalities (I – III) of informal everyday political talk (H2.1). Since previous studies did not systematically compare different modes of political talk, so far no empirical findings on this hypothesis exist.

Complicating things further, qualitative and experimental studies of everyday political talk suggest that there might be something special about informal conversations between strangers. Relying on artificial settings where political matters are informally discussed between persons individually recruited for research purposes and therefore strangers to each other, these studies consistently found political talk to converge on a ‘vernacular of political disaffection’ (Stoker et al. 2016: 10; cf. Bøggild et al. 2021; Saunders & Klandermans 2020). According to Stoker et al. (2016), such negativism in political talk is a function of how its content is processed. Formalized discussions in public settings should activate ‘slow,’ topically driven, careful, and reflective processing, resulting in positive effects on democratic citizenship. Everyday political talk, by contrast, might be more strongly characterized by ‘fast,’ superficial processing of its content. And ‘[i]n fast thinking mode the very nature of politics—its conflicts, rhetoric and practices—tend to attract negative judgments’ (Stoker et al. 2016: 16). In conversations with strangers this tendency might be particularly pronounced. We accordingly hypothesize that engagement in the public discursive sphere of conversations with strangers (III) weakens democratic citizenship (H2.2).

Apart from engagement in political talk as such it may also matter whether individuals are confronted with disagreeable viewpoints when discussing politics (Nir 2017; Klofstad et al. 2013). Deliberative democracy is seen as ideal approach to deal with disagreements over political goals in constructive and legitimate ways. It therefore presupposes that the experience of society’s political diversity is part and parcel of citizens’ encounters with one another (Gutmann & Thompson 1996). Exposing participants to heterogeneous viewpoints is therefore integral to the design of deliberative forums. Accordingly, in the discursive sphere of formalized public discussions (IV), engagement and disagreement can be assumed to be inseparably intertwined.

In casual everyday conversations, by contrast, people can try to seek out agreeable communication partners and avoid disagreeable ones (Huckfeldt & Sprague 1995; Huckfeldt et al. 2004). Accordingly, in the three discursive spheres of everyday political talk (I–III) the effects of engagement and political heterogeneity are analytically distinguishable. Deliberative democrats tend to expect generally positive consequences arising from encounters with disagreement. We translate this into the generic assumption that experiencing disagreement during political conversations in the three discursive spheres of everyday political talk (I–III) leads to stronger support for the democratic political system, more pronounced alignment with democratic norms of good citizenship, and a higher inclination to become active in politics (H3). The available evidence is eclectic and ambiguous. Carlson et al. (2020: 71–95) found negative rather than positive associations of disagreement in social networks with political trust and efficacy. According to Mutz (2006), such experiences undermine people’s eagerness to become active in politics, while rendering them more tolerant.

5. Data, Measures, and Strategy of Analysis

5.1 Data

Our study relies on the CoDem survey of 2017/18,1 a unique two-wave panel study specially designed to examine German citizens’ political talk, and the 2018 German General Social Survey ALLBUS,2 the reference study of the German social sciences. Both surveys were conducted face-to-face and are based on random samples, one of them local (CoDem), the other national (ALLBUS). They entail very similar measures for individuals’ involvement in political talk and numerous partly identical, partly equivalent, and partly complementary measures for the wide range of orientations and behaviors that together constitute the triad of democratic citizenship, thus allowing for a complete mapping of all relevant facets concerning the nexus between political talk and democratic citizenship.3

5.2 Independent Variables

To register citizens’ engagement in everyday political talk, both surveys queried the frequency of respondents’ informal political discussions in their families, with friends, with acquaintances, and with people they did not know. Conversations within the strong ties of family and friendship circles (averaged across the two items) pertain to the first, private discursive sphere (I), talks between acquaintances to the second, semi-public discursive sphere (II), and talks with strangers to the third, public discursive sphere of everyday political talk (III).4 Additional items are used to register whether or not (coded 1 or 0) respondents engaged in the fourth discursive sphere of formalized public discussions (IV; CoDem: ‘Participate actively in discussions during public meetings’; ALLBUS: ‘Take part in public discussions at meetings’). For everyday political talk (I–III), both surveys also included measures of the amount of general disagreement (Klofstad et al. 2013) encountered during these discussions (again averaged for kin and friends).5 The Supplementary Materials document these measures’ distributions.

5.3 Dependent Variables

To fully represent the three pillars of democratic citizenship, we rely on 21 dependent variables across the two data sets of which 11 refer to its attitudinal, and five each to its normative and behavioral dimensions (see Supplementary Materials for exact operationalizations). Several of these variables can be analyzed with both data sets, using partly identical and partly equivalent operationalizations (Table 1). Wherever possible we draw on established, tried-and-tested measures to increase the compatibility and comparability of our study with extant research on political culture and participation (Norris 1999: 16–21; van Deth 2003). For the attitudinal dimension of democratic citizenship, we make use of established measures regularly employed in studies of political support (Dalton 2004; Norris 1999; Thomassen & van Ham 2017). Information on the normative underpinnings of democratic citizenship is available in the CoDem data only. To indicate views of what makes up a ‘good citizen’ we draw on an item battery encompassing the norms of autonomy, participation, solidarity, and law abidance (Dalton 2008; Schnaudt et al. 2021; van Deth 2007). To measure tolerance, we use a count variable indicating the number of potentially problematic groups that according to respondents should be allowed to express their views in public (Leite Viegas 2007). Concerning political participation, we again draw on both CoDem and ALLBUS data, and consider four types of participation that reflect citizens’ political action repertories in modern democracies: voting, institutionalized participation, non-institutionalized participation, and protest participation (Oser 2022; van Deth 2003).

Overview of dependent variables.

| CoDem | Allbus 2018 | |

|---|---|---|

| Political support | ||

| Political community | Attachment to Germany | Identification with Germany and its population |

| Diffuse support: democracy as generic regime principle | Importance of living in democratic country | Endorsement of democracy as idea |

| Diffuse Support: regime principles of liberal democracy |

|

(Rejection of) Populism (inverted scale) |

| Diffuse Support: regime principles of deliberative democracy | Importance of political discussion before elections | |

| Specific support of democracy | Satisfaction with democracy | Satisfaction with democracy |

| Trust in political institutions |

|

|

| Specific support in authorities | External efficacy (scale) | External efficacy (scale) |

| Norms | ||

| Good citizenship |

|

|

| Tolerance | Tolerance (count variable) | |

| Politial participation | ||

| Turnout intention |

|

Turnout recall (dummy variable) |

| Institutionalized participation | Taken part in institutionalized activity (dummy variable) | |

| Non-institutionalized participation | Taken part in non-institutionalized activity (dummy variable) | Taken part in non-institutionalized activity (dummy variable) |

| Protest participation | Taken part in protest activity (dummy variable) | Taken part in protest activity (dummy variable) |

5.4 Strategy of Analysis

Our models analyze how each of these dependent variables is affected by seven independent variables: the frequency of respondents’ engagement in the private (I), semi-public (II) and public discursive spheres of informal everyday political talk (III) as well as the extent of disagreement experienced during these conversations, and whether or not they engaged in the formal discursive sphere of organized public discussion events (IV).

To obtain a complete picture of the relevance of political talk for democratic citizenship, we run several models on each dependent variable (with all continuous variables normalized to range 0 to 1). Since the amount of disagreement encountered during informal political conversations can only meaningfully be elicited from respondents that engage in the respective discursive sphere, we proceed sequentially. For each dependent variable we begin with a model that includes all respondents but contains only the measures of engagement in the four discursive spheres (M1). In the next step, we estimate separate models for each discursive sphere of everyday political talk that exclude all respondents that never discuss politics in the respective arena (M2.I to M2.III). These models include the disagreement variables for the respective discursive spheres and display—for the sake of completeness—again the effects of the frequency of political talk (whose meaning is now different than in M1 because non-discussants are removed and disagreement is controlled for).

We run each of these models in two versions that together define a range within which the true effects of our independent variables are situated: a permissive one (P) that controls only for unequivocally exogenous demographic characteristics (education, sex, age), and a restrictive one (R) that additionally controls for the most important attitudinal and behavioral predictors of political support, citizenship norms, and political participation, as identified by extant research (e.g., Dalton 2004, 2008; Norris 1999; Verba et al. 1995). These include political interest, left-right self-placement, party identification, internal efficacy, news media consumption (newspapers, public and private TV news), social trust, and economic well-being (see Supplementary Materials for details of operationalizations). Figure 2 visualizes this strategy of research.

The pairs of estimates that result from this two-track procedure have two alternative meanings that are observationally equivalent. Which of them is the correct one depends on the status of the attitudinal control variables in the causal sequence preceding democratic citizenship. In the literature, variables like political interest, internal efficacy, or media use are often treated as predictors of political talk (Schmitt-Beck & Lup 2013). But sometimes they are also conceived as its outcomes (e.g., Atkin 1972; Morrell 2005; Torcal & Maldonado 2014). If these variables are a common cause of both political talk and democratic citizenship, the restrictive models deliver appropriate estimates whereas the permissive models overestimate the genuine impact of political talk. If the latter interpretation is correct, these variables succeed rather than precede political talk and may therefore mediate its impact on democratic citizenship. In that case the permissive models would capture the true relevance of political talk whereas the restrictive models would artificially depress its (visible) impact by depleting it from all indirect, mediated effects (Cinelli et al. 2022). Figure 2 accordingly visualizes both causal sequences. Which of them is the correct one cannot be disambiguated with our data. In this situation we opt for a conservative interpretation that places stronger emphasis on the restrictive models because it minimizes the risk of overstating the impact of political talk. It should be borne in mind, however, that the true values might nonetheless be closer to those resulting from the permissive models.

6. Findings

6.1 Engagement in Political Talk

Political support: According to the permissive models in Table 2a, 6 most facets of political support are positively associated with everyday political talk within strong ties (I). However, although sometimes quite sizable, none of these effects persist in the restrictive models. A roughly similar pattern, though with rather small effect sizes, emerges for engagement in public discussion events (IV). Notably, its effects on diffuse support for democracy in general and pluralist liberal democracy in particular persist in the restrictive models. For conversations within weak ties (II) inconsistent findings emerge. We see few positive effects, and their sizes are small. However, unlike political talk within strong ties and at public discussion events, they appear equally strong under permissive and restrictive model specifications. Discussing politics with acquaintances appears to contribute somewhat more strongly to diffuse support for democracy in general as well as the liberal democratic assignment of a critical role to the opposition and the media. However, we also see negative effects. More frequent conversations of this type appear to strengthen populist attitudes (though only when controlling for disagreement), and to weaken individuals’ confidence in the institutions of representative government as well as their external efficacy (ALLBUS). By comparison, everyday political talk with strangers (III) appears much more influential, and its impact is overall negative. Again, this mostly holds in similar ways for permissive and restrictive models. Those engaging more frequently in the discursive sphere of informal public political talk tend to display less diffuse support for the political community and the regime principle of democracy, as well as more populist views. They furthermore express less satisfaction with the functioning of German democracy, less confidence in the country’s representative and regulatory institutions, and lower external efficacy (ALLBUS).

Political talk and democratic citizenship: effects on attitudes (unstandardized linear regression coefficients).

| I. Informal – private | II. Informal – semi-public | III. Informal – public | IV. Formal – public | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2.I | M1 | M2.II | M1 | M2.III | M1 | |||||

| Frequency | Freq|Disagree | Disagree | Frequency | Freq|Disagree | Disagree | Frequency | Freq|Disagree | Disagree | |||

| Political community (C) | P | 0.054+ | 0.061* | –0.127* | |||||||

| R | 0.048+ | –0.058+ | –0.115* | ||||||||

| Political community (A) | P | 0.082*** | 0.091*** | ||||||||

| R | –0.033+ | ||||||||||

| Diffuse support democracy (C) | P | 0.042* | 0.045* | –0.049* | –0.171*** | 0.038+ | 0.016+ | ||||

| R | 0.039* | 0.045* | –0.055* | –0.166*** | |||||||

| Diffuse support democracy (A) | P | 0.093*** | 0.085*** | 0.028* | 0.033* | –0.025* | –0.089*** | 0.026+ | 0.026*** | ||

| R | 0.028* | 0.024+ | –0.032* | –0.086*** | 0.014** | ||||||

| Liberal democracy: pluralism vs. strong leader (C) | P | 0.112*** | 0.123*** | 0.064* | 0.053*** | ||||||

| R | 0.051+ | 0.034** | |||||||||

| Liberal democracy: critical opposition and media (C) | P | 0.074** | 0.060* | 0.042* | 0.049* | 0.081** | |||||

| R | 0.043* | 0.052* | 0.058* | ||||||||

| Liberal democracy: free speech (C) | P | 0.056+ | 0.048+ | ||||||||

| R | 0.057* | ||||||||||

| Liberal democracy: Populist attitudes (reversed) (A) | P | 0.096*** | 0.081*** | 0.033+ | –0.063*** | 0.059** | –0.128*** | 0.055** | 0.015* | ||

| R | –0.026+ | –0.055** | 0.034* | –0.026+ | –0.105*** | ||||||

| Deliberative democracy: talk before voting (C) | P | 0.122** | 0.137** | 0.046* | |||||||

| R | |||||||||||

| Satisfaction with democracy (C) | P | 0.060+ | –0.175** | 0.067+ | |||||||

| R | –0.130+ | ||||||||||

| Satisfaction with democracy (A) | P | 0.066** | 0.093*** | –0.061** | –0.147*** | 0.045+ | |||||

| R | –0.039+ | –0.049* | 0.054** | 0.072*** | –0.056** | –0.098** | |||||

| Trust representative institutions (C) | P | –0.064* | 0.057* | ||||||||

| R | 0.055* | –0.039+ | –0.057* | ||||||||

| Trust representative institutions (A) | P | 0.047* | 0.040* | –0.038+ | 0.052* | –0.042* | –0.128*** | 0.015+ | |||

| R | –0.029+ | –0.041* | –0.090** | ||||||||

| Trust regulatory institutions (C) | P | 0.061* | 0.051+ | 0.063* | |||||||

| R | 0.046+ | –0.025* | |||||||||

| Trust regulatory institutions (A) | P | 0.051** | 0.047** | –0.049*** | –0.096*** | 0.037* | 0.013* | ||||

| R | –0.025+ | –0.048*** | –0.073** | ||||||||

| External efficacy (C) | P | 0.051* | 0.045+ | 0.061** | –0.099* | 0.088*** | 0.026** | ||||

| R | 0.045* | –0.090* | 0.065** | ||||||||

| External efficacy (A) | P | 0.047* | –0.059* | 0.067** | –0.038+ | –0.160*** | 0.045* | 0.015+ | |||

| R | –0.071** | –0.078** | 0.035+ | –0.046* | 0.041+ | –0.042* | –0.125*** | ||||

Note: (C) = CoDem, (A) = Allbus; P = Permissive models, R = Restrictive models. *** p < .001, ** p < .01, * p < .05, + p < .10; effects with p >= .10 not shown.

Citizenship norms: Citizens’ political talk is also associated with their normative orientations, though these effects are mostly weak and do not add up to a clear pattern (Table 2b). According to the permissive models, and partly also the restrictive models, those discussing politics more often with family members and friends (I) are more strongly committed to the norms of participation and solidarity, and in particular they are also considerably more tolerant for groups deemed politically problematic. Weak positive effects of engagement in public discussion events (IV) emerge for the norms of autonomy and participation. The semi-public and especially the public discursive spheres again seem to function differently. Conversations with acquaintances (II) appear to weaken people’s support for compliance with the legal order established by the democratic system of government. The permissive models but not the restrictive models suggest weak beneficial effects of talks with strangers (III) on people’s commitment to the norms of autonomy, solidarity, and law abidance. By contrast, when controlling for disagreement, discussions with strangers affect the norm of participation adversely.

Political talk and democratic citizenship: effects on norms (unstandardized linear regression coefficients).

| I. Informal – private | II. Informal – semi-public | III. Informal – public | IV. Formal – public | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2.I | M1 | M2.II | M1 | M2.III | M1 | |||||

| Frequency | Freq|Disagree | Disagree | Frequency | Freq|Disagree | Disagree | Frequency | Freq|Disagree | Disagree | |||

| Autonomy (C) | P | 0.052* | 0.049+ | 0.050+ | 0.030** | ||||||

| R | 0.054* | 0.022+ | |||||||||

| Participation (C) | P | 0.116** | 0.121** | –0.123+ | 0.046** | ||||||

| R | –0.125+ | 0.037* | |||||||||

| Solidarity (C) | P | 0.074* | 0.075* | 0.071* | 0.074* | ||||||

| R | 0.065+ | 0.062+ | 0.060+ | 0.078* | |||||||

| Law abidance (C) | P | –0.057* | –0.063* | 0.059+ | |||||||

| R | –0.057* | –0.061* | |||||||||

| Tolerance (C) | P | 0.163** | 0.158* | 0.178* | |||||||

| R | 0.151* | ||||||||||

Note: (C) = CoDem, (A) = Allbus; P = Permissive models, R = Restrictive models. *** p < .001, ** p < .01, * p < .05, + p < .10; effects with p >= .10 not shown.

Political participation: As shown in Table 2c, citizens’ political activities are strongly affected by casual conversations in the discursive sphere of private political talk (I). The more frequently they discuss politics within the realms of kinship and friendship, the more likely they perform all modes of political participation. Unlike political support and norms, these mobilizing effects emerge consistently in both permissive and restrictive models (except for turnout in the two CoDem versions). Similar results emerge for engagement in formalized public discussions (IV). Frequent conversations with co-workers or neighbors (II) are only associated with a higher likelihood to vote, and to participate in non-institutionalized (ALLBUS) as well as protest activities (CoDem). In stark contrast, political conversations with strangers (III) appear to decrease the likelihood to vote. The only robust positive effect of engagement in the public discursive sphere of everyday political talk concerns participation in protest activities (ALLBUS). However, when controlling for disagreement, we see stable negative effects for non-institutionalized participation in the ALLBUS data and for protest participation in the CoDem data, suggesting that our equivalent but dissimilar measures might hide relevant differences between specific forms of political activity within the same types.

Political talk and democratic citizenship: effects on behavior (logit coefficients).

| I. Informal – private | II. Informal – semi-public | III. Informal – public | IV. Formal - public | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2.I | M1 | M2.II | M1 | M2.III | M1 | |||||

| Frequency | Freq|Disagree | Disagree | Frequency | Freq|Disagree | Disagree | Frequency | Freq|Disagree | Disagree | |||

| Turnout intention (C) | P | 3.473*** | 3.162*** | –1.687** | –3.257*** | 0.678+ | |||||

| R | –1.375* | –2.257* | |||||||||

| Turnout recall (C) | P | 2.195* | 2.388* | 1.828+ | –1.714+ | –5.090** | |||||

| R | –4.116* | ||||||||||

| Turnout recall (A) | P | 2.369*** | 1.851*** | 0.592* | –1.102* | 0.680+ | 0.238+ | ||||

| R | 1.438*** | 0.938* | 0.594* | 0.679+ | |||||||

| Institutionalized participation (A) | P | 1.379*** | 1.250*** | 0.353+ | 0.316+ | 0.839*** | 0.854*** | ||||

| R | 0.721** | 0.633** | 0.709** | 0.750*** | |||||||

| Non-institutionalized participation (C) | P | 1.102** | 1.164** | 0.722* | 0.722+ | 1.431*** | |||||

| R | 0.725+ | 0.767+ | 1.317*** | ||||||||

| Non-institutionalized participation (A) | P | 1.426*** | 1.228*** | 0.409+ | 0.431* | –1.348*** | 1.602*** | 1.200*** | |||

| R | 0.807** | 0.600* | 0.474* | –1.325** | 1.480*** | 1.102*** | |||||

| Protest participation (C) | P | 1.411*** | 1.436*** | 0.656* | 0.548+ | –1.145* | 0.859** | 1.418*** | |||

| R | 0.778* | 0.813* | 0.688* | 0.595+ | –1.284* | 1.232*** | |||||

| Protest participation (A) | P | 1.955*** | 1.906*** | 0.427+ | –0.535* | 0.544* | 0.964*** | 0.885*** | 0.928*** | ||

| R | 1.611*** | 1.571*** | –0.515* | 0.403+ | 0.895*** | 0.683** | 0.889*** | ||||

Note: (C) = CoDem, (A) = Allbus; P = Permissive models, R = Restrictive models. *** p < .001, ** p < .01, * p < .05, + p < .10; effects with p >= .10 not shown.

6.2 Disagreement Experiences in Everyday Political Talk

Political support: Encounters with disagreement affect political support most consistently when they occur in conversations within weak ties (II; Table 2a). According to both permissive and restrictive models, opinion diversity is associated with stronger political support in many of its facets. For the ALLBUS data, satisfaction with democracy and external efficacy are also responsive to disagreement in strong ties (I). In a similar vein, such experiences appear to strengthen support for the liberal-democratic principle of free speech. We also see several positive effects of disagreement during conversations with strangers (III)—for diffuse and specific support for democracy only in the permissive models but concerning external efficacy (CoDem) and support of the liberal democratic principle of critical opposition and media in permissive and restrictive models alike.

Citizenship norms: Disagreement experiences in strong ties (I) strengthen the norm of autonomy (Table 2b). Heterogeneous conversations with strangers (III) appear beneficial for supporting the norm of solidarity and especially tolerance for which particularly strong effects emerge in both permissive and restrictive models.

Political participation: Table 2c shows a number of positive associations between exposure to disagreement and citizens’ political behavior. Experiences of political heterogeneity appear overall most consequential for participation when they occur in conversations with people one does not know (III). Here positive effects on all types of participation are evident (except CoDem for turnout), and they are mostly robust to restrictive model specifications. With great consistency, though overall most strongly for non-institutionalized participation, encounters with disagreement in the public discursive sphere of casual talk with strangers thus go hand in hand with an increased inclination to be politically active. For disagreeable conversations within strong and weak ties findings are much less pronounced. A robust effect of exposure to disagreement emerges only within weak ties (II) for participation in protest activities.

6.3 Discussion

Obviously, our data do not support H1. The assumed, unequivocally positive association between all kinds of political talk and the three dimensions of democratic citizenship does not materialize. The data are also at best partly in line with the more specific H2.1. If the assumed beneficial role of political talk were conditional upon its effectiveness with regard to policy-making (Mansbridge 1999), substantial positive effects would emerge for purposive discussions at organized public events but not, or at least to a lesser extent, for engagement in any of the three discursive spheres of non-purposive, politically inconsequential everyday communication. Consistent with the hypothesis, we do find a number of positive, though mostly weak effects of engagement in the public arena of formal discussion events. Regarding political participation, its relevance appears especially clear-cut. By contrast, concerning the three types of informal conversation the evidence is mixed. Since the partly quite strong associations of conversations with family members and friends with political support and norms of citizenship almost completely evaporate in the restrictive models, we subscribe to the conservative interpretation that engagement in the private discursive sphere of everyday political talk is not relevant for these two pillars of democratic citizenship. This is in line with H2.1. However, regarding political participation, even the restrictive models signal a favorable role of political talk within strong ties. In addition, for everyday political talk within weak ties, our analyses also detect positive effects on certain manifestations of political support and participation that are robust to varying model specifications. These findings speak for a limited though non-negligible positive role of political conversations within social networks for democratic citizenship. Accordingly, the assumption of informal everyday political talk being irrelevant, as implied by H2.1, cannot be upheld. The ‘self-transformative’ effects of political talk with regard to ‘better’ democratic citizenship do not seem to depend on its effectiveness in the process of democratic decision-making.

Concerning the role of casual political talk with strangers, our findings are more clear-cut and largely in line with H2.2. Frequent engagement in the discursive sphere of public everyday political talk appears to diminish political support in a wide range of its manifestations, to weaken the norm that citizens should participate in politics, and to render it less likely that people vote. At the same time, it seems to encourage protest behavior.

H3 expected a largely positive role of disagreement experiences in the discursive spheres of informal everyday political talk. To some extent this expectation is borne out by our data. Our findings suggest that disagreement does matter—not for all facets of democratic citizenship, to be sure, and not always strong enough to persist in the restrictive models. But where it matters its consequences are always beneficial. None of our dependent variables is affected negatively by opinion differences that people encounter during casual conversations, not even political participation that according to Mutz (2006) should be undermined by experiences of heterogeneity. Our analyses instead point to a mobilizing role of disagreement, especially in the public discursive sphere of informal conversations with strangers. At the same time our evidence confirms findings from earlier research that suggest positive consequences of political disagreement for tolerance. It also adds an interesting nuance to this line of research because it suggests that it is not disagreement with network partners—previous studies’ sole object—but with strangers that counts for citizens’ tolerance.

7. Conclusion

Our study provides the first comprehensive analysis of the consequences of citizens’ political talk in all four discursive spheres for the triad of democratic citizenship that encompasses (1) the attitudinal dimension of support for the democratic political system, (2) the normative dimension of views about good citizenship, and (3) the behavioral dimension of active participation in the political process.

Despite its scope and complexity, our study established a remarkably clear picture. The simple baseline hypothesis that all kinds of engagement in political talk exert unequivocally positive effects on all facets of democratic citizenship finds no support in our data. Systematic effect patterns emerged between but rarely within the three pillars of democratic citizenship. There is no empirical support for the claim that beneficial effects of political talk are conditional on its ‘uptake’ (Goodin & Dryzek 2006) in the formal political process. What does make a large difference, however, is which discursive spheres citizens engage in.

Engagement in two of these arenas is quite unequivocally positively associated with democratic citizenship—the discursive sphere of informal conversations within strong ties in private settings, and the discursive sphere of formalized public discussion events. However, our conservative modeling criteria lead to the conclusion that for political support and citizenship norms these relationships may be largely due to other determinants than political talk. Concerning political participation, by contrast, our data suggest a more robust mobilizing role of political talk within the informal contexts of kinship and friendship as well as the formal context of organized events.

This contrasts strongly with our results for casual political talk with unknown persons. They point to a partly problematic role of this discursive sphere for democratic citizenship. Even when applying strict criteria to the empirical evidence, conversations with strangers appear to diminish political support in a wide range of its manifestations, to weaken the norm that citizens should take part in politics, and to render it less likely that they participate in elections but more likely to take part in protest activities. The implications of citizens’ engagement in the semi-public discursive sphere of everyday political talk within weak ties are ambivalent, corresponding to its intermediate location between the at least partially beneficial private discursive sphere and the in many respects detrimental public discursive sphere of everyday political talk.

These observations are worrisome from a deliberative democratic point of view. According to theorists of the public sphere it is primarily in talks with unknown others, rather than within the confines of social networks, that society at large engages in the great conversation with itself that is advocated as core element of deliberative democratic opinion formation. Other theorists place great hopes in weak ties’ ability to establish bridges between different social networks (Tanasoca 2020). Our findings cast doubt on these expectations. Engagement in the public and to a lesser extent the semi-public discursive spheres appears to impair democratic citizenship, especially when the opinions voiced during such conversations are homogeneous. What renders these modes of political talk so harmful for democratic citizenship? Presumably, the destructive role of these modes of political talk results from ‘fast’ superficial processing of their political content (Stoker et al. 2016) and the disturbing phenomenon that ranting about politics seems to be a particularly suitable tool for defining selves and managing social interactions whenever people need to find common ground with unknown or not well-known others (Bøggild et al. 2021; Saunders & Klandermans 2020).

On a more positive note, our findings suggest that experiencing society’s political diversity during informal political discussions (Nir 2017) is a moderately effective productive force for democratic citizenship. Wherever such associations emerged, they were unfailingly positive. Experiences of heterogeneity seem to matter more at the fringes or outside of social networks than in the core networks of family and friends. Disagreement thus to some extent counteracts the negative consequences of intense engagement in the semi-public and public discursive spheres.

Notes

- The CoDem survey was conducted as part of the project ‘Conversations of Democracy: Citizens’ Everyday Communication in the Deliberative System (CoDem)’ under a grant of the German National Science Foundation (DFG). Following the model of major studies of personal influence the survey was conducted locally. Its site was Mannheim, a medium-sized German city with a highly variegated social structure and a good mix of economic, cultural and political milieus. It utilized a register-based one-stage random sample of residents entitled to vote at the 2017 German Federal Election. 1,600 computer-assisted personal interviews were completed between May and September 2017. The second panel wave was conducted by telephone from January to March 2018 (N = 877). For methodological details, see Grill et al. (2018). ⮭

- The 2018 ALLBUS was conducted by GESIS Leibniz Institute of the Social Sciences. It was based on a two-stage random sample of Germany’s resident population aged 18 or older (first stage: municipalities; second stage: residents selected from municipal registers), and 3,477 interviews were collected by means of computer-assisted personal interviewing between April and September 2018 (for methodological details see https://www.gesis.org/en/allbus/contents-search/study-profiles-1980-to-2018/2018). The dataset is available at the GESIS data archive (dataset no. ZA5272). ⮭

- Of course, our study faces the common problem that observational approaches cannot unambiguously substantiate causal claims. Our analyses cannot rule out the possibilities of reverse or reciprocal two-way causation. We address this problem by opting for a conservative strategy of analysis (see section 5.4). The CoDem survey allows us to address concerns about potential simultaneity bias at least to some extent since it ran the independent variables in the first panel wave and most of the dependent variables in the second wave, conducted several months ⮭

- While the ALLBUS asked for the frequency of political talks in general (registered on 5-point scales from ‘never’ to ‘very often’), the CoDem survey more specifically referred to ‘face-to-face but also telephone and online conversations’ held during the last six months (registered on 5-point scales from ‘never’ to ‘daily or almost every day’). Closer analysis reveals that CoDem respondents’ everyday political talk predominantly took the form of face-to-face communication (less than six percent discussed politics at least in similar proportions offline and online, almost no one relied exclusively on digital communication). ⮭

- Scales from ‘never’ to ‘very often’. ⮭

- See Supplementary Materials for full documentation of all models. ⮭

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

1 Almond, G. A., & Verba, S. (1963). The civic culture. Political attitudes and democracy in five nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9781400874569

2 Atkin, C. K. (1972). Anticipated communication and mass-media information-seeking. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36, 188–199. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1086/267991

3 Bächtiger, A. (2016). Empirische Deliberationsforschung. In W. O. Lembcke, C. Ritzi & S. G. Schaal (Eds.), Zeitgenössische Demokratietheorie, Band 2: Empirische Demokratietheorien (pp. 251–278). Wiesbaden: Springer. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-06363-4_11

4 Bøggild, T., Aarøe, L., & Petersen, M. B. (2021). Citizens as complicits: Distrust in politicians and biased social dissemination of political information. American Political Science Review, 115(1), 269–285. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000805

5 Carlson, T. N., Abrajano, M., & Bedolla, L. G. (2020). Talking politics. Political discussion networks and the new American electorate. New York: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190082116.001.0001

6 Cinelli, C., Forney, A., & Pearl, J. (2022). A crash course in good and bad controls. Sociological Methods & Research (Online first). DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/00491241221099552

7 Cohen, J. (1989). Deliberation and democratic legitimacy. In A. P. Hamlin & P. N. Pettit (Eds.), The good polity. Normative analysis of the state (pp. 18–34). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

8 Conover, P. J., & Miller, P. R. (2018). Taking everyday political talk seriously. In A. Bächtiger, J. S. Dryzek, J. Mansbridge, & M. Warren (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of deliberative democracy (pp. 378–391). Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198747369.013.12

9 Dalton, R. J. (2004). Democratic challenges, democratic choices: The erosion of political support in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199268436.001.0001

10 Dalton, R. J. (2008). Citizenship norms and the expansion of political participation. Political Studies, 56(1), 76–98. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00718.x

11 Denters, B., Gabriel, O. W., & Torcal, M. (2007). Norms of good citizenship. In J. W. van Deth, J. R. Montero, & A. Westholm (Eds.), Citizenship and involvement in European democracies: A comparative analysis (pp. 88–108). New York: Routledge.

12 Easton, D. (1975). A re-assessment of the concept of political support. British Journal of Political Science, 5(4), 435–457. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400008309

13 Elstub, S. (2014). Deliberative minipublics: Issues and cases. In S. Elstub & P. McLaverty (Eds.), Deliberative democracy: Issues and cases (pp. 166–188). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9780748643509

14 Fleuß, D., Helbig, K., & Schaal, G. S. (2018). Four parameters for measuring democratic deliberation: Theoretical and methodological challenges and how to respond. Politics and Governance, 6(1), 11–21. DOI: http://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v6i1.1199

15 Goffman, E. (1963). Behavior in public places. Notes on the social organization of gatherings. Glencoe: Free Press.

16 Goodin, R. E., & Dryzek, J. S. (2006). Deliberative impacts: The macro-political uptake of mini-publics. Politics & Society, 34(2), 219–244. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0032329206288152

17 Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(3), 1360–1380. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1086/225469

18 Grill, C., Schmitt-Beck, R., & Metz, M. (2018). Studying the ‘conversations of democracy’: Research design and data collection. MZES Working Paper 173. Mannheim: MZES. https://www.mzes.unimannheim.de/publications/wp/wp-173.pdf

19 Gutmann, A., & Thompson, D. (1996). Democracy and disagreement. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

20 Habermas, J. (1989). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society. Cambridge: Polity.

21 Habermas, J. (1996). Between facts and norms. Contributions to a discourse theory of law and democracy. Cambridge: MIT Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/1564.001.0001

22 Hauser, G. A. (1999). Vernacular voices: The rhetoric of publics and public spheres. Columbia/SC: University of South Carolina Press.

23 Hendriks, C. M. (2006). Integrated deliberation: Reconciling civil society’s dual role in deliberative democracy. Political Studies, 54(3), 486–508. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2006.00612.x

24 Huckfeldt, R., Johnson, P., & Sprague, J. (2004). Political disagreement. The survival of diverse opinions within communication networks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511617102

25 Huckfeldt, R., & Sprague, J. (1995). Citizens, politics, and social communication. Information and influence in an election campaign. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511664113

26 Jacquet, V., & van der Does, R. (2020). The consequences of deliberative minipublics: Systematic overview, conceptual gaps, and new directions. Representation (pp. 1–11). DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2020.1778513

27 Klofstad, C. A., Sokhey, A., & McClurg, S. D. (2013). Disagreeing about disagreement: How conflict in social networks affects political behavior. American Journal of Political Science, 57(1), 120–134. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2012.00620.x

28 Kuyper, J. W. (2018). The instrumental value of deliberative democracy – Or, do we have good reasons to be deliberative democrats? Journal of Public Deliberation, 14(1). https://delibdemjournal.org/article/id/563/. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.291

29 Leite Viegas, J. M. (2007). Political and social tolerance. In J. W. van Deth, J. R. Montero & A. Westholm (Eds.), Citizenship and involvement in European democracies: A comparative analysis (pp. 109–132). New York: Routledge.

30 Mansbridge, J. (1999). On the idea that participation makes better citizens. In S. L. Elkin (Ed.), Citizen competence and democratic institutions (pp. 291–325). University Park/PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

31 Marsden, P. V. (1987). Core discussion networks of Americans. American Sociological Review, 52, 122–131. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/2095397

32 Marshall, T. H. (1950). Citizenship and social class. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

33 Morrell, M. E. (2005). Deliberation, democratic decision-making and internal political efficacy. Political Behavior, 27, 49–69. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-005-3076-7

34 Mutz, D. C. (2006). Hearing the other side. Deliberative versus participatory democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511617201

35 Mutz, D. C. (2008). Is deliberative democracy a falsifiable theory? Annual Review of Political Science, 11, 521–538. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.081306.070308

36 Myers, C. D., & Mendelberg, T. (2013). Political deliberation. In L. Huddy, D. O. Sears & J. S. Levy (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political pychology (2nd ed., pp. 699–734). Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199760107.013.0022

37 Neblo, M. A. (2015). Deliberative democracy between theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139226592

38 Nir, L. (2017). Disagreement in political discussion. In K. Kenski & K. H. Jamieson (Eds.), Oxford handbook of political communication (pp. 713–729). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

39 Noelle-Neumann, E. (1974). The spiral of silence: A theory of public opinion. Journal of Communication, 24(2), 43–51. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1974.tb00367.x

40 Norris, P. (1999). Introduction: The growth of critical citizens? In P. Norris (Ed.), Critical citizens: Global support for democratic governance (pp. 1–27). Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/0198295685.003.0001

41 Oser, J. (2022). Protest as one political act in individuals’ participation repertoires: Latent class analysis and political participant types. American Behavioral Scientist, 66(4), 510–532. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/00027642211021633

42 Pattie, C., Seyd, P., & Whiteley, P. (2004). Citizenship in Britain. Values, participation and democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511490811

43 Pincock, H. (2012). Does deliberation make better citizens. In T. Nabatchi, J. Gastil, G. M. Weiksner & M. Leighninger (Eds.), Democracy in motion: Evaluating the practice and impact of deliberative civic engagement (pp. 135–162). Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199899265.003.0007

44 Richards, R. C., & Neblo, M. (2022). Active is as active does: Deliberative and non-deliberative communication in context. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 18(2), 1–17. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/10.16997/jdd.941

45 Rolfe, M., & Chan, S. (2018). Voting and political participation. In J. N. Victor, A. H. Montgomery & M. Lubell (Eds.), Oxford handbook of political networks (pp. 357–382). Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190228217.013.15

46 Sandoval-Hernández, A., Claes, E., Savvides, N., & Isac, M. M. (2021). Citizenship norms and tolerance in European adolescents. In E. Treviño, D. Carrasco, E. Claes, & K. J. Kennedy (Eds.), Good citizenship for the next generation (pp. 147–170). Cham: Springer International. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75746-5_9

47 Saunders, C., & Klandermans, B. (Eds.) (2020). When citizens talk about politics. New York: Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9780429458385

48 Schmitt-Beck, R., & Grill, C. (2020). From the living room to the meeting hall? Citizens’ political talk in the deliberative system. Political Communication, 37(6), 832–851. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1760974

49 Schmitt-Beck, R., & Lup, O. (2013). Seeking the soul of democracy: A review of recent research into citizens’ political talk culture. Swiss Political Science Review, 19(4), 513–538. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12051

50 Schnaudt, C., van Deth, J. W., Zorell, C., & Theocharis, Y. (2021). Revisiting norms of citizenship in times of democratic change. Politics, (online first) (pp. 1–18). DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/02633957211031799

51 Schudson, M. (1997). Why conversation is not the soul of democracy. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 14(4), 297–309. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/15295039709367020

52 Searing, D. D., Solt, F., Conover, P. J., & Crewe, I. (2007). Public discussion in the deliberative system: Does it make better citizens? British Journal of Political Science, 39(4), 587–618. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123407000336

53 Steiner, J. (2012). The foundations of deliberative democracy. Empirical research and normative implications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139057486

54 Stevenson, H., & Dryzek, J. S. (2014). Democratizing global climate governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139208628

55 Stoker, G., Hay, C., & Barr, M. (2016). Fast thinking: Implications for democratic politics. European Journal of Political Research, 55(1), 3–21. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12113

56 Straits, B. C. (1991). Bringing strong ties back in. Interpersonal gateways to political information and influence. Public Opinion Quarterly, 55, 432–448. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1086/269272

57 Tanasoca, A. (2020). Deliberation naturalized. Improving real existing deliberative democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198851479.001.0001

58 Thomassen, J., & van Ham, C. (2017). A legitimacy crisis of representative democracy? In C. van Ham, J. Thomassen, K. Aarts, & R. Andeweg (Eds.), Myth and reality of the legitimacy crisis (pp. 3–16). Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198793717.003.0001

59 Torcal, M., & Maldonado, G. (2014). Revisiting the dark side of political deliberation: The effects of media and political discussion on political interest. Public Opinion Quarterly, 78(3), 679–706. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfu035

60 van Deth, J. W. (2003). Vergleichende politische Partizipationsforschung. In D. Berg-Schlosser & F. Müller-Rommel (Eds.), Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft, 4th ed. (pp. 167–187). Opladen: Leske + Budrich. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-322-86382-9_8

61 van Deth, J. W. (2007). Norms of citizenship. In R. J. Dalton & H.-D. Klingemann (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political behavior (pp. 402–417). Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199270125.003.0021

62 van Deth, J. W., Montero, J. R., & Westholm, A. (Eds.) (2007). Citizenship and involvement in European democracies: A comparative analysis. New York: Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9780203965757

63 van Ham, C., & Thomassen, J. (2017). The myth of legitimacy decline. An empirical evaluation of trends in political support in established democracies. In C. van Ham, J. Thomassen, K. Aarts, & R. Andeweg (Eds.), Myth and reality of the legitimacy crisis (pp. 17–34). Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198793717.001.0001

64 Verba, S., Schlozman, K. L., & Brady, H. E. (1995). Voice and equality. Civic voluntarism in American politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1pnc1k7

65 Warren, M. E. (1992). Democratic theory and self-transformation. American Political Science Review, 86(1), 8–23. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/1964012

66 Weintraub, J. (1997). The theory and politics of the public/private distinction. In J. Weintraub & K. Kumar (Eds.), Public and private in thought and practice. Perspectives on a grand dichotomy (pp. 1–42). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.