Introduction

Can online deliberation over a highly controversial issue engender democratic benefits that are predicted by the framework of deliberative theory, particularly vis-á-vis South Korea’s feminist movement? One of the primary agendas in the growing feminist movement in South Korea is a public reassessment of the legal status of abortion. In 2012, South Korean courts upheld the constitutionality of the legislation banning abortion, yet a recent public opinion survey showed that more than half of the population (51.9%) supported lifting the ban (Realmeter, 2017). Alongside a large scale rally against the criminalization of abortion and the rise of women’s movement, the Constitutional Court finally eased the ban on abortions in April 2019.

However, antipathy against feminism has been on the rise in male-dominated online communities, thus deepening fault lines between two gender groups in younger generations (Jeong & Lee, 2018). Before and after the decision from the Constitutional Court was made public regarding the abortion ban, online communities and news forums were overwhelmed with comments about the decision, reflecting a stark dichotomy between pro-life and pro-choice (Ock, 2019). Such public hostility eventually led citizens to speak less of their own opinions and be hesitant to expose themselves to disagreeing viewpoints on gender issues (Steger, 2016).

In what follows, we examined whether a well-structured online deliberation can bring about democratic benefits in a highly polarized context of gender-related issues. As South Korean gender-related dialogue is becoming even more hostile, especially through online platforms, it may be important for people to have some opportunities to deliberatively reflect on relevant issues. We explored whether applying some essential deliberative rules (such as cross-cutting exposure and equality) into political conversations on a messaging application can 1) improve the rationality and civility of discussions on abortion, 2) promote healthy political participation regarding gender-related issues, and 3) foster empathetic and tolerant attitudes toward people holding different opinions.

Our study contributes to the deliberation literature by focusing on one of the relatively understudied principles of deliberation: equality. Contrary to the normative emphasis on the rule of equality, neither the meaning of the rule has been coherently conceptualized nor have the effects of equality been systematically investigated. Here, we borrow the framework of Friess and Eilders (2015) and define the rule of equality as one of the key features in the input dimension of deliberative procedures— providing an equal opportunity to everyone participating in a discussion to address one’s opinion at a minimum. We specifically focus on how the rule of equality moderates the effects of cross-cutting exposure on desirable outcomes, such as the deliberative quality of discussions, political participation, and civic virtues. Beyond solely examining the consequences of encountering dissonant viewpoints (e.g., Mutz, 2006), we argue that greater attention to the equality rule and its interaction with the condition of opinion diversity can shed light on how to construct a successful deliberative intervention in online discussions. Empirical findings on deliberative effects have been at times at odds with theoretical assumptions (Mutz, 2008), but this gap may have emerged from the lack of empirical testing on the interactions between different deliberative conditions.

We also contribute to the study of cross-cutting exposure or disagreement in general. By varying the level of disagreement to which an individual gets exposed, we improve previous approaches that rely on individuals’ perceived sense of disagreement (e.g., Mutz, 2002). Our focus on egocentric diversity is useful since it can bring up new scholarly discussions about how much disagreement is beneficial for a healthy democracy (Esterling, Fung, & Lee, 2015). Further, previous studies focusing on the political effects of cross-cutting deliberations (e.g., Grönlund et al., 2015; Wojcieszak, 2011) have mostly examined changes in issue attitudes after face-to-face deliberation events. Here, we specifically inquire whether cross-cutting exposure and the rule of equality in online deliberation can interactively bring about democratic outcomes.

To explore the aforementioned relationships, this study designed an experiment on online deliberation via KaKaoTalk, South Korea’s most widely used messenger platform. In particular, its Open Chatting functions provide opportunities for anonymous users to freely participate in informal discussions over a diverse range of issues. It also enabled us to assess the deliberative qualities in a more objective and unobtrusive manner: a content analysis of discussion scripts.

In short, we examine whether cross-cutting exposure and the rule of equality—components required for deliberative discussions—can help us successfully achieve some desirable outcomes expected from the deliberative process. We empirically test some of the normative assumptions about the benefits of civic deliberation, rather than accepting such consequences as a given, with regard to one of the most critical gender issues in South Korea: legalization of abortion.

Literature Review

When we talk to people who disagree with us

Although the answer to the question of “what is the most necessary condition for deliberation?” has been controversial (Mutz, 2008), there are generally accepted core elements of deliberation, including exposure to dissimilar opinions, diversity of representation, provision of equal participation, showing respect to dissimilar others, and reasonable justification of arguments (e.g., Fishkin, 2011; Gutmann & Thompson, 1996; Thompson, 2008). When such conditions for deliberation are met, participants are to become more efficacious (Barabas, 2004), sophisticated (Gastil, 2006), reflective (McLeod et al., 1999), and participatory in politics or other social activities (Gastil et al., 2002; Roh & Min, 2009).

Experiencing disagreement, inter alia, has been accentuated as one of the foremost conditions to be met for deliberation (e.g., Gutmann & Thompson, 1996). By coming in contact with dissimilar views, our conceptions of the discussed matter can approximate to a better truth (Mill, 1859/2015). By so doing, we attain great opportunities to reflect on the oppositional views as well as ourselves: a cognitive process that transforms us into a public entity (Habermas, 1989). While demonstrating political effects of exposure to disagreement has been confounded with inconsistent conceptualizations and measurements of disagreement itself (Klofstad et al., 2013), we concentrate on how much disagreement is occurring at the individual level in a conversational setting, i.e., egocentric diversity or cross-cutting exposure. Utilizing previous conceptualizations of egocentric network diversity (e.g. Mutz, 2006; Scheufele et al., 2006; Song & Eveland Jr, 2015), we defined egocentric diversity as the amount of dissimilar opinions that one encounters during a group discussion, i.e., cross-cutting exposure.

Cross-cutting exposure and deliberativeness. If exposure to different views is a sine qua non of deliberation, can it actually increase the deliberativeness of political discussions? A sufficient amount of evidence to this question has not been accumulated (Mutz, 2008). Two different tasks need to be accomplished to succinctly address this literature gap: clarifying the meaning of deliberativeness and examining a causal relationship between deliberative conditions and deliberativeness.

Given that elements that constitute the deliberative quality of political conversations are manifold, we identified two main dimensions of deliberativeness based on some previous research: reason-giving (rationality of the discursive acts) and respecting the other side (civility of the discursive acts). In previous studies, the deliberative qualities of political discussions have been operationalized as the level of justification and reciprocity or constructiveness during conversations (e.g., Bächtiger & Parkinson, 2019; Jaidka et al., 2019; Steenbergen et al., 2003; Stroud et al., 2015). Here, rationality resonates with the former, whereas civility resonates with the latter. Unlike just any sort of conversation, deliberation should be rooted in public justification through reasonable argumentation, i.e., rationality (Elster, 1998). In addition to an individual’s ability to express their own idea coherently and logically, deliberation also requires a certain level of civility to genuinely listen to dissimilar opinions (Papacharissi, 2004; Park, 2000). Considering that explicitly uncivil behaviors are seldom found in structured discussions, we concentrate on rationality and civility as the essential attributes constituting the deliberative quality of political discussions.

Then, how can exposure to dissimilar opinions influence these two dimensions of deliberativeness, rationality and civility? Imagine a situation when you need to persuade others who manifest a different perspective from yours: we automatically look for legitimate reasons to justify our positions. As Larmore (1990) explains, such a confrontation itself encourages us to develop our arguments in a more sophisticated way. It also allows the discussion to be less arbitrary and more justifiable by making us aware of opposing views that coexist (Manin, 1987).

However, perceived differences among discussants may create a sense of conflicts and anxiety during a conversation, possibly making them less willing to discuss a given topic in a reason-giving manner (Eliasoph, 1998). It may even direct the conversation to a more emotional and less reflective way. Furthermore, those who perceive themselves as having minority opinions under high cross-cutting exposure may not express themselves openly for fear of being isolated (Moy et al., 2001; Noelle-Neuman, 1993), thereby exacerbating biased interactions among group members (Bettencourt & Dorr, 1998).

A similar question can be raised with regard to civility. Above all, interacting with people of differing views is essential to a more sophisticated understanding of others (Park, 2000). At the same time, however, displaying disagreement explicitly can be counterproductive for civil interactions, since discussing a contentious political issue with people with different opinions often triggers face-threatening pressures (Eliasoph, 1998; Mutz, 2006).

As discussed so far, empirical evidence for the thesis that cross-cutting exposure actually increases deliberativeness remains relatively equivocal. Reflecting on these inconsistent predictions in prior research, our first research question has been formulated as follows:

RQ1: How does cross-cutting exposure during the discussion on a gender issue influence the deliberativeness of the discussion, i.e., rationality and civility?

Cross-cutting exposure, political participation and civic virtues. Findings on the relationship between political disagreement and participatory behaviors have also been varied. On one hand, cross-cutting exposure holds the potential to increase participatory motivations; participants can enjoy political disagreement itself by deeming it constructive (Esterling, Fung, & Lee, 2015), and become more engaged in political issues (MacKuen et al., 2010). In addition to enhancing political efficacy and interest, exposure to dissimilar opinions can increase attitudinal certainty, thus heightening political participation (Sunstein, 2002; Wojcieszak, 2011).

On the other hand, a raft of empirical evidence has suggested the contrary; individually-encountered disagreements are positively associated with ambivalence and cross-pressure, and thus causing withdrawal from political participation (Huckfeldt, Morehouse, & Osborn, 2004; Mutz, 2002). Exposure to heterogeneous ideas may create neutralized attitudes by helping people realize that political issues are not necessarily dichotomous (Meffert et al., 2004) or by increasing motivation to think about alternatives (Vinokur & Burnstein, 1978). It may, thereby, lead to less participation. Hovland, Janis, and Kelley (1953) also state that “vacillation, apathy and loss of interest in conflict-laden issues” (p. 283) can be caused by conflicting cross-pressures. This controversy has been persistently brought up by academics as a “conflict between two major values in deliberative theory—participation and deliberation itself” (Thompson, 2008, p. 511), although the latest meta-analysis by Matthes and his colleagues (2019) concludes that there is no direct relationship between cross-cutting exposure and political participation.

Similarly, findings have been inconsistent with regard to whether exposure to disagreeing opinions can succeed or fail to engender civic virtues such as empathy and tolerance. As proposed by the contact hypothesis (Allport, 1954), appreciating disparate perspectives is linked with perspective-taking—that is, a cognitive form of empathy (Mutz, 2002)—, which is possibly connected to enhanced political tolerance (Robinson, 2010). However, exposure to conflictual opinions often fails to shift the level of empathy and tolerance toward differences due to inter-group bias; people tend to privilege in-group arguments and devalue out-group members’ opinions (Mendelberg, 2002).

Against this backdrop, our inquiries on the effects of cross-cutting exposure on important democratic outcomes have been put forward as follows:

RQ2: How does cross-cutting exposure during the discussion on a gender issue influence political participation in gender-related activities?

RQ3: How does cross-cutting exposure during the discussion on a gender issue influence civic virtues such as empathy and tolerance?

When we talk to people who disagree with us in an equal manner

Is there another possible intervention that may help discussants to realize the assumed, but often obscure, benefits of deliberation in the real-world contexts? We argue that talking with an equality rule is essential when multifarious opinions are exchanged. In this regard, we attend to how the rule of equality moderates the effects addressed in RQ1, RQ2, and RQ3, assuming that some positive outcomes of cross-cutting exposure can be enhanced when combined with the equality rule.

Compared to the theoretical emphasis on the rule of equality as a normative precondition for proper deliberation (e.g., Thompson, 2008), attention to the conceptualization of the rule of equality has remained rather scant. Here, the online deliberation framework, suggested by Friess and Eilders (2015), can be useful: equality in deliberation is to be defined in terms of input (prior to deliberation), throughput (during deliberation), and output (after deliberation). When the principle of equality is conceptualized in the input dimension, it mainly addresses whether all citizens, who are influenced by collective decision-making, are able to voice their reasons in the process without any obstacles, thereby making all viewpoints expressed and heard (Fishkin, 1995). Here, the principle of equality concerns avoiding both domination and exclusion during deliberation by incorporating fair procedures (Thompson, 2008). This approach to deliberative equality tackles with a procedural issue providing equal opportunities to engage in a discussion.

Equality norms have also been defined in the throughput or output of deliberation (Albrecht, 2006; Besley & McComas, 2005; Zhang, 2015). To quantify the degree of equality on the communicative throughput level, Albrecht (2006) assessed the relative (in)equality of speech distribution in a debate (“participant equality” in his terms) using the Gini coefficient. When equality is conceptualized as the expected output of deliberation, it has been measured with participants’ feeling that the interaction went reciprocal, fair, and legitimate (Besley & McComas, 2005; Zhang, 2015). For instance, Besley and McComas (2005) point out the importance of perceived fairness and legitimacy in heightening citizens’ level of satisfaction with public engagement. Similarly, Zhang (2015) finds that perceived procedural fairness is a significant predictor of enjoyment and intentions for future participation in deliberation events.

Equality can refer to a number of properties within deliberative settings, yet it has rarely been experimentally examined at the individual level. In this study, we focus on a particular input-related form of discursive equality: the provision of equal opportunities to speak during group discussions. By providing at least three opportunities to talk about their arguments and reasons, we sought to equalize the quantity of given speech from the participants, to the extent that the equality rule does not demotivate them from freely exchanging their thoughts. Ideally, such forms of discursive equality can be realized via active moderation and rule-enforcing by facilitators (Coleman & Gøtze, 2001; Fishkin, 2011).

By pairing the experiment with a content analysis of conversation transcripts, we examine the effects of cross-cutting exposure moderated with the rule of equality (the input dimension) on deliberative equalities of shared discussions (the throughput dimension) and behavioral intentions and attitudes (the output dimension). We first inquire whether fulfilling both conditions, cross-cutting exposure and the rule of equality, can enhance deliberative qualities of political discourse, i.e., rationality and civility. Under conversational domination, one may find it difficult to reflect on a given issue in a balanced way (Gastil, 2006; Morrell, 1999), thereby hurting the overall rationality of a political discussion. Structured intervention with the rule of equality can also assure participants that the discussion is carried out in a fair and respectful manner, possibly mitigating the effects of cross-cutting exposure on increasing cross-pressures. Hence, moderated equality can alleviate some negative influence of cross-cutting exposure on discursive rationality and civility, by intentionally providing participants with opportunities to be exposed to different opinions and reconsider the other side (Luskin, Fishkin, & Jowell, 2002).

Similar effects can be expected for the consequences of cross-cutting exposure on political participation and civic virtues. The rule of equality in deliberation can provide participants with an “equal opportunity to access political influence” (Knight & Johnson, 1997, p. 208). Throughout this process, people can retain their interest in the political outcomes relevant to the discussions and become less detached from political discourse even when they are exposed to oppositional viewpoints, eventually leading to greater motivation to engage in political decision-making (Cooper & Gulick, 1984; Roberts, 2004).

Further, with the equality rule being a procedural principle, participants may realize that cooperation with disagreeing others is not impossible (Laurian, 2009; Smith & Wales, 2000). When everyone—from the extreme naysayers to the ardent supporters of any given issue—earns equal respect, participants can appreciate the utmost norm of democracy: full inclusion of all voices (Abdullah et al., 2016). Active reflections through equality norms set in disagreeing situations can promote empathy for the preferences of other people (Morrell, 2010) and tolerance toward divergent viewpoints (Sullivan et al., 1993).

To the best of our knowledge, there is no previous research that empirically examined the influence of structured discussions among diverse but equal voices on deliberative qualities. While cross-cutting exposure alone may fail to decisively bring about positive outcomes, combining these two conditions can entail desirable outcomes in online spaces. In this regard, we set the following research questions:

RQ4, RQ5, RQ6: Does the implementation of the equality rule during the discussion on a gender issue moderate the effects of cross-cutting exposure on deliberativeness (rationality and civility) (RQ4), political participation in gender-related activities (RQ5), and civic virtues (empathy and tolerance) (RQ6)?

Methods

Experimental designs and procedures

The experiment involved moderated deliberations on the repeal of the abortion ban via KakaoTalk Open Chat that provides chatting not only with users’ intimate contacts but also with anonymous others. Using Open Chat features, we originally constructed our basic experimental design as presented in Table 1. The design was based on 1) different compositions of discussion participants in terms of their attitudes toward the abortion issue, i.e., whether the opinions favored pro-life, pro-choice, or were evenly distributed, and 2) whether the equality rule was applied. Groups were matched according to the participants’ attitudes toward the abortion ban (see Appendix A 1.2 pretest for details). In the pretest, participants rated their agreements on two statements: whether they (1) support for the abortion ban and (2) support for the lift of the abortion ban on a scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). After reverse-coding the measurement of the support for the abortion ban, we calculated the average for the final score from the two measurements (M = 2.99, SD = 1.45). People who had their final score above 3 were categorized as pro-lifers, whereas those with scores below 3 were classified as pro-choicers. Moderates who scored 3 were not included in the experiment.

The original experimental setting (N = 48).

| Opinion diversity within a group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 pro-choice, 6 pro-life | 4 pro-choice, 4 pro-life | 6 pro-choice, 2 pro-life | ||

| The rule of equality | No | Group 1 (n = 8) | Group 2 (n = 8) | Group 3 (n = 8) |

| Yes | Group 4 (n = 8) | Group 5 (n = 8) | Group 6 (n = 8) | |

Since opinion diversity was manipulated at the group level in our original experimental setting, the degree of cross-cutting exposure during group discussions varied among participants assigned to the same experimental conditions. For example, participants with a group-majority viewpoint (e.g., pro-lifers assigned to Group 1 in Table 1) and those who hold a group-minority viewpoint (e.g., pro-choicers assigned to Group 1 in Table 1) encountered different levels of dissonant perspectives while chatting because the opinion distribution of some groups was tilted toward a particular side (e.g., the pro-life side in Group 1 in Table 1).

To operationalize cross-cutting exposure as ego-centric diversity at the individual level, i.e., the level of disagreement one encounters during a group discussion, experimental groups were reconstructed after the post-test was completed (Table 2). For example, a pro-choicer in group 1 in the initial design, who was engaged in conversations with six pro-lifers and two pro-choicers out of eight participants, was reassigned to group 3 that had the highest level of cross-cutting exposure (i.e., six out of eight, thus 75%). As one-way ANOVA results in Appendix C indicate, there was no significant difference in major demographic and related political variables among the reconstructed groups, indicating that these groups were comparable.

The reconstructed experimental setting (N = 48).

| Cross-cutting exposure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25% | 50% | 75% | ||

| The rule of equality | No | Group 1 (n = 12) | Group 2 (n = 8) | Group 3 (n = 4) |

| Yes | Group 4 (n = 12) | Group 5 (n = 8) | Group 6 (n = 4) | |

-

Note. The percentage of cross-cutting exposure indicates the proportion of individuals holding different opinions that an individual encounters in a discussion group.

While most of the study participants were undergraduates from major universities in Seoul, South Korea, some robust supporters of the abortion ban, who were seldom found in the university student sample, were recruited from recently-held abortion-related rallies. The topic of discussion was whether South Korea should lift its abortion ban. The entire discussion session was limited to 30 minutes, and only the 30-minute length of the discussion after the facilitator’s opening statement was considered for the content analysis. To ensure informed deliberation, a ten-page document on the current state of the abortion issue and major arguments and rationales on each side were delivered to each participant a few days before discussion. All participants were given a mobile voucher worth 5,000 KRW (approximately $5) for participation. Each participant used a pseudonym assigned by the researcher as a nickname to maintain confidentiality during the discussion.

For all sessions, the facilitator announced the rules for discussion in the beginning (e.g., a 30-minute time limit) and regulated unpleasant language if needed. For the groups informed with the equality rule, the facilitator announced the predetermined order by which the participants should speak at least three times during discussion: at the beginning, in the middle (after 15 minutes from the start), and at the end. More specifically, participants in the groups where the rule of equality was enforced were shown the following messages three times during the discussion: “Now, please present your opinions about the discussed topic in the predetermined order: Frodo – Ryan – Neo – Jay-Z – Tube – Peach (names of Kakao characters). If you wish not to speak, you can say ‘no opinion.’”

Adapting the equality rule from Deliberative Polling (Fishkin, 2011), we manipulated it as guaranteeing opportunities to speak at least three times for all participants, rather than structuring the whole discussion in a determined order—which may be more effective in face-to-face settings—or mechanically equalizing the amount of time for each to speak. By providing at least three chances to talk about their arguments and reasons, we sought to equalize the quantity of given speech from the participants, to the extent that the equality rule does not demotivate them from freely exchanging their thoughts in online chats. As a result, the groups with the rule of equality showed lower standard deviation in the total number of utterances shared during the discussion session (M = 10.96, SD = 2.60), compared to the groups without the equality rule (M = 9.58, SD = 3.13). After a 30-minute discussion, a post-test questionnaire was administered.

Measures

The pretest questionnaire contained several items regarding demographic information and attitudes toward the abortion ban. Gender, ideological orientation, political interest, interest in gender issues, and political knowledge were measured and treated as control variables (see Appendix A 1.2 Pretest for details). The posttest questionnaire included items for participatory intentions toward gender-related political activities and empathy and tolerance for the other side (see Appendix A 1.3 Posttest for details). After the post-survey was completed, debriefing messages were disseminated to the participants.

Particularly, the deliberativeness of a political discussion was measured through a content analysis of the discussion scripts in the chat rooms from a total of 6 sessions. (See Appendix B for details.) Similar to the level of justification in the Discourse Quality Index (Bächtiger & Parkinson, 2019; Steenbergen et al., 2003), discursive rationality was operationalized as the number of reasons to support one’s argument stated in the discussion scripts. Here, reasons included a broad range of justifying statements such as declared facts, examples, statistics, experiences, and feelings (Jaidka et al., 2019; Oz et al., 2018; Stroud et al., 2015). On the other hand, civility was assessed by the sum of appeals to common interests and respect for opposing opinions (Bächtiger & Parkinson, 2019; Steiner et al., 2004). Showing respect for different opinions, suggesting solutions, building consensus, and recognizing commonality among opposing groups were all considered as civil acts (Steenbergen et al., 2003; Stroud et al., 2015).

Results

The study tested whether the conditions of deliberation, i.e., cross-cutting exposure and the equality rule moderated in discussions, meaningfully enhance the deliberative quality of discussion and promote gender-related political participation and civic attitudes.

Quality of Discussion: Deliberativeness (RQ1 & RQ4)

We explored whether encountering contrary opinions influences the deliberativeness of gender-related discussions (RQ1), and whether enforcing the rule of equal participation moderates the effects of cross-cutting exposure (RQ4). To test these inquiries, a series of analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) on rank-transformed measures1 were conducted. Table 3 summarizes the results. (See Appendix D for the results of ANCOVA without using rank-transformed measures. The results remain fairly the same.)

Effects of cross-cutting exposure and the rule of equality on the deliberativeness of abortion discussion.

| Rationality | Civility | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | F | η2 | p | df | F | η2 | p | |

| Cross-cutting exposure (A) | 2 | 0.96 | .05 | .393 | 2 | 1.11 | .06 | .342 |

| The rule of equality (B) | 1 | 5.08 | .12 | .030* | 1 | 2.25 | .06 | .142 |

| Interaction (AXB) | 2 | 3.24 | .15 | .050* | 2 | 2.50 | .12 | .096^ |

| Error (S/AB) | 37 | (166.82) | 37 | (184.72) | ||||

-

Note. Entries in parentheses refer to the mean square of error. Gender, political orientation, political interest, interest in gender issues, and political knowledge were treated as covariates.

** p ≤ .01 * p ≤ .05 ^ p ≤ .1.

Results for RQ1 indicate that the effects of cross-cutting effects on deliberativeness were limited; cross-cutting exposure did not entail a significant increase in rationality, F (2, 37) = 0.96, p = .393, or in civility, F (2, 37) = 1.11, p = .342.

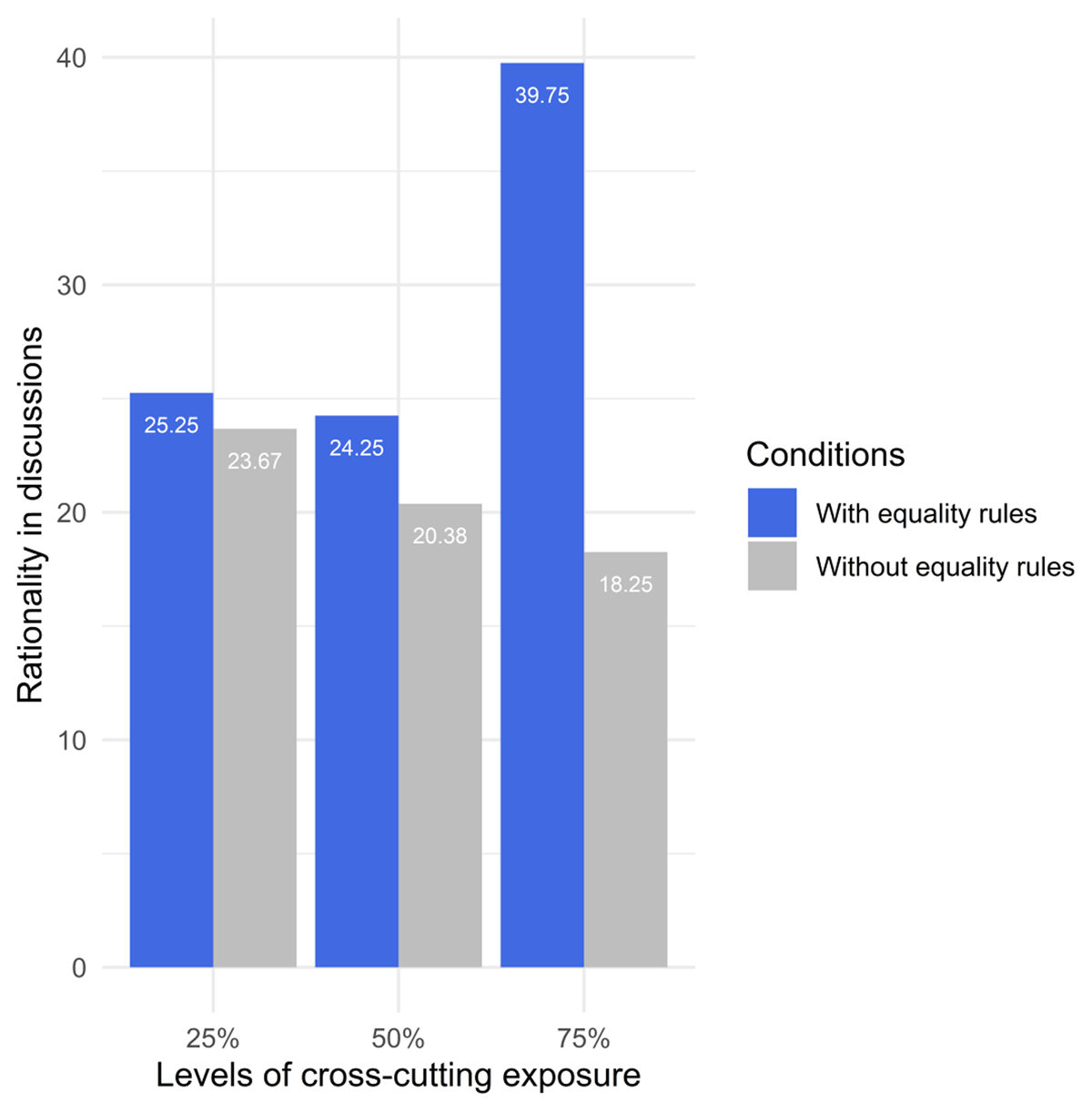

On the other hand, the effects of interaction between the level of egocentric diversity and the provision of equal chances of speaking (RQ4) were found modestly significant for the deliberative qualities of the discussion. Positive effects of the rule of equality on rationality were most prominent when the level of cross-cutting exposure was the highest, while the effects were reduced in more homogeneous conditions, F (2, 37) = 3.24, p = .050, as shown in Figure 1. People with a higher level of cross-cutting exposure were much more likely to provide justifications for their arguments during the discussion when the equality rule was applied. Applying the equality rule increased civility in a similar pattern, albeit marginally significant, for the participants in the highly discordant context, F (2, 37) = 2.50, p = .096.

Outcomes of Deliberation: Political Participation (RQ2 &RQ5) and Civic Virtues (RQ3 & RQ6)

We investigated whether exposure to opposing opinions toward the abortion issue and application of the rule of equality in such discordant settings can influence gender-related participation and civic virtues such as empathy and tolerance toward the opposing parties. The results are summarized in Table 4.

Effects of cross-cutting exposure and the rule of equality on political participation and civic virtues.

| Political participation in gender-related activities | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | F | η2 | p | |||||

| Cross-cutting exposure (A) | 2 | 0.33 | .02 | .724 | ||||

| The rule of equality (B) | 1 | 5.04 | .12 | .031* | ||||

| Interaction (AXB) | 2 | 4.56 | .20 | .017* | ||||

| Error (S/AB) | 37 | (134.90) | ||||||

| Civic virtues | ||||||||

| Empathy | Tolerance | |||||||

| df | F | η2 | p | df | F | η2 | p | |

| Cross-cutting exposure (A) | 2 | 6.50 | .26 | .004** | 2 | 0.69 | .04 | .510 |

| The rule of equality (B) | 1 | 0.10 | .003 | .755 | 1 | 1.29 | .03 | .264 |

| Interaction (AXB) | 2 | 0.06 | .003 | .944 | 2 | 0.63 | .03 | .538 |

| Error (S/AB) | 37 | (167.51) | 37 | (167.85) | ||||

-

Note. Entries in parentheses refer to mean square of error. Gender, political orientation, political interest, interest in gender issues, and political knowledge are treated as covariates.

** p ≤ .01 * p ≤ .05 ^ p ≤ .1.

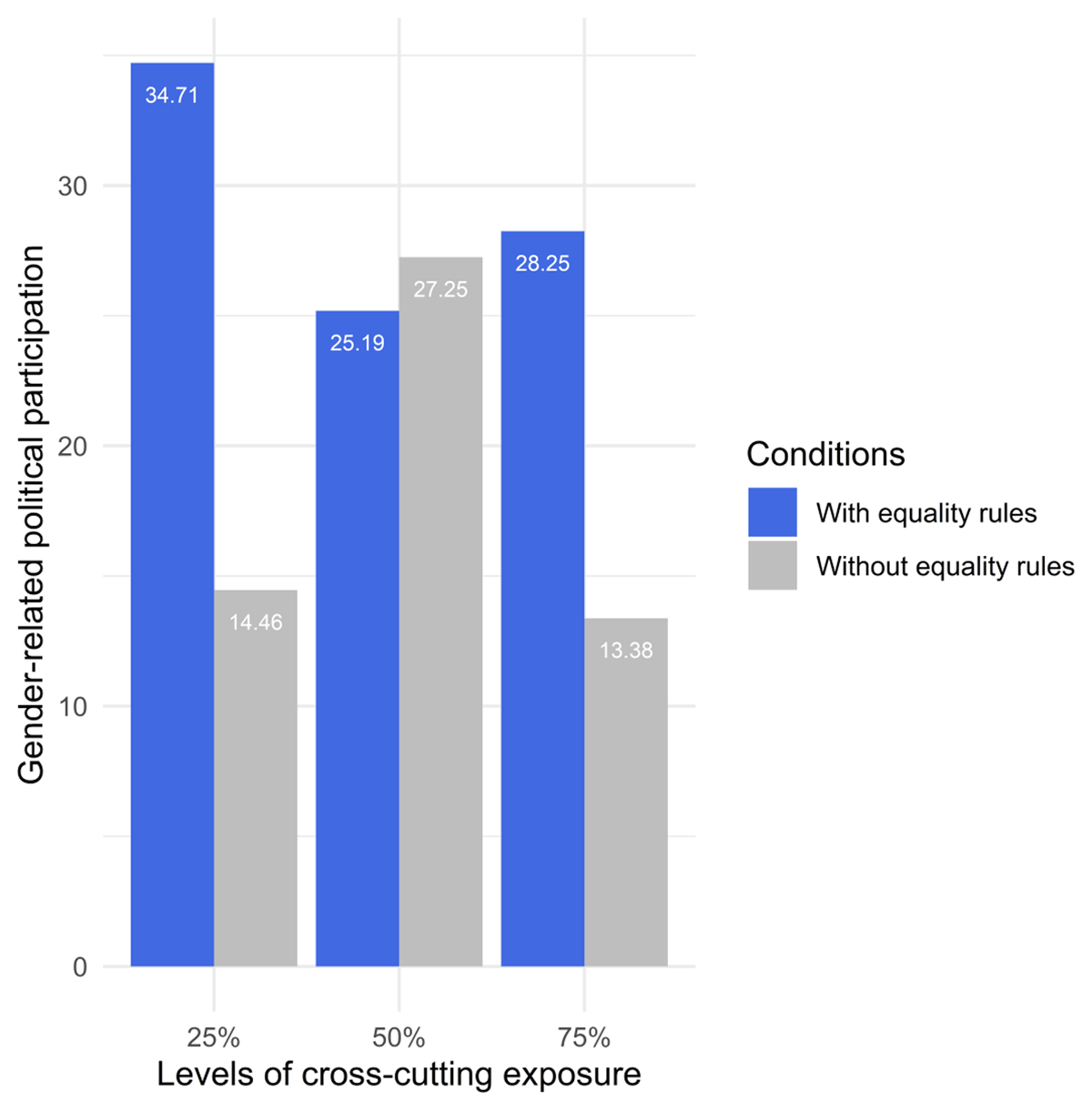

RQ2, which deals with the effect of cross-cutting exposure on political participation with regard to gender issues, did not entail any directional findings. Hearing the other side on the abortion issue did not significantly promote nor undermine political activism. On the other hand, the effects of interaction between the two deliberative conditions on political participation (RQ5) were statistically significant, F (2, 37) = 4.56, p = .017. While cross-cutting exposure itself did not meaningfully enhance political participation, the enforcement of the equality rule increased participatory intentions for gender politics among the people who have the highest level of egocentric diversity (i.e., 75%), as illustrated in Figure 2. That is, when equal chances to speak are guaranteed, people on the minority side were more motivated to participate than otherwise. However, a similar pattern was also found among the people whose cross-cutting exposure was the lowest (i.e., 25%), indicating that the equality rule encouraged discussants to participate in gender-related issues more actively when there was a more dominant opinion within a discussion group.

Results for RQ3, regarding the improvement in civic virtues through cross-cutting exposure, did not support the normatively assumed benefits of deliberation. Although cross-cutting exposure influenced empathy, F (2, 37) = 6.50, p = .004, the direction appeared reversed: individuals who belonged to the conditions with the lowest level of cross-cutting exposure (M = 30.98, SD = 11.97) expressed a higher level of empathy than those exposed to the highest level of opinion dissimilarity (M = 16.88, SD = 6.60). Effects of the rule of equality on moderating the influence of cross-cutting exposure in enhancing one’s empathy and tolerance (RQ6) were not found significant, either.

Discussion

We explored how some of the key normative conditions from deliberation theory can promote empirical benefits in the context of conflictual discussion over a gender issue via an online messaging application. Several research questions regarding the effects of cross-cutting exposure and the rule of equality on 1) the deliberativeness of gender-issue discussions, 2) participation in gender-related political activities, and 3) civic virtues such as empathy and tolerance and were proposed.

Experiencing a higher level of disagreement did not automatically transfer to a better quality of political discussion. However, the equality rule functioned as an important moderator: A greater level of cross-cutting exposure led to a higher level of rationality when the rule of equality was enforced. Individuals were more eager to deliver their arguments with the reasons that are relevant to the issue when equal opportunities to deliver their opinion were given. Further, our findings suggest that benefits from the interaction of the two aforementioned conditions are largely driven by the discussants exposed to the greatest level of disagreement while speaking. The equality rule helped these discussants argue with others in a more rational way. In this sense, a structured intervention to provide equal chances to speak for everyone may be crucial in relatively mixed-opinion interactions for ensuring participants, especially those who hold minority opinions, that they are being treated as reasonable discussants in a fair manner.

When the participants experience disagreement, they may react in two different ways: they would either actively persuade others on plausible grounds or rather remain silent or indifferent. When the other parties’ opinion is deemed as the majority and the discussed issues are socially controversial, the latter scenario seems more compelling (Noelle-Neumann, 1993; Scheufele & Eveland Jr, 2001). Once we take these complex possibilities into consideration, the next step is to address exactly how to transform hostile discussions into deliberative exchange of ideas encompassing reasonable arguments and mutual respect. Our experiment showed that the rule of equality in cross-cutting interactions rewarded participants with more logical expression, rather than making them retreat from mutual interaction. Thus, we conclude that providing equal opportunities to speak may be essential, especially for those holding minority opinions, to overcome feeling reluctant to talk to others who disagree with them.

Similar patterns arose regarding political participation related to gender issues. As stated in a recent meta-analysis (Matthes et al., 2019), the experience of political difference did not directly influence how much people participated in gender-related political activities. However, when the equality rule was additionally enforced, motivation to participate increased among those who were engaged in gender-related discussions either as a minority or as a majority. First, the groups exposed to the highest level of disagreement (i.e., 75%) may have solidified their rational grounds to argue against the majority’s opinion (i.e., heightened rationality in speaking) and felt more need to take action for their own political beliefs when they are given equal chances to speak. On the other hand, the groups assigned to the lowest level of cross-cutting exposure (i.e., 25%) may have experienced a greater level of social acceptance for their opinion through the equality rule. However, these interpretations are only tentative for now and should be subjected to future investigation.

For civic virtues, the role of the equality rule was found limited; it did not appear as a critical moderator for the effects of hearing the other side. Whereas encountering conflicting opinions decreased empathy toward the opposing side and failed to cultivate tolerance for disagreement, additionally enforcing the rule of equality did not make any meaningful changes.

While academics have long debated on the extent to which cross-cutting exposure is normatively meritorious (e.g., Mutz, 2006), we focused on the interactions of the two essential conditions for deliberation and demonstrated that the providing equal opportunities for speech in cross-cutting online discussions can be vital to minimize the gap between deliberative ideals and actual political outcomes. This finding is highly relevant to the current landscape of gender politics in South Korea where inter-gender dialogue is becoming extremely heated and polarized especially in online contexts. Our findings suggest that online deliberative interventions could be a productive solution for the hostilities surrounding gender issues. Applying the rule of equality in the exchange of opposing viewpoints may function as a starting point for individuals to transform themselves into more reasoning, respecting, and participating citizens.

This study is not without limitations. We did not precisely illuminate the possible mediating process in which the key deliberation conditions influence democratic outcomes through the deliberativeness of political discussion. Furthermore, our sample displayed a relatively high level of interest in gender issues (M = 4.52, SD = 1.15). That is, people highly interested in gender issues might have chosen to participate in this experiment, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings. Still, the characteristic of our subjects reflects the involved-yet-divided public over gender issues in South Korea. More than 70% of people in their 20s in South Korea are highly interested in gender issues (Korean Women’s Development, 2019), and more than half of them have indicated gender conflict as the most unsolvable problem (Kim, 2019). Given that most of the online discourse is being dominated by those highly involved in gender issues but antagonistic toward the opposing groups, our findings illuminate the importance of intervening efforts to transform such inimical conversations into a deliberative discussion. It is also fair to say that the main purpose of this study was to explore relatively open inquiries on the interaction of cross-cutting exposure and the rule of equality rather than to confirm some directional relationships. The external validity of our exploratory findings can be improved through future replications with non-student samples.

The equality rule in an online deliberation should be more conceptually refined and contextualized. There is a possibility that the equality rule in online settings might backfire because it is unnatural in online settings. From debriefing sessions, we also found that it is necessary to consider the unique characteristics of a given online platform in enforcing specific rules for deliberation. Another remaining question pertains to a more theoretical issue, namely, the desirable degree of cross-cutting exposure. The limited effects of cross-cutting exposure observed in this study may be due to the vague explication of the desirable level of hearing the other side. In this sense, more studies should be ensued to identify the optimal level of diversity one should encounter during a political discussion.

Data Accessibility Statement

Supplementary file 1: The data related to the experiments and the content analysis.

Supplementary file 2: The questionnaire, coding instructions for a content analysis, and results for the supplemental analysis.

The data reported in this paper and additional supplementary materials, including the questionnaire, coding instructions for a content analysis, and results for supplemental analyses, can be found in each link. The supplementary files have also been cited in the main text.

Notes

- We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers who suggested to use ANCOVA on ranks to address the problem of having a small sample size in our study. ⮭

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

1 Abdullah, C., Karpowitz, C. F., & Raphael, C. (2016). Equality and equity in deliberation: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Public Deliberation, 12(2), 1. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.253

2 Albrecht, S. (2006). Whose voice is heard in online deliberation?: A study of participation and representation in political debates on the internet. Information, Community and Society, 9(1), 62–82. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/13691180500519548

3 Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison–Wesley.

4 Bächtiger, A., & Parkinson, J. (2019). Mapping and measuring deliberation: towards a new deliberative quality. Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199672196.001.0001

5 Barabas, J. (2004). How deliberation affects policy opinions. American Political Science Review, 98(4), 687–701. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055404041425

6 Besley, J. C., & McComas, K. A. (2005). Framing justice: Using the concept of procedural justice to advance political communication research. Communication Theory, 15(4), 414–436. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2005.tb00342.x

7 Bettencourt, B. A., & Dorr, N. (1998). Cooperative interaction and intergroup bias: Effects of numerical representation and cross-cut role assignment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(12), 1276–1293. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/01461672982412003

8 Coleman, S., & Gøtze, J. (2001). Bowling together: Online public engagement in policy deliberation. Hansard Society London.

9 Cooper, T. L., & Gulick, L. (1984). Citizenship and professionalism in public administration. Public Administration Review, 44, 143–151. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/975554

10 Eliasoph, N. (1998). Avoiding politics: How Americans produce apathy in everyday life. Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511583391

11 Elster, J. (1998). Deliberative democracy (J. Elster, Ed.). Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139175005

12 Esterling, K. M., Fung, A., & Lee, T. (2015). How much disagreement is good for democratic deliberation? Political Communication, 32(4), 529–551. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2014.969466

13 Fishkin, J. S. (1995). The voice of the people: Public opinion and democracy. Yale University Press.

14 Fishkin, J. S. (2011). When the people speak: Deliberative democracy and public consultation. Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199604432.001.0001

15 Friess, D., & Eilders, C. (2015). A systematic review of online deliberation research. Policy & Internet, 7(3), 319–339. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.95

16 Gastil, J. (2006). How balanced discussion shapes knowledge, public perceptions, and attitudes: A case study of deliberation on the Los Alamos National Laboratory. Journal of Public Deliberation, 2(1). DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.38

17 Gastil, J., Deess, E. P., & Weiser, P. (2002). Civic awakening in the jury room: A test of the connection between jury deliberation and political participation. The Journal of Politics, 64(2), 585–595. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2508.00141

18 Grönlund, K., Herne, K., & Setälä, M. (2015). Does enclave deliberation polarize opinions? Political Behavior, 37(4), 995–1020. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-015-9304-x

19 Gutmann, A., & Thompson, D. (1996). Democracy and disagreement. Harvard University Press.

20 Habermas, J. (1989). The structural transformation of the public sphere. MIT Press.

21 Hovland, C. I., Janis, I. L., & Kelley, H. H. (1954). Communication and persuasion: Psychological studies of opinion change. Yale University Press.

22 Huckfeldt, R., Mendez, J. M., & Osborn, T. (2004). Disagreement, ambivalence, and engagement: The political consequences of heterogeneous networks. Political Psychology, 25(1), 65–95. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00357.x

23 Jaidka, K., Zhou, A., & Lelkes, Y. (2019). Brevity is the soul of twitter: The constraint affordance and political discussion. Journal of Communication, 69(4), 345–372. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqz023

24 Jeong, E., & Lee, J. (2018). We take the red pill, we confront the DickTrix: Online feminist activism and the augmentation of gendered realities in South Korea. Feminist Media Studies, 18(4), 705–717. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1447354

25 Kim, H.-Y. (2019, January 2). Class and gender conflicts increase explosively. Hankook Ilbo. Retrieved from https://www.hankookilbo.com/News/Read/201812270601327645?did=NA&dtype=&dtypecode=&prnewsid=.

26 Klofstad, C. A., Sokhey, A. E., & McClurg, S. D. (2013). Disagreeing about disagreement: How conflict in social networks affects political behavior. American Journal of Political Science, 57(1), 120–134. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2012.00620.x

27 Knight, J., & Johnson, J. (1997). What sort of equality does deliberative democracy require? (J. Bohman & W. Rehg, Eds.). MIT Press.

28 Korean Women’s Development. (2019). Korean women’s development institute: Survey reports on perceptions of gender equality issues in South Korea. Retrieved from http://www.kwdi.re.kr/publications/kwdiBriefView.do?p=1&idx=122966.

29 Larmore, C. (1990). Political liberalism. Political Theory, 18(3), 339–360. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0090591790018003001

30 Laurian, L. (2009). Trust in planning: Theoretical and practical considerations for participatory and deliberative planning. Planning Theory & Practice, 10(3), 369–391. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/14649350903229810

31 Luskin, R. C., Fishkin, J. S., & Jowell, R. (2002). Considered opinions: Deliberative polling in Britain. British Journal of Political Science, 32(3), 455–487. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123402000194

32 MacKuen, M. B., Wolak, J., Keele, L., & Marcus, G. E. (2010). Civic engagements: Resolute partisanship or reflective deliberation. American Journal of Political Science, 54(2), 440–458. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00440.x

33 Manin, B. (1987). On legitimacy and political deliberation. Political Theory, 15(3), 338–368. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0090591787015003005

34 Matthes, J., Knoll, J., Valenzuela, S., Hopmann, D. N., & Von Sikorski, C. (2019). A meta-analysis of the effects of cross-cutting exposure on political participation. Political Communication, 36(4), 523–542. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2019.1619638

35 McLeod, J. M., Scheufele, D. A., Moy, P., Horowitz, E. M., Holbert, R. L., Zhang, W., Zubric, S., & Zubric, J. (1999). Understanding deliberation: The effects of discussion networks on participation in a public forum. Communication Research, 26(6), 743–774. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/009365099026006005

36 Meffert, M. F., Guge, M., & Lodge, M. (2004). Good, bad, and ambivalent: The consequences of multidimensional political attitudes (W. E. Saris & P. M. Sniderman, Eds.). Princeton University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9780691188386-005

37 Mendelberg, T. (2002). The deliberative citizen: Theory and evidence (M. X. Delli Carpini, L. Huddy, & R. Shapiro, Eds.). JAI Press.

38 Mill, J. S. (2015). On liberty, utilitarianism, and other essays (2nd Ed.; M. Philp & F. Rosen, Eds.). Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1958). DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/owc/9780199670802.001.0001

39 Morrell, M. E. (1999). Citizen’s evaluations of participatory democratic procedures: Normative theory meets empirical science. Political Research Quarterly, 52(2), 293–322. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/106591299905200203

40 Morrell, M. E. (2010). Empathy and democracy: Feeling, thinking and deliberation. Penn State University Press.

41 Moy, P., Domke, D., & Stamm, K. (2001). The spiral of silence and public opinion on affirmative action. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 78(1), 7–25. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/107769900107800102

42 Mutz, D. C. (2002). Cross-cutting social networks: Testing democratic theory in practice. American Political Science Review, 96(1), 111–126. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055402004264

43 Mutz, D. C. (2006). Hearing the other side: Deliberative versus participatory democracy. Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511617201

44 Mutz, D. C. (2008). Is deliberative democracy a falsifiable theory? Annual Review of Political Science, 11, 521–538. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.081306.070308

45 Noelle-Neumann, E. (1993). The spiral of silence: Public opinion, our social skin. University of Chicago Press.

46 Ock, H.-J. (2019, March 31). Debate on abortion ban intensifies as decision looms. The Korea Herald. Retrieved from http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20190331000068.

47 Oz, M., Zheng, P., & Chen, G. M. (2018). Twitter versus Facebook: Comparing incivility, impoliteness, and deliberative attributes. New Media & Society, 20(9), 3400–3419. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817749516

48 Papacharissi, Z. (2004). Democracy online: Civility, politeness, and the democratic potential of online political discussion groups. New Media & Society, 6(2), 259–283. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1461444804041444

49 Park, S.-G. (2000). The significance of civility in deliberative democracy. Korean Journal of Journalism & Communication Studies, 53(3), 173–197.

50 Realmeter. (2017, November). TBS survey results: Public opinion on abortion ban (rep.).

51 Roberts, N. (2004). Public deliberation in an age of direct citizen participation. The American Review of Public Administration, 34(4), 315–353. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0275074004269288

52 Robinson, C. (2010). Cross-cutting messages and political tolerance: An experiment using evangelical protestants. Political Behavior, 32(4), 495–515. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9118-9

53 Roh, S., & Min, Y. (2009). The coexistence of “deliberation” and “participation”: The moderating effects of deliberative political dialogue on the relationships between cross-cutting exposure and political participation. Korean Journal of Journalism & Communication Studies, 53(3), 173–197.

54 Scheufele, D. A., & Eveland, W. P. Jr. (2001). Perceptions of ‘public opinion’ and ‘public’ opinion expression. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 13(1), 25–44. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/13.1.25

55 Scheufele, D. A., Hardy, B. W., Brossard, D., Waismel-Manor, I. S., & Nisbet, E. (2006). Democracy based on difference: Examining the links between structural heterogeneity, heterogeneity of discussion networks, and democratic citizenship. Journal of Communication, 56(4), 728–753. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00317.x

56 Smith, G., & Wales, C. (2000). Citizens’ juries and deliberative democracy. Political Studies, 48(1), 51–65. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.00250

57 Song, H., & Eveland, W. P. Jr. (2015). The structure of communication networks matters: How network diversity, centrality, and context influence political ambivalence, participation, and knowledge. Political Communication, 32(1), 83–108. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2014.882462

58 Steenbergen, M. R., Bächtiger, A., Spörndli, M., & Steiner, J. (2003). Measuring political deliberation: A discourse quality index. Comparative European Politics, 1(1), 21–48. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.cep.6110002

59 Steger, I. (2016, October 24). An epic battle between feminism and deep-seated misogyny is under way in South Korea. Quartz. Retrieved from https://qz.com/801067/an-epic-battle-between-feminism-and-deep-seated-misogyny-is-under-way-in-south-korea.

60 Steiner, J., Bächtiger, A., Spörndli, M., & Steenbergen, M. (2004). Deliberative politics in action: Cross-national study of parliamentary debates. Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511491153

61 Stroud, N. J., Scacco, J. M., Muddiman, A., & Curry, A. L. (2015). Changing deliberative norms on news organizations’ Facebook sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20(2), 188–203. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12104

62 Sullivan, J. L., Piereson, J., & Marcus, G. E. (1993). Political tolerance and American democracy. University of Chicago Press.

63 Sunstein, C. R. (2002). The law of group polarization. Journal of Political Philosophy, 10(2), 175–195. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9760.00148

64 Thompson, D. F. (2008). Deliberative democratic theory and empirical political science. Annual Review of Political Science, 11, 497–520. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.081306.070555

65 Vinokur, A., & Burnstein, E. (1978). Depolarization of attitudes in groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36(8), 872–885. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.36.8.872

66 Wojcieszak, M. (2011). Deliberation and attitude polarization. Journal of Communication, 61(4), 596–617. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01568.x

67 Zhang, W. (2015). Perceived procedural fairness in deliberation: Predictors and effects. Communication Research, 42(3), 345–364. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0093650212469544