Introduction

In the current time of democratic crisis, with declining rates of voter participation, political disaffection of citizens and the rise of national populism, many deliberative democrats increasingly promote the use of so-called deliberative minipublics where citizens discuss policy issues on the basis of good arguments in an atmosphere of mutual respect.1 This is usually associated with the promising idea that involving citizens in such kinds of democratic innovations will boost the legitimacy of democratic decision-making (Fishkin 2009, 2018; Smith 2009; Dryzek et al. 2019). At the same time, the question has come to the fore what deliberative forums actually can and should contribute to the broader deliberative system, and it has also been pointed out that such forums perform fairly badly in terms of participation rates and visibility. This has led many scholars to consider appropriate places for deliberative forums within the larger deliberative system (Lafont 2015; Mansbridge et al. 2012; Chambers 2009; Parkinson 2006).

This article addresses three main issues of this theoretical discussion. A first question concerns the authority that deliberative forums should have in political decision-making. While some advocates call for strong authorization including the idea that deliberative forums should make binding decisions (e.g., Buchstein 2019), the majority of deliberative democrats see the role of deliberative forums as purely advisory. The philosopher Cristina Lafont (2015, 2017, 2019) has been prominent in radically challenging the idea of granting strong authorization powers to deliberative forums. She forcefully argues that deliberative forums reach conclusions for reasons that most ordinary voters who have not gone through the deliberative experience are not likely to accept: ‘many [non-deliberating citizens] will find out that the majority of the sample is not like them, since they actually oppose their view, values and policy objectives on the issue in question’. This will be especially the case, claims Lafont, when issues are highly salient and controversial, making agreement among citizens highly improbable. Hence, deliberative forums should not be conferred direct decision-making powers; the best they can do is to provide input into a democratic system which then needs to be processed and deliberated further (Lafont 2017). Second, it is an open question whether citizens themselves would perceive such a legitimacy problem. What we do know from empirical research is that legitimacy perceptions of participants increase when they take part in deliberative forums (e.g., Christensen et al. 2017; Grönlund et al. 2010). What we do not know, however, is how and under what conditions non-participating citizens would judge the legitimacy of deliberative forums. According to Lafont, only the latter question is apt to shed light on her critique empirically.2 Finally, a critical point is the limited visibility of deliberative forums to the wider public (Rummens 2016). Very few citizens are aware of deliberative forums and even fewer know how they work internally (e.g., Fournier et al. 2011; Clauwaerts & Reuchamps 2018). As such, we may tap into non-attitudes when we simply ask non-participants whether and under what conditions they perceive deliberative forums as legitimate; moreover, Lafont’s challenge of a legitimacy deficit is persuasive only if citizens are aware of such procedures and have thought through their democratic implications.

This article mainly engages with Lafont’s argument, as it is the most forceful and novel theoretical critique of deliberative forums. Empirically, it reports on an explorative study of how deliberative forums should be designed in order to boost their perceived legitimacy among non-participants. The conjoint experiment represents one of first studies to test different authorization mechanisms (ranging from pure recommendations to binding decisions) and a wide variety of institutional design elements of deliberative forums (e.g., Farrell et al. 2019). This allows for testing the importance of authorization mechanisms under randomly varied conditions. Recently, Christensen (2020) has conducted a similar experiment on legitimacy perceptions of participatory processes in general, but with fewer authorization mechanisms as well as fewer institutional design features that are critical from both a theoretical and practical vantage. Furthermore, this experiment is the first study to connect different authorization mechanisms and design elements of deliberative forums with other sources of legitimation such as issue salience and non-participants’ substantive policy preferences (Esaiasson et al. 2016; Marien and Kern 2018). Most importantly, this experiment is also the first to provide participants with an information component on the advantages and disadvantages of specific design features of deliberative forums. Given the visibility and awareness gap of deliberative forums among the wider citizenry, this is a crucial part of validating legitimacy perceptions.

The experiment was conducted at the University of Stuttgart in May 2019, with 167 students. Of course, students are not representative of the citizenry, and the experiment thus may lack external validity. Paradoxically, however, students fulfill one crucial criterion, namely that most of them have a higher awareness of deliberative forums. Given students’ generally superior reflective capacities for thinking through abstract issues, we can test as a proper counterfactual how non-participants would judge the legitimacy of deliberative forums if they were fully informed about the various design features, including authorization mechanisms. The results of the conjoint experiment provide the first empirical insights into a largely theoretical discussion, namely, what roles deliberative forums should have in the eyes of non-participants. They show that respondents of the experiment want the authority of deliberative forums to be clearly circumscribed and minimal. Further, the experiment takes into account different design features that are frequently discussed in the context of deliberative forums. The results indicate that respondents of the experiment not only support the recommendatory character of deliberative forums, but also place a strong emphasis on the representativeness and inclusiveness of such forums. Moreover, legitimacy evaluations are also closely tied to issue salience and substantive considerations. Finally, their awareness of deliberative forums substantially affects respondents’ legitimacy perceptions, emphasizing the importance of providing information about deliberative forums’ design and functioning.

The paper proceeds as follows. It first sketches the ongoing normative debate about the legitimacy of deliberative forums, with a prime focus on their authorization. Next, it proposes taking a bottom-up approach to the legitimacy of deliberative forums and connects this with non-participants’ procedural and substantive views as well as with the role of visibility. This is followed by a description of the conjoint experiment and the presentation of the results. The paper concludes by outlining some avenues for further research.

The Contested Role of Deliberative Forums: A Bottom-up Approach to Gauge Legitimacy

In representative democracies, the authorization of political power is legitimized by free, equal and universal election of political parties and people. At the same time, we are confronted with a decline in voter turnout, party membership and trust in representative institutions, as well as a perceived lack of accountability and responsiveness among elected representatives. Critics increasingly raise doubts about whether elections still fulfil their legitimizing function in democracies. Some even envision an ‘end of politicians’ (Hennig 2017), and make a case for replacing elections with forums of representatively selected lay citizens (van Reybrouck 2016) or institutionalized so-called ‘legislation by lot’ (Gastil and Wright 2019). These are indications of how debates about democratic legitimacy have shifted towards other forms of political participation and democratic self-government. An ongoing debate concerns the role that deliberative forums should play within a participatory society (Chambers 2009; Pateman 2012); or to put it more provocatively: how much power should be given to deliberative forums?

To date, the debate about the democratic roles of unelected, randomly selected groups of ordinary citizens has frequently boiled down to the question of ‘whether or not a mini-public makes binding decisions for the polity’ (Bächtiger et al. 2018: 16). In practice, however, deliberative forums usually just advise political decision-makers. Some theorists advocate for a strong authorization of deliberative forums. Hubertus Buchstein (2019), for instance, has recently argued that deliberative forums should not only work as ‘experiments’ for civic education, but should be authorized to make binding political decisions. According to Buchstein, participants in deliberative forums could develop a sort of participatory ‘motivation problem’ if they recognize that their participation is not consequential. Others have argued against any strong authorization of deliberative forums. In her recent work, Cristina Lafont (2015, 2017, 2019) makes one of the most radical critiques of deliberative forums. She fundamentally questions whether citizen deliberation should influence democratic decision-making at all. On her account, citizen deliberation is democratically illegitimate, since only a few (even if randomly selected) citizens are involved in determining political decisions for other citizens without being directly accountable to them (like political representatives in elections). According to Lafont, participants in deliberative forums do not live up to the claim that ‘they are people like me’, since non-participating citizens simply do not know what their opinions and choices would have been if they had deliberated themselves. Hence, if both citizens and political authorities accept recommendations from deliberative forums as a shortcut for their own decision-making, then this ‘blind deference’ is distinctly non-democratic. Others argue, however, that taking shortcuts might be very useful, particularly in complex governance systems where most citizens lack the resources to fully engage with political debates (Warren and Gastil 2015; Bächtiger and Goldberg 2020). In Lafont’s view, the only road to better outcomes is the long, participatory road that is taken when citizens forge a collective will by changing one another’s hearts and minds (Lafont 2019). To be sure, Lafont does not make a principled argument against deliberative forums. In a recent update of her critique, she suggests that deliberative forums may still produce ‘added value’ for a democratic system. This happens when they contest the majority opinion of the population and send a signal to the population about how an informed citizenry would think and decide; when they play a vigilant role by alerting political bodies that popular opinions are being ignored; or when they anticipate issues that are ignored by the wider public. However, while deliberative forums can have a useful ‘deliberation-promoting’ function they should not be given a ‘decision-making’ function.

Having outlined the ongoing normative debate on the legitimacy of deliberative forums, let us now turn to equally essential legitimacy issues, especially how citizens perceive and evaluate the contribution of deliberative forums to democratic systems. The starting point in this study is the assumption that democratic legitimacy involves both a normative dimension of the justification of democratic rule and an empirical dimension of the acceptance of the exercise of power by the people. While much discussion about the legitimacy of deliberative forums focuses on the normative dimension, the literature on the empirical dimension is surprisingly scarce. In asking what citizens expect from deliberative forums, perception-based approaches to democratic legitimacy are needed. This article employs a bottom-up approach to gauge democratic legitimacy by considering different authorization mechanisms (the core of theoretical debate) and design features of deliberative forums, but also emphasizes citizens’ awareness (experience with and information about deliberative forums). Now, we simply do not know how citizens, and particularly non-participating citizens (being at the heart of Lafont’s critique), view both the challenges and the refinements to the legitimacy perceptions of deliberative forums. This paper represents one of the first attempts to study this question empirically.3 It proceeds in three steps. First, it draws from the procedural fairness framework (e.g., Tyler 2011) in claiming that the degree of perceived legitimacy depends on how decisions are made (Tyler 1988; Tyler & Blader 2003; Tyler 2006). The key focus here is on authorization mechanisms (e.g., whether or not a deliberative forum makes binding decisions) but also includes other design features (such as recruitment and group size) of deliberative forums. We should not ignore the possibility that citizens also consider other characteristics important for their legitimacy perceptions, especially because deliberative forums are novel and unfamiliar institutions (a point that will be addressed further below). Since perceived legitimacy does not only depend on procedural aspects, this paper complements the procedural fairness framework with a substantive dimension, involving issue salience and ‘outcome favourability’ (i.e., whether the substantive outcomes of deliberative forums conform to the substantive policy preferences of non-participants). Finally, the paper assumes that research on the legitimacy perceptions of deliberative forums may tap into ‘non-attitudes’, since the design of such forums is beyond the experience of most citizens. It thus adds an information component to the experimental design, whereby participants are presented with pro and con arguments regarding specific design features of deliberative forums, including Lafont’s general critique of such forums.

Authorization Mechanisms and Design Elements of Deliberative Forums

The institutional setup and the authorization of deliberative forums can vary considerably in the real world, and this may affect non-participants’ legitimacy considerations: for instance, while some deliberative forums entail random selection with a large number of citizens, other involve a very small number of self-selected citizens. Regarding authorization mechanisms, most deliberative forums do not entail any commitment for political decision-makers. An example is the G1000 Citizens Summit Belgium, which was organized via grassroots organizations but only induced limited impact on public policy. In Germany, most deliberative forums are top-down, and at the local level only have a largely unspecified linkage to political decision-making. There are, however, also examples of a stronger commitment. The Citizens’ Assembly on Electoral Reform in British Columbia, for instance, drafted a proposal for a new electoral system that was subsequently submitted to a referendum (to which the government of British Columbia had committed itself). Similarly, proposals of Citizens’ Assemblies in Ireland on same-sex marriage and abortion were also put to a subsequent referendum. Moreover, in a few municipalities in Poland, recommendations based on citizen deliberation are implemented as soon as a certain number of participants have agreed to the proposal. In the case of Gdansk, recommendations that receive more than 80% agreement among participants are implemented. Finally (although hypothetical so far), deliberative forums could also produce binding decisions where citizens in a deliberative forum are formally empowered to make decisions.

Regarding the ‘authorization part’, this paper distinguishes between four possible authorization mechanisms of deliberative forums, adapted to the practices in the German context.4 First, participants work out a non-binding recommendation, which is then processed by the responsible administrative staff and politicians (recommendation with subsequent editing). Second, participants also work out a recommendation for the broader public, which is not processed further by the administrative staff and politicians (recommendation without subsequent editing). Third, participants work out a recommendation, which is subsequently put to a referendum (direct-democratic vote). Finally, proposals can also be accepted without further processing, i.e., the participants make decisive choices (binding decisions).

Besides authorization mechanisms, deliberative forums have additional institutional design features (for a recent overview see Farrell et al. 2019) that may affect non-participants’ legitimacy perceptions. Caluwaerts and Reuchamps (2018), for instance, find for a deliberative forum in Belgium that non-participating citizens do not automatically endorse decisions of the forum. Much depends on the design of the deliberative forum, e.g., who participated and how participants interacted in the forum. This paper focuses, first of all, on the recruitment of participants (random selection vs. self-selection), the size of the forum (large vs. small number of participants), and the group composition (inclusion or exclusion of political actors). Second, it includes aspects of how participants interact in the forum, including the dialogue format (face-to-face vs. online), and the level of consensus within the forum (clear vs. tight decisions). Table 1 provides an overview of the various design features of deliberative forums, including issue salience and ‘outcome favorability’ (see next section). Certainly, this list is not exhaustive; rather it is based on the practical significance of the attributes and their importance for non-participating citizens in the German context. Moreover, there is also a limit to how many design features can be presented to participants in a conjoint experiment (see below).

Design features of deliberative forums.

| Attribute | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Authorization | Recommendation without subsequent editing, recommendation with subsequent editing, recommendation with subsequent referendum, binding decision |

| Recruitment | Random selection, self-selection |

| Group size | Large (500), medium (100), small (20) |

| Composition | Citizen only, mixed group (citizens and officials) |

| Dialogue format | Face-to-face discussion, online discussion |

| Level of Consensus | close majority vote (52%), clear majority vote (64%), vast majority vote (88%) |

| Decision | For, against |

| Issue5 | High salience, low salience |

How do these design criteria and authorization mechanisms in particular affect legitimacy perceptions? Since research on this topic is in its infancy, the objective of this paper is not to formulate a concrete hypothesis for each of the institutional design criteria specified above. Nonetheless, it proposes two general hypotheses that reconcile the theoretical debate on deliberative forums with a bottom-up approach to legitimacy. First, on the basis of Lafont’s critique, one can hypothesise that non-participants will primarily care about the authorization mechanisms and reject any scenario where deliberative forums are vested with strong authorization, especially making binding decisions or recommendations without further processing by the democratic system (hypothesis 1). Second, one can assume a positive relation between (descriptive) representation and legitimacy (e.g., Thompson 2008). Warren and Gastil (2015: 568) argue that descriptive representation can bring public perspectives into deliberative processes and that the legitimacy of deliberative forums also depends on the fact that they are more descriptively representative than bodies determined by self-selection. However, a perception-based argument does not claim that non-participants automatically consider participants as their ‘representatives’; it is more likely that they perceive them for their ‘ordinariness’ (Gül 2019: 41) in opposition to elected politicians. Additionally, given the novelty of deliberative forums in democratic politics, they may be subject to a general perceived legitimacy deficit. Consequently, citizens might ask for ‘extra provisions’ when such forums are entitled to influence political decision-making. Concretely, hypothesis 2 states that legitimacy perceptions increase when deliberative forums are maximally representative and inclusive (which privileges random-sampling, large size, face-to-face and clear-cut majority recommendations).

Substantive Considerations

As argued earlier, legitimacy perceptions also hinge upon substantive considerations. First, empirical research on democratic preferences finds that legitimacy perceptions are conditional on issue type (Wojcieszak 2014; Goldberg et al. 2019). When citizens perceive an issue as salient, then they want to be involved, and hence favor direct participation and deliberation. This finding, however, relates to a direct comparison of participatory and deliberative forums with representative and delegative schemes. This article follows Lafont’s critique and argues that within deliberative forums, issue salience—which implies controversial and ‘high politics’ issues—may actually decrease legitimacy evaluations. Previous research has shown that deliberation works best when the issue is ‘least important’, i.e., when issue salience and controversy levels are low (Naurin 2010; Steiner et al. 2004). Translated to non-participants’ legitimacy perceptions, hypothesis 3 states that less salient and low politics issues processed by ‘novel’ deliberative forums are more ‘acceptable’ for non-participants than highly salient and high politics issues, and thus conduce to higher legitimacy perceptions. Second, research has shown that outcome favorability (the degree to which the policy outcome corresponds to one’s own preferences) matters for legitimacy perceptions as well. Esaiasson et al. (2012) and Marien and Kern (2017), for instance, have demonstrated that outcome favorability has the strongest effect on citizens’ decision acceptance. Hence, hypothesis 4 states that the more the results of a deliberative forum correspond to one’s own preference, the higher the legitimacy perceptions of non-participants.

The Role of Experience and Information

Perception-based approaches to legitimacy, however, presuppose that citizens are actually able to make proper legitimacy assessments. Deliberative forums, though, often lack visibility to the wider public and remain a ‘black box’ to non-participants (Rummens 2016). The majority of citizens are usually unaware of deliberative forums, making it quite difficult to assess relevant legitimacy perceptions. However, there are citizens who have already some experience of deliberative forums, either by directly participating themselves or by knowing how such forums work in real-world decision-making. Anecdotal evidence from deliberative experimentation in Germany suggest that experiences with citizen deliberation can conduce to both more positive and more negative evaluations of deliberative forums, this depending particularly on the perceived authenticity of the process, communication among different actor groups (like political and administrative officials and participants), and their expectations of the outcome of the process (see Vetter et al. 2015). Hypothesis 5 states that persons who already have experience with deliberative forums evaluate such procedures differently compared to people who have had no such experience so far. However, for most citizens, deliberative forums are abstract concepts, outside their experience of democratic practices. This is especially true when it comes to the various design features (such as random selection). Therefore, it is necessary both to familiarize non-participants with and give them information about the pros and cons of various design features (such as the advantages and downsides of random and self-selection, or the inclusion or exclusion of political actors). Becoming informed about the pros and cons of different design features of deliberative forums will not only help citizens to develop more informed opinions, but will also fulfill a critical aspect of Lafon’s critique, namely that citizens must be aware of deliberative forums and have thought through their (problematic) democratic implications. Put differently, as soon as non-participants understand that ‘blindly deferring’ to a deliberative forum recommendation means losing ‘authorship’ in a democracy—since one defers to people whose values, interests, and policy objectives we do not necessarily share—they will hardly see strong authorization of deliberative forums as legitimate. Hypothesis 6 states that full information, especially about the problematic authorization, should lead to a clear rejection of strongly authorized deliberative forums. In order to test this hypothesis, this study implemented an information component including a short description of deliberative forums, their design features, and various pro and con arguments on the latter (details of which are described below). Table 2 summarizes the hypotheses.

Hypotheses.

| 1. | Non-participants reject deliberative forums that are vested with strong authorization. |

| 2. | Legitimacy perceptions of non-participants increase when deliberative forums are maximally representative and inclusive. |

| 3. | Less salient and low politics issues processed by deliberative forums conduce to higher legitimacy perceptions of non-participants compared to highly salient and high politics issues. |

| 4. | The more the results of a deliberative forum correspond to one’s own preferences, the higher the legitimacy perceptions of non-participants. |

| 5. | Non-participants who are familiar with deliberative forums evaluate them differently compared to non-participants who are not familiar with them. |

| 6. | Full information leads to a clear rejection of strongly authorized deliberative forums. |

Experimental Design, Measurements and Statistical Analysis

The study is based on a conjoint experiment with an information treatment. While conjoint experiments have their roots in market research (e.g., Orme 2020), they have become a widely used standard in political science. The conjoint experiment was conducted at the University of Stuttgart in May 2019. A total of 231 persons participated; most of them were university students with a social science background. For the purpose of this analysis, all persons who were not enrolled at a university (25 persons) or did not provide information about their student status (39 persons) were excluded from the analysis. The final sample consisted of 167 participants, all exclusively university students (hereinafter ‘respondents’).6 In general, convenience samples of students lack external validity, especially when it comes to questions such as democratic legitimacy. Indeed, participants in the experiment were better educated, disproportionally female, younger, and had a higher political interest compared to the general population (for a comparison of the student sample with the whole sample and general population see Appendix A1). However, developmental psychologists have demonstrated that high school students (e.g., Helwig et al. 2007) from different cultural contexts, as well as university students (Esaiasson et al. 2012) are able to make judgments about democratic government quite similar to adults. Esaiasson et al. (2012) for instance found that high school students, university students and adult citizens rated the procedural fairness of direct majoritarian voting similarly.

Moreover, there is at least one argument speaking for using students with a social science background in this particular instance. As mentioned earlier, Lafont’s critique of deliberative forums requires that citizens have both some awareness and knowledge of deliberative forums. The sample consisted of university students a substantial part of whom (53%) were familiar with the concept of deliberative innovations.7 Moreover, one group of respondents were also provided with pro and con arguments regarding various authorization mechanisms and design features of deliberative forums while the other group received descriptions only (see below).8 Given that students generally possess higher abilities to process abstract concepts such as the design features of deliberative forums, we can conduct a proper counterfactual about how non-participants would judge the legitimacy of deliberative forums if they were fully informed about the various authorization mechanisms and design features of such forums and had thought them through. The participants of the sample were surprisingly heterogeneous in their attitudes with regard to democratic satisfaction and their general preferences for democratic decision-making (see Appendix A1). The results of this experiment should be interpreted with caution though. It may be the case that social science students are better equipped to assess deliberative innovations than ordinary citizens who do not yet know much about such procedures. For example, they may have learned theoretical arguments on what a ‘good deliberative citizen’ should endorse (or may even be familiar with Lafont’s arguments). Nonetheless, this makes it even more important to highlight the awareness gap which should be considered in follow-up studies.

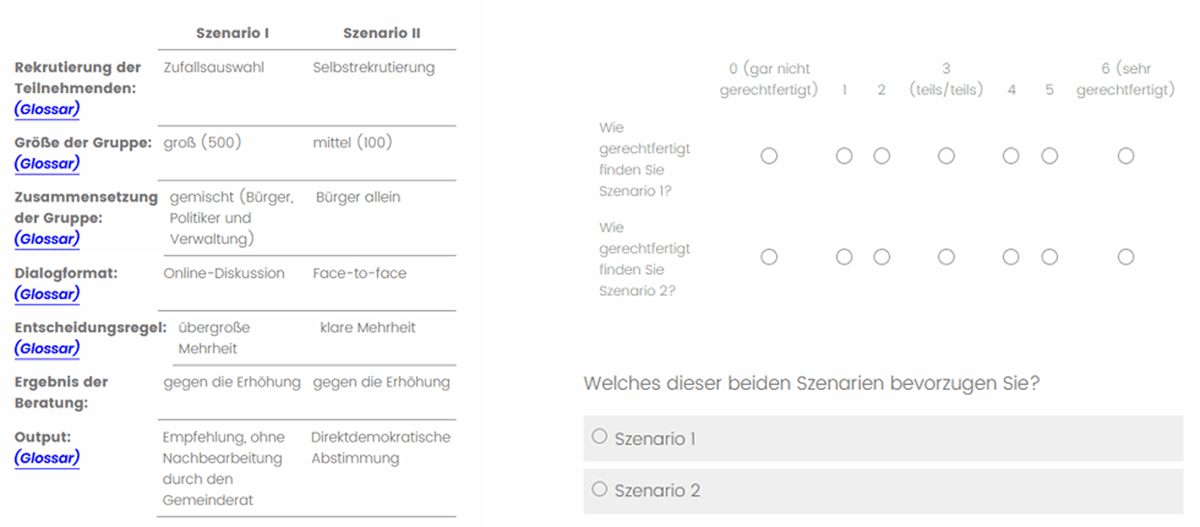

Conjoint experiments ask respondents to choose or rate hypothetical scenarios, which are each composed of multiple randomly assigned attributes. This allows estimating their relative importance (Hainmueller et al. 2014; Hainmueller et al. 2015; Horiuchi et al. 2018). The designs vary across seven attributes (see Table 1: recruitment, composition, size, dialogue format, majority, output, decision). Each attribute can take 2–4 randomly assigned characteristics. This study uses a paired conjoint design where respondents compare two scenarios on each attribute. Paired conjoints are particularly apt at replicating real world decisions (Hainmueller et al. 2014).

In order to assess perceived legitimacy, this article considers a ‘rating outcome’ (Hainmueller et al. 2014), comprising respondents’ numeric ratings of a certain scenario or scenarios. Although conjoint analysis often uses choice outcomes (i.e., whether a scenario is chosen over another scenario), rating outcomes can provide more information on respondents’ preferences (Hainmueller et al. 2014: 6). For the rating outcome, the experiment uses a standard indicator of procedural fairness theory (Skitka et al. 2003; Esaiasson et al. 2012): respondents were asked to evaluate the question ‘How justified is scenario X’ (Esaiasson et al. 2012). The scale ranges from ‘1’ (not at all justified) to ‘7’ (very justified). Each respondent assessed twelve comparisons between pairs of deliberative forums designs, each displayed on a new screen (for an example see Appendix A5). On average, scenarios have a rating score of 4.55, indicating that deliberative forums on average are perceived as mildly positive. Since studies often measure both choice and rating outcomes (Hainmueller et al. 2014: 7), all analyses were re-run for choice-based evaluations, but the results are identical (see Appendix A2).9

As indicated earlier, respondents were randomly assigned to two groups to examine information effects (Table 3):

An ‘information’-group was presented both with basic information and pro and con arguments about the different design attributes of deliberative forums.

A ‘glossary only’-group was presented with basic information about the different design attributes of deliberative forums but did not get pro and con arguments about the different design attributes.

Experimental Design.

| Information (n = 85) | Descriptions of different design attributes Information (pro & con) on different design attributes |

12 paired conjoints |

| Glossary Only (n = 82) | Descriptions of different design attributes | 12 paired conjoints |

In order to control for substantive considerations, issue salience and outcome favorability were included in the study. Respondents were presented with two political decision scenarios. The first was about the construction of an asylum home, the second about increasing waste disposal charges. Respondents were asked for their general preferences on these two topics (‘Would you agree to that construction/the raise?’). The construction of the asylum home issue was perceived as much more salient by the participants (an average of 8.17 on a 1–11 scale) than the increase of waste disposal charges (an average of 4.60 on a 1–11 scale); this difference is also statistically significant (p = 0.00). Next, actual decisions on both topics (for or against the construction of the asylum home/increase of waste disposal charges) were randomly assigned within the conjoint scenarios. Outcome favorability was then calculated by comparing respondents’ general preference for a given topic with the randomly assigned output of the scenario. On a scale running from 1 ‘reject proposal on [topic]’ to 11 ‘approve proposal [topic]’, respondents on average assigned the construction of an asylum home with a value of 8.5 and the increase of waste disposal with a value of 6.4. For each topic, values higher than 5 were coded as approval. Outcome favorability was then coded as a binary variable, taking ‘1’ if the decision of the deliberative forum (for or against the proposal on [topic]) matched the individual preference on the topic and ‘0’ if it did not. Finally, previous experience is coded as a dummy variable. Respondents who had either heard about deliberative forums or participated in them were assigned ‘1’; those who had never heard about them nor participated personally were assigned ‘0’. Unfortunately, it is not possible to differentiate between positive and negative experiences made with deliberative forums, since only very few respondents in the sample actually had active experience of them.

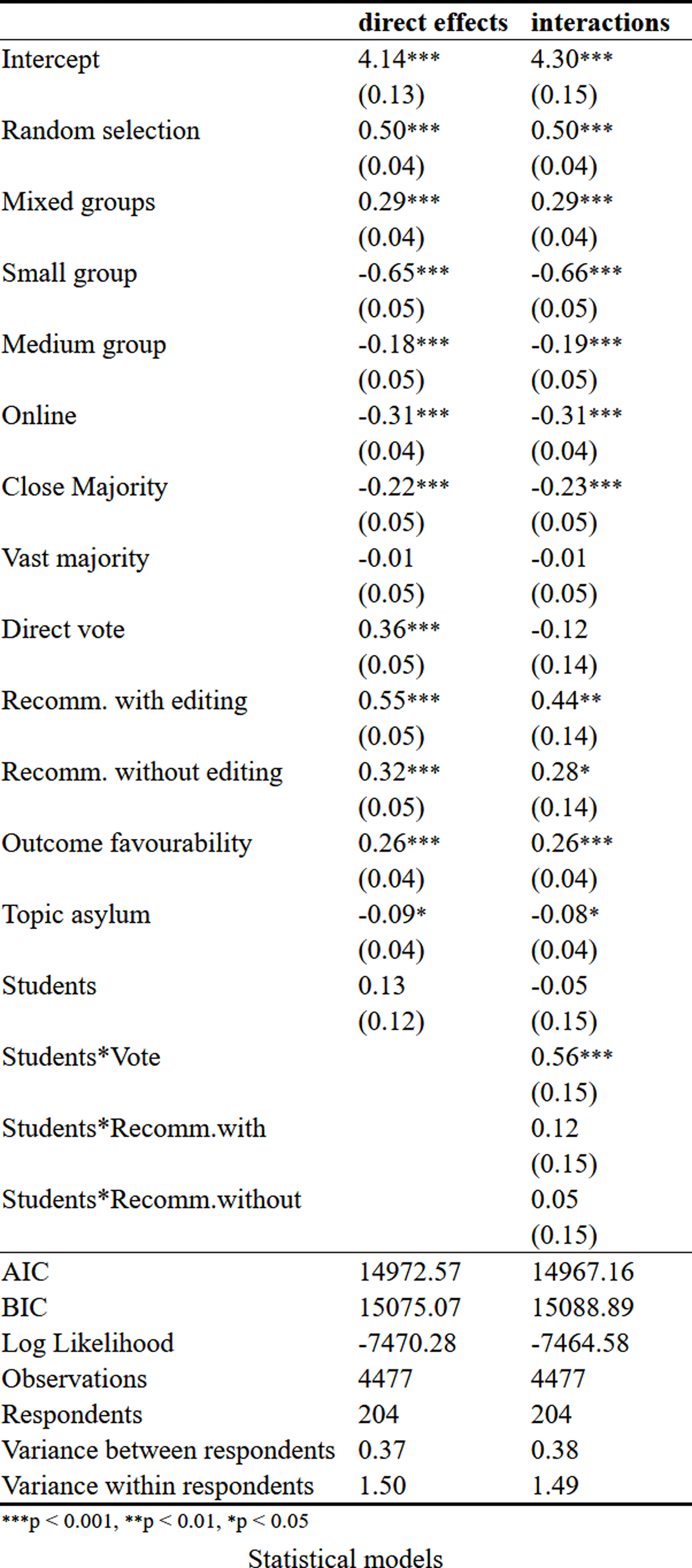

Regarding the statistical evaluation, one key strength of conjoint analyses is that they do not require that researchers observe all possible attribute combinations. Instead, it is possible to assess the average marginal component effects of each attribute (AMCE; Hainmueller et al. 2014). With regard to the rating outcome variable, AMCEs indicate the expected change in the rating of a deliberative forum when a given attribute value (e.g., random selection of participants) is compared to the chosen baseline (e.g., self-selection).10 Since the key units of analysis are evaluated scenarios, the dataset was transformed into long format. The dataset comprises 4008 observations (or 2004 pairings) for 167 respondents. Standard errors were clustered by respondent (Hainmueller et al. 2014). While AMCE analysis are the main vehicle of the statistical evaluation, Leeper et al. (2019) warn that using the AMCE analysis for descriptive purposes can be misleading since AMCE may be sensitive to the reference categories. Thus, marginal means (MMs)—the level of favorability toward deliberative forums that have a particular attribute level, ignoring all other attributes (Leeper et al. 2019: 4)—were additionally estimated (see Appendix A3). These estimations did not lead to substantially different results, but did help to better interpret effects, especially given that AMCE could be misinterpreted (Abramson et al. 2020). Finally, to double-check potential moderator effects of experience and information, multilevel regression techniques were used, complementary to the AMCE analyses. The latter enables statistical significance tests for the various moderator variables (see Appendix A4).

Results

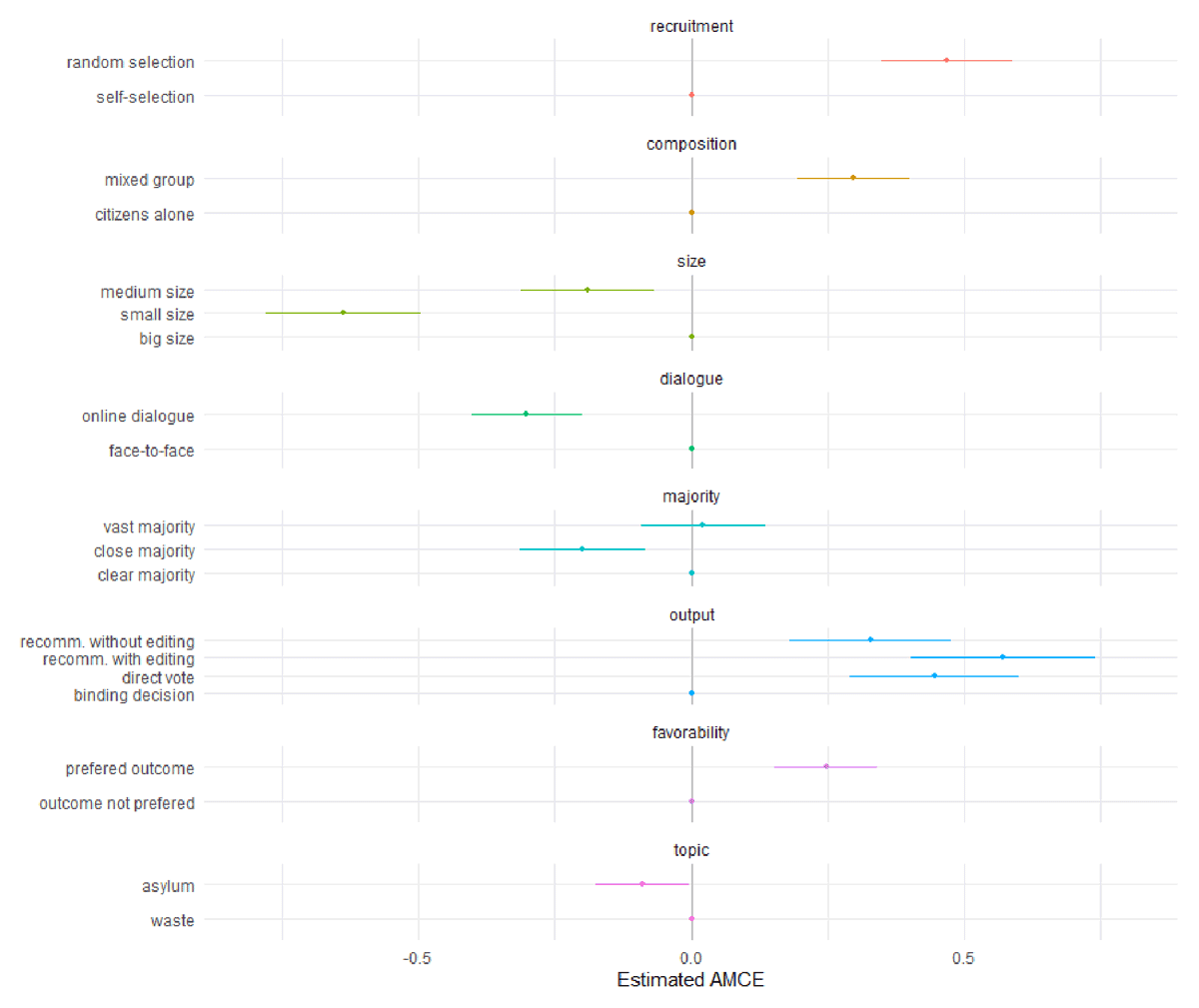

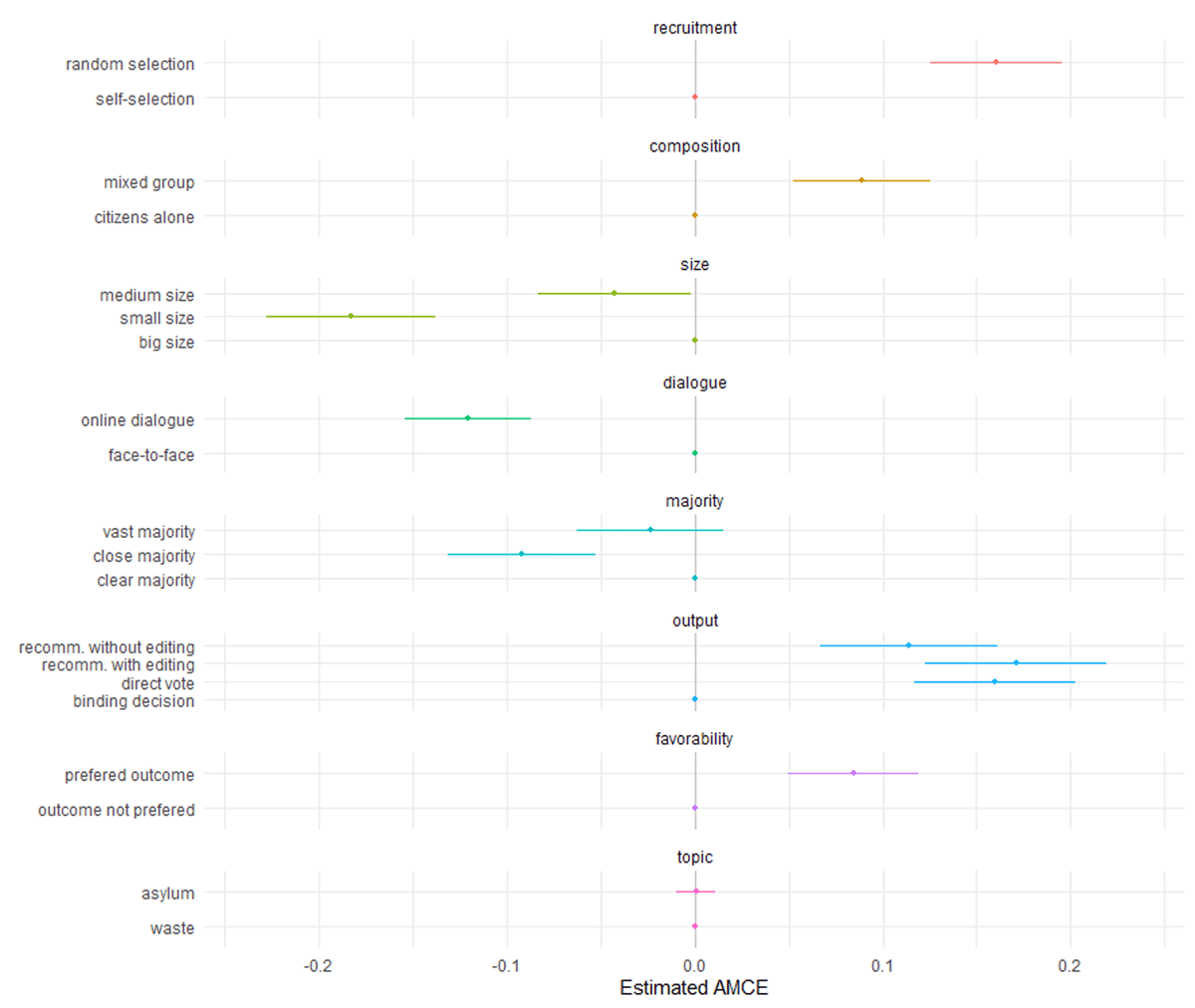

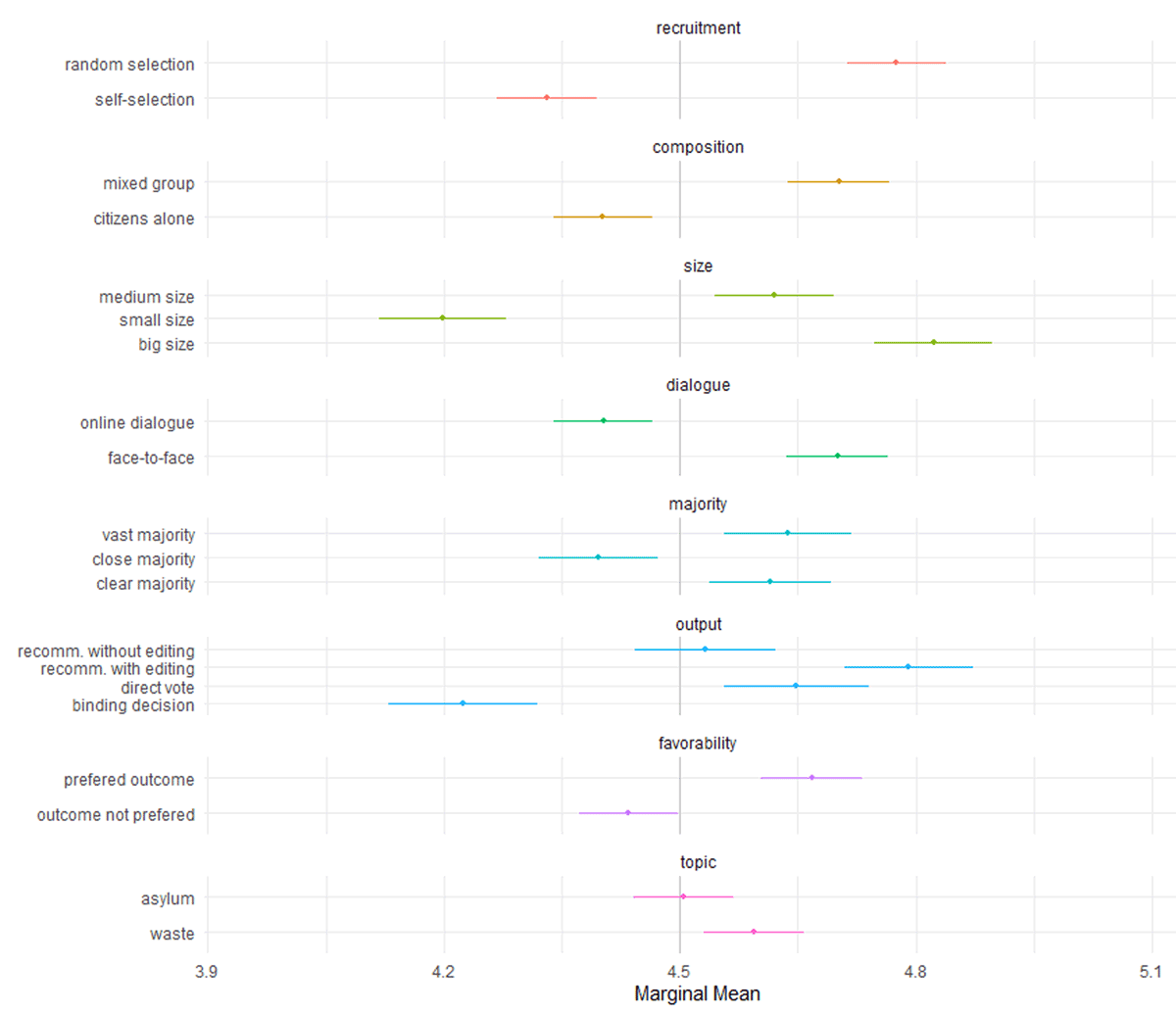

The presentation of the findings starts with the effects for authorization mechanisms followed by other design features of deliberative forums. For both, the paper explores which attributes of deliberative forums increase (or decrease) the legitimacy perceptions of respondents. As mentioned above, both AMCE (differences in effect sizes, causal interpretation; Figures 1 and 2; see Hainmueller et al. 2014) and MMs (descriptive differences, descriptive interpretation; Appendix A3; see Leeper et al. 2019) were used. The AMCE estimates are interpreted as the average change in the rating of a scenario when it included the design elements and their characteristics. For each attribute, the first characteristic (dots without confidence intervals) denotes the reference category. For instance, on a scale from 1 to 7, deliberative forums that use random selection for recruitment receive ratings that are 0.47 (half a scale point) higher than forums that use self-selection mechanisms. With regard to the choice outcome, using random selection instead of self-selection increases by 0.16 the probability that a deliberative forum will win support (see Appendix A2).

Effects of design characteristics on probability of choosing the scenario (y = rating outcome).

Note: The figure shows AMCE and 95% confidence intervals. Estimates are based on the regression estimators with clustered standard errors; the first attribute level for each attribute is the reference category. The AMCE estimates show the average change in the rating of a scenario when it included the characteristics compared to the baseline category for each attribute.

Regarding authorization mechanisms, the AMCE displays that respondents disliked binding decision-making in deliberative forums (reference category): respondents viewed all other authorization mechanisms in much more favorable terms (see attribute ‘output’, Figure 1). Additionally, as MMs (Appendix A3) illustrate, direct implementations are also the least popular output by far. The second least popular output was a recommendation put into effect without subsequent processing by the representative system (as in the Polish case of Gdansk). The most popular output was a recommendation with subsequent processing through representative bodies—that is, advice to elected officials who make the final decision (as we find it, for instance, in the Belgian G1000), followed by a recommendation of the deliberative forum put to a referendum (as happened with the results of the Irish citizen assemblies or CIR in Oregon). Note that the positive effect for deliberation followed by a referendum is most marked among students (Appendix A4). Remember, however, that students have probably already heard of positive cases like the Oregon model or Ireland. These results confirm Lafont’s critique (hypothesis 1) stipulating that deliberative forums should not have any direct decision-making powers, but only recommending force with further processing either by the democratic system or the citizens. They also corroborate Christensen’s (2020) findings that participatory processes should only have advisory roles.

Regarding other design features of deliberative forums, it turned out that respondents preferred random sampling with large groups, composed both of citizens and officials. Similar to the citizens’ assemblies in Ireland (Suiter et al. 2018), respondents preferred ‘co-governance’ schemes (combining citizens with political actors) to deliberative forums with citizens only. Moreover, respondents preferred face-to-face formats to online dialogues. With regard to majority recommendations within the deliberative forum, respondents wanted decisions to be taken via a clear-cut (and not just a close) majority vote; vast majority decisions, by contrast, did not boost respondents’ legitimacy considerations. Overall, these findings underline that non-participants want the authority of deliberative forums to be not only clearly circumscribed and minimal (hypothesis 1), but at the same time maximally representative and inclusive (hypothesis 2). As hypothesized, this seems to signal a more general legitimacy deficit of deliberative forums: compared to established representative institutions, they seem to require ‘extra’ provisions to generate higher levels of perceived legitimacy.

The importance of institutional design elements for respondents’ legitimacy perceptions underlines the significance of the procedural fairness framework. However, it turned out that issue salience and outcome favorability matter as well. As presumed by Lafont, the more salient issue (construction of an asylum home) received lower levels of perceived legitimacy than the less salient increase of waste disposal charges (hypothesis 3). Moreover, respondents also rated much more highly scenarios that entailed an outcome favoring their substantive policy preferences (hypothesis 4). Contrary to Esaiasson et al. (2012) and Marien and Kern (2017), however, outcome favorability was not the most important consideration of legitimacy perceptions; rather, authorization mechanisms and group size turned out to be the most important aspects for respondents’ evaluations. Interaction effects between issue salience and outcome favorability were also checked. Concretely, it was explored whether high issue salience and not getting a favored outcome contributed to even more negative legitimacy evaluations; however, the interactive effects were not significant.

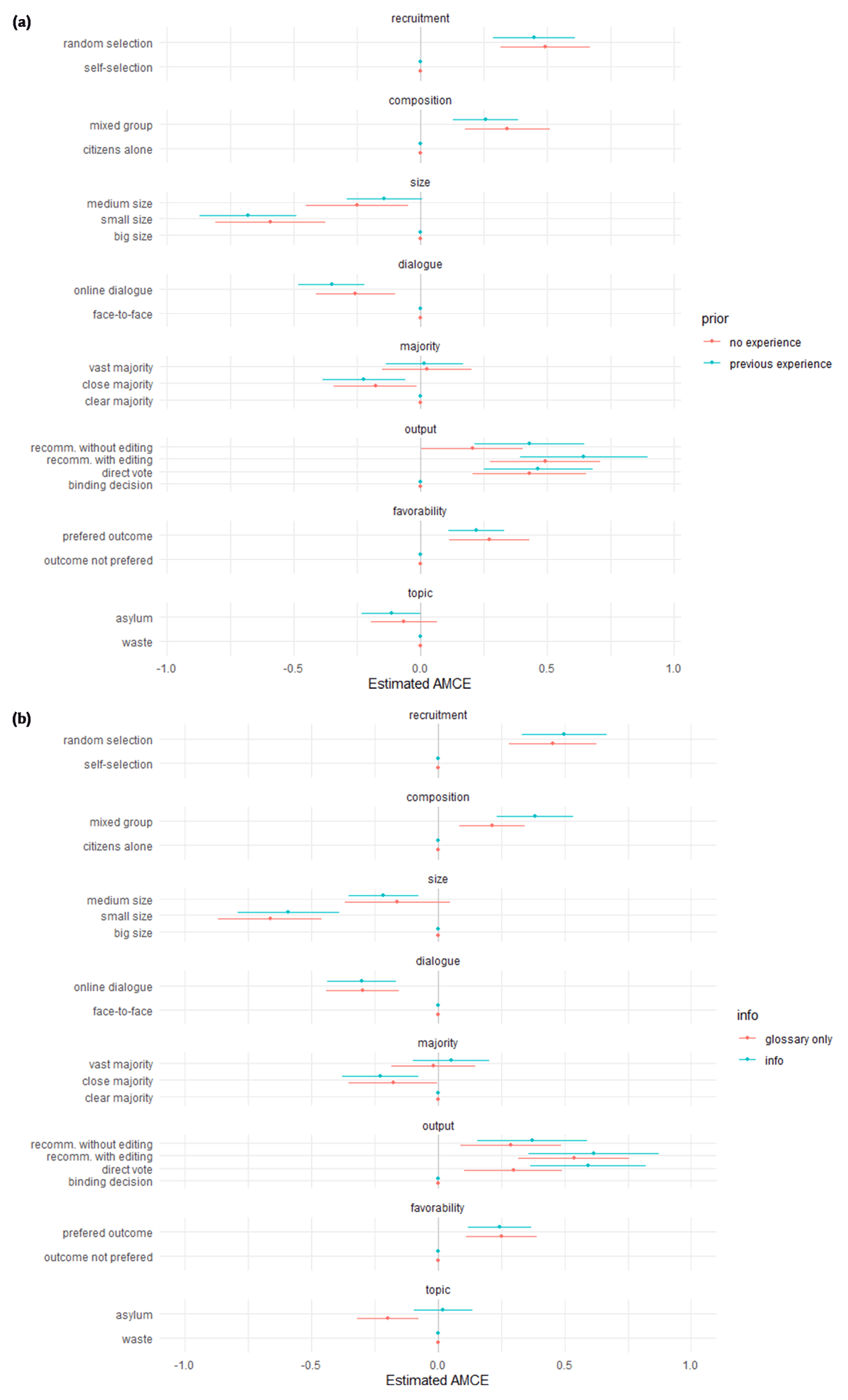

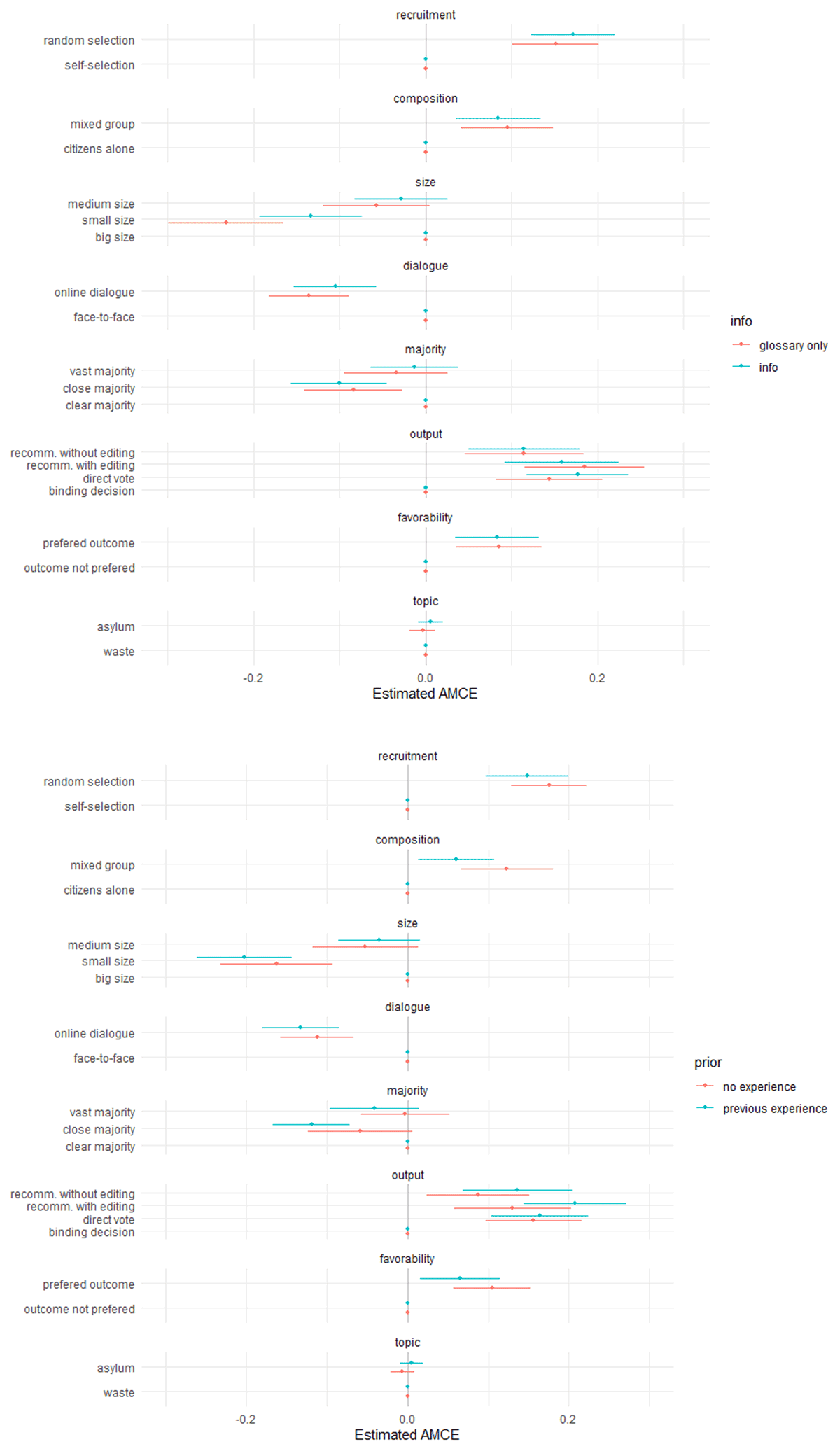

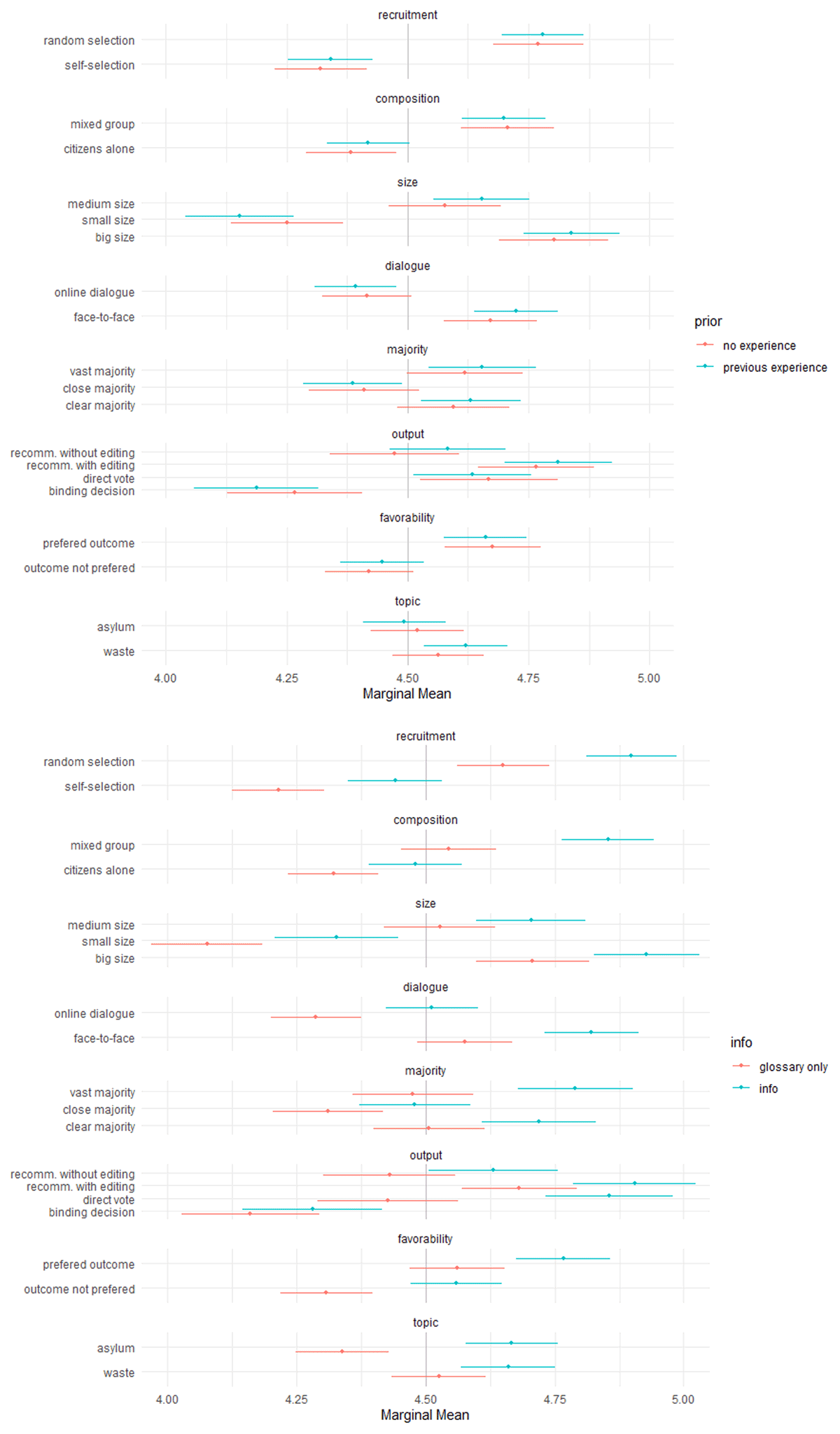

Finally, experience with deliberative forums and especially information on design elements matters for respondents’ legitimacy perceptions, in two ways. First, though general legitimacy perceptions do not significantly differ between those respondents who already have experiences with deliberative forums and those who have not, experience clearly conduces to more positive evaluations of all authorization mechanisms other than binding decisions (hypothesis 5). Intriguingly, this is most marked for deliberative forums making recommendations, compared to forums making binding decisions (Figure 2), as confirmed by the MM analysis (Appendix A3). Another intriguing finding is that the negative effect of issue salience (see above) is only significant for respondents who have already had some experience of deliberative forums.

Second, information on various design features leads to more positive evaluations for deliberative forums. As Figure 2 shows, respondents in the information group evaluated the various design elements of deliberative forums more positively than those who had just read descriptions in the glossary. This is even more marked when focusing on the MMs (Appendix A3). Intriguingly, the information group was even more supportive of authorization mechanisms other than binding decisions (hypothesis 6). This supports Lafont’s argument that full information should lead to an even stronger rejection of strong authorization mechanisms (especially binding decision-making). Additionally, the results indicate increased support for recommendations with subsequent referendums within the information group. With regard to other design features, more informed respondents more clearly reject small and medium sized groups. The difference between high and low saliency, however, is significant for the glossary group only. This indicates that arguments may help to level out topic dependencies. It is an open question, though, whether the information treatment was actually conducive to fully considered preferences: respondents also evaluated more positively those design features (such as majority considerations) that did not entail any pro and con argument. As such, information may have just contributed to an overall drive towards a more positive view of deliberative forums. Again, at least some students may have heard such arguments before, even those who were in the glossary-only group. Table 4 summarizes the empirical corroboration of the various hypotheses.

Hypotheses summary.

| 1. | Non-participants reject deliberative forums that are vested with strong authorization. | confirmed |

| 2. | Legitimacy perceptions of non-participants increase when deliberative forums are maximally representative and inclusive. | confirmed |

| 3. | Less salient and low politics issues processed by deliberative forums conduce to higher legitimacy perceptions of non-participants compared to highly salient and high politics issues. | confirmed |

| 4. | The more the results of a deliberative forum correspond to one’s own preferences, the higher the legitimacy perceptions of non-participants. | confirmed |

| 5. | Non-participants who are familiar with deliberative forums evaluate them differently compared to non-participants who are not familiar with them. | partly confirmed |

| 6. | Full information leads to a clear rejection of strongly authorized deliberative forums. | partly confirmed |

Conclusion: How to Move Ahead?

Citizen involvement in deliberative forums is frequently discussed with an eye to boosting the legitimacy of democratic decision-making. While some have argued for strong authorization (e.g., Buchstein 2019), Lafont (2015, 2017, 2020) has radically challenged this claim: when only a handful of citizens—even if randomly selected and ‘representative’ of the citizenry—determine political decisions for other citizens without being directly accountable to them, deliberative forums may decrease—rather than increase—democratic legitimacy. This is especially the case, so Lafont claims, when they deal with controversial and highly salient policy issues where citizens have strong opinions, and consensual solutions will not be forthcoming. To date, however, these questions have been primarily discussed at a theoretical level, without taking into account a bottom-up perspective that considers the views of non-participating citizens. Applying a conjoint experiment with students conducted at the University of Stuttgart in May 2019, this article finds that Lafont definitely has a strong point. The results suggest that the respondents of the experiment want the authority of deliberative forums to be clearly circumscribed and minimal, confirming Lafont’s critique. By the same token, they also want them to be maximally representative and inclusive. Specifically, respondents are not only strongly against deliberative forums making binding decisions or recommendations without further processing by the representative system: they also ask for an ‘extra provision’, meaning they prefer random selection, large size, and clear majority recommendations compared to self-selection, small size and recommendations with slim majorities. Moreover, legitimacy evaluations are also closely tied to issue salience and outcome favorability: legitimacy perceptions clearly increased when the issue was less salient and the (hypothetical) outcome favored respondents’ substantive policy preferences. This corroborates Lafont’s critique that substantive considerations complicate legitimacy evaluations of deliberative forums even further. Yet this study also adds nuance to Lafont’s critique: both previous experience with deliberative forums and information on the pros and cons of various design features conduce to higher legitimacy perceptions. From the perspective of deliberative forum advocates, this highlights the importance of making the functioning of deliberative forums more visible to a broader audience.

What can we learn from these first insights into citizens perceptions of deliberative forums? What are the practical implications for the questions of how and when to use them? With regard to the ‘how’ question, my results highlight one crucial point: citizens want deliberative forums to be implemented as a supplement to, not a substitute for, representative institutions. Although we do not know whether citizens really share the normative concerns raised by Lafont and others (or whether they are perhaps simply more cautious about such novel and unfamiliar institutions and therefore repudiate direct political impact), deliberative forums are best envisioned as intermediate, not direct, institutions from the perspective of citizens. With regard to ‘when’, this study would suggest a straightforward ‘occasionally’. Deliberative forums may not be appropriate for ‘solving’ all policy issues. My findings show that deliberative forums are viewed as less legitimate for more salient issues. Considering that some people may already have strong preferences regarding highly salient issues, deliberative forums will barely generate more legitimacy, and mediation processes involving stakeholders might do a better job in the context of such issues.

Further, my findings suggest that generating citizen awareness of deliberative forums is crucial for (more positive) legitimacy evaluations. Yet, in our competitive, partisan and mediatized democratic publics, deliberative forums frequently lack visibility (Rummens 2016; Bächtiger and Goldberg 2020) making their legitimate use a fairly tricky affair. While the conjoint experiment is pioneering in the sense that it puts advocates and critics of deliberative forums’ political uses to an empirical test involving a broad set of institutional design elements as well as connecting it with substantive considerations and information, it has several important limitations. A first and serious limitation is that the experiment only involved university students. This raises major external validity concerns, especially when it comes to a topic such as democratic legitimacy. We must therefore be very careful in making inferences or generalizing these findings. However, the article’s main contribution is explorative, and may work as a role model for further research. With regard to awareness, it has been argued that, somewhat paradoxically, the sample of social science students fulfilled one crucial criterion of Lafont’s critique, namely that non-participants must also have thought the issue through. Nonetheless, it is urgent to replicate the conjoint experiment with a representative sample of citizens and compare different subgroups within the sample. For example, there are indications, even in this student sample, that differential preferences for democratic models (representative vs. participatory) and satisfaction levels of democracy affected how respondents judged the legitimacy of deliberative forums (results available upon request). Citizens who are satisfied with the current ‘representative’ way of decision-making and those who perceive the system as being responsive see barely any merit in deliberative forums. On the other hand, citizens who generally want more participatory forms of democracy prefer deliberative forums that combine both deliberative and direct democratic elements. This also corroborates Goldberg et al. (2019), who found support for ‘integrated’ models of democratic governance among German citizens, combining deliberative and direct-democratic mechanisms. That said, future studies need to take citizens’ heterogeneity (Bächtiger & Goldberg 2020) into account. Deliberative forums may be an asset for some citizens, but not for all. Second, we also need cross-national studies on legitimacy perceptions. It is possible that citizens in different institutional and cultural contexts view the legitimacy of deliberative forums very differently. Third, future studies may also need to involve further institutional design elements of deliberative forums. This article has deployed a pragmatic approach, meaning that the selection of design elements comprised those that are relevant from a theoretical and practical perspective, with a particular eye on keeping the conjoint experiment manageable. But given the fact that the conjoint experiment worked well, one can also think of adding institutional design elements (e.g., whether a state or an NGO is in charge of a forum’s organization, or the duration of the deliberative forum) to future experiments. Finally, the information package involved ‘neutrally’ framed information on the pros and cons of the various design features and the authorization mechanisms. Yet deliberative forums have become increasingly politicized in current times; while there are strong advocates for such deliberative forums, there is also strong and persistent criticism of using them as policy-making forums.11 This would require an additional treatment, exposing respondents to stronger pro and con frames regarding the design and workings of such deliberative forums.

These limitations notwithstanding, this conjoint experiment has produced first insights on deliberative forums using a bottom-up perspective. While it confirms Lafont’s critique that deliberative forums may not be a panacea for boosting democratic legitimacy and quickly fixing the current crisis of democracy, it also adds nuance to her critique: legitimacy perceptions not only depend on deliberative design but also on citizens’ substantive considerations and on how much non-participants know about these deliberative forums.

Appendices

A1 Comparison and heterogeneity

Comparison sample and ESS 2016.

| Conjoint (students; n = 167) | Conjoint (full sample; n = 231) | ESS 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 24 years | 25.6 years | 51.4 years |

| Gender | |||

| male | 38.9% | 41.1% | 52.9% |

| female | 61.1% | 58,9% | 47,1% |

| Political interest | 84.3% interested (hereof 41,6% very interested) |

81.8% interested (hereof 42% very interested) |

68.1% interested (hereof 25% very interested) |

|

Political alignment (scale 1–11) |

4.44 | 4.42 | 5.40 |

| left | 59.9% | 59.8% | 29.6% |

| middle | 34.8% | 35.4% | 59.0% |

| right | 5.4% | 4.8% | 11.1% |

|

Trust politicians (scale 1–11) |

6.10 | 6.06 | 5.09 |

|

Satisfaction (scale 1–11) |

7.69 | 7.48 | 6.83 |

Heterogeneity within sample (students only).

| Preferences (scale 1–11) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Citizens should be involved more often in discussion formats before representatives make political decisions. | 7.61 |

1–4: 5–7: 8–11: |

2.4% 30.2% 69.4% |

| Political issues should more often be decided through a direct vote of the citizens. | 6.35 |

1–4: 5–7: 8–11: |

21,0% 46.7% 32.3% |

| Only elected representatives should make political decisions. | 6.11 |

1–4: 5–7: 8–11: |

22.7% 47.3% 30.0% |

| Independent experts should make political decisions. | 5.24 |

1–4: 5–7: 8–11: |

38.9% 39.5% 21.6% |

| I myself would like to participate in political discussions more often. | 7.98 |

1–4: 5–7: 8–11: |

12.6% 23.3% 64.1% |

| I myself would like to participate in direct-democratic votes more often. | 7.74 |

1–4: 5–7: 8–11: |

13.2% 30.5% 56.3% |

A2 Choice outcome (AMCE)

A3 Marginal means

A4 Multilevel models

Notes

- Deliberative minipublics are one of the most commonly used forms of democratic innovations. Typically, a ‘representative’ but mostly small sample of citizens deliberate on a particular policy issue in order to draft policy proposals (e.g., Setälä & Smith 2018). This article uses a broader term—deliberative forums—that allows the use of various design features (e.g., not only random selection but also self-selection). ⮭

- Communication with Cristina Lafont at the fourth Deliberative Democracy Summer School in Canberra, February 2020. ⮭

- Compared to other pioneering attempts (Christensen 2020; Jacobs 2019; Jacobs and Kaufmann 2021; Rojon et al. 2019), the approach in this paper is broader and not only engages with institutional design elements that are critical for the theoretical debate on deliberative forums but also takes both citizens substantive considerations into account while simultaneously dealing with the awareness gap. ⮭

- Christensen (2020) only distinguishes between binding decisions and advisory recommendations of deliberative forums. ⮭

- Perception-based determination of issue-salience. Participants in the experiment were asked how important they consider the issues of a) refugees and b) waste disposal. Average values show that the first topic has a much higher perceived salience than the latter. For detailed information see section on measurement. ⮭

- Analyses were re-run for the total sample of 231 participants; there were no systematic differences. Results available upon request. ⮭

- Of these, 48% have heard of deliberative forums and 5% have taken part themselves. ⮭

- The groups were nearly same-sized: A total of 85 respondents were in the information group (43 of them were already familiar with deliberative forums and 42 were not) and 82 respondents were in the glossary-only group (46 of them with previous experience and 36 without previous experience). ⮭

- For the choice outcome, respondents were asked ‘which of the two scenarios do you prefer?’ ⮭

- With regard to the choice-based variable (see Appendix A2). AMCEs indicate the average change in the probability that a deliberative forum will win support when it includes the listed attribute value (e.g., random selection) instead of the baseline attribute value (e.g., self-selection) (Hainmueller et al. 2014: 19). ⮭

- I thank Graham Smith for raising this important point. ⮭

Acknowledgements

I thank the anonymous reviewers for extremely useful comments on previous versions of this article. I also thank Cristina Lafont and the participants of the fourth Deliberative Democracy Summer School in Canberra in February 2020 for fruitful discussions.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

1 Abramson, S. F., Kocak, K., & Magazinnik, A. (2020, February 3). What do we learn about voter preferences from conjoint experiments? Retrieved from osf.io/qb4pf

2 Bächtiger, A., Dryzek, J. S., Mansbridge, J., & Warren, M. E. (2018). The Oxford handbook of deliberative democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198747369.001.0001

3 Bächtiger, A., & Goldberg, S. (2020). Towards a more robust, but limited and contingent defense of the political uses of deliberative minipublics. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 16(2), 33–42. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.390

4 Buchstein, H. (2019). Democracy and lottery: Revisited. Constellations, 26(3), 361–377. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8675.12429

5 Caluwaerts, D., & Reuchamps, M. (2018). The Legitimacy of citizen-led deliberative democracy: The G1000 in Belgium. Abingdon: Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781315270890

6 Chambers, S. (2009). Rhetoric and the public sphere: Has deliberative democracy abandoned mass democracy? Political Theory, 37(3), 323–350. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0090591709332336

7 Christensen, H. S. (2020). How citizens evaluate participatory processes: A conjoint analysis. European Political Science Review, 12(2), 239–253. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773920000107

8 Christensen, H. S., Himmelroos, S., & Grönlund, K. (2017). Does deliberation breed an appetite for discursive participation? Assessing the impact of first-hand experience. Political Studies, 65(1), 64–83. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0032321715617771

9 Dryzek, J. S., et al. (2019). The crisis of democracy and the science of deliberation. Science, 363(6432), 1144–1146. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw2694

10 Esaiasson, P., Gilljam, M., & Persson, M. (2012). Which decision-making arrangements generate the strongest legitimacy beliefs? Evidence from a randomised field experiment. European Journal of Political Research, 51(6), 785–808. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.02052.x

11 Esaiasson, P., Persson, M., Gilljam, M., & Lindholm, T. (2016). Reconsidering the role of procedures for decision acceptance. British Journal of Political Science, 49(1), 291–314. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123416000508

12 Farrell, D., et al. (2019). Deliberative mini-publics: Core design features. Centre for Deliberative Democracy and Global Governance working paper 2019/5. Canberra, Australia: Centre for Deliberative Democracy and Global Governance.

13 Fishkin, J. (2009). When the people speak: Deliberative democracy and public consultation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

14 Fishkin, J. (2018). Democracy when the people are thinking: Revitalizing our politics through public deliberation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198820291.001.0001

15 Fournier, P., van der Kolk, H., Carty, R. K., Blais, A., & Rose, J. (2011). When citizens decide: Lessons from citizens’ assemblies on electoral reform. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199567843.001.0001

16 Gastil, J., & Wright, E. O. (2019). Legislature by lot: Transformative designs for deliberative governance. London: Verso.

17 Goldberg, S., Wyss, D., & Bächtiger, A. (2019). Deliberating or thinking (twice) about democratic preferences: What German citizens want from democracy. Political Studies, 68(2), 311–331. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719843967

18 Grönlund, K., Setälä, M., & Herne, K. (2010). Deliberation and civic virtue: Lessons from a citizen deliberation experiment. European Political Science Review, 2(1), 95–117. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773909990245

19 Gül, V. (2019). Representation in mini-publics. Representation, 55(1), 31–45. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2018.1561501

20 Hainmueller, J., Hangartner, D., & Yamamoto, T. (2015). Validating vignette and conjoint survey experiments against real-world behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(8), 2395–2400. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1416587112

21 Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D., & Yamamoto, T. (2014). Causal inference in conjoint analysis: Understanding multi-dimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Political Analysis, 22(1), 1–30. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpt024

22 Helwig, C. C., Arnold, M. L., Tan, D., & Boyd, D. (2007). Mainland Chinese and Canadian adolescents’ judgments and reasoning about the fairness of democratic and other forms of government. Cognitive Development, 22(1), 96–109. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2006.07.002

23 Hennig, B. (2017). The end of politicians: Time for a real democracy. London: Unbound.

24 Horiuchi, Y., Smith, D., & Yamamoto, T. (2018). Measuring voters’ multidimensional policy preferences with conjoint analysis: Application to Japan’s 2014 election. Political Analysis, 26(2), 190–209. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2018.2

25 Jacobs, D. (2019). Deliberative mini-publics and perceived legitimacy: The effect of size and participant type. Paper presented at ECPR General Conference 2019, Wroclaw.

26 Jacobs, D., & Kaufmann, W. (2021). The right kind of participation? The effect of a deliberative mini-public on the perceived legitimacy of public decision-making. Public Management Review, 23(1), 91–111. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1668468

27 Lafont, C. (2015). Deliberation, participation, and democratic legitimacy: Should deliberative mini-publics shape public policy? The Journal of Political Philosophy, 23(1), 40–63. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/jopp.12031

28 Lafont, C. (2017). Can democracy be deliberative and participatory? The democratic case for political uses of mini-publics. Daedalus, 136(3), 85–105. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_00449

29 Lafont, C. (2019). Democracy without shortcuts. A participatory conception of deliberative democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198848189.001.0001

30 Leeper, T. J., Hobolt, S. B., & Tilley, J. (2019). Measuring subgroup preferences in conjoint experiments. Political Analysis, 28(2), 207–221. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2019.30

31 Mansbridge, J., et al. (2012). A systemic approach to deliberative democracy. In J. Parkinson and J. Mansbridge (Eds.), Deliberative systems: Deliberative democracy at the large scale (pp. 1–26). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139178914.002

32 Marien, S., & Kern, A. (2018). The winner takes it all: Revisiting the effect of direct democracy on citizens’ political support. Political Behavior, 40, 857–882. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-017-9427-3

33 Naurin, D. (2010). Most common when least important: Deliberation in the European Union Council of Ministers. British Journal of Political Science, 40(1), 31–50. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123409990251

34 Orme, B. K. (2020). Getting started with conjoint analysis: Strategies for product design and pricing research. Fourth Edition. Manhattan Beach, CA: Research Publishers LLC.

35 Parkinson, J. (2006). Deliberating in the real world: Problems of legitimacy in deliberative democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/019929111X.001.0001

36 Pateman, C. (2012). Participatory democracy revisited. Perspectives on Politics, 10(1), 7–19. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592711004877

37 Rojon, S., Rijken, A. J., & Klandermas, B. (2019). A survey experiment on citizens’ preferences for ‘vote-centric’ vs. ‘talk-centric’ democratic innovations with advisory vs. binding outcomes. Politics and Governance, 7(2), 213–226. DOI: http://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i2.1900

38 Rummens, S. (2016). Legitimacy without visibility? On the role of mini-publics in the democratic system. In M. Reuchamps & J. Suiter (Eds.), Constitutional deliberative democracy in Europe (pp. 129–146). Colchester: ECPR Press.

39 Setälä, M., & Smith, G. (2018). Mini-publics and deliberative democracy. In A. Bächtiger, J. S. Dryzek, J. Mansbridge, & M. E. Warren (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of deliberative democracy (pp. 300–314). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

40 Skitka, L. J., Winquist, J., & Hutchinson, S. (2003). Are outcome fairness and outcome favorability distinguishable psychological constructs? A meta-analytic review. Social Justice Research, 16, 309–341. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026336131206

41 Smith, G. (2009). Democratic innovations: Designing institutions for citizen participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511609848

42 Steiner, J., Bächtiger, A., Spörndli, M., & Steenbergen, M. R. (2004). Deliberative politics in action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511491153

43 Suiter, J., Farrell, D., & Harris, C. (2018). Ireland’s evolving constitution. In P. Blokker (Ed.), Constitutional acceleration within the European Union and beyond (pp. 142–154). Abingdon: Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781315453651-7

44 Thompson, D. F. (2008). Who should govern who governs? The role of citizens in reforming the electoral system. In M. E. Warren & H. Pears (Eds.) Designing deliberative democracy: The British Columbia Citizens’ Assembly (pp. 20–49). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511491177.003

45 Tyler, T. R. (1988). What is procedural justice? Criteria used by citizens to assess the fairness of legal procedures. Law and Society Review, 103–135. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/3053563

46 Tyler, T. R. (2006). What do they expect? New findings confirm the precepts of procedural fairness. California Court Review, 22–24.

47 Tyler, T. R. (2011). Why people cooperate: The role of social motivations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9781400836666

48 Tyler, T. R., & Blader, S. L. (2003). The group engagement model: Procedural justice, social identity, and cooperative behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 7(4), 349361. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0704_07

49 Van Reybrouck, D. (2016). Against elections: The case for democracy. London: Random House.

50 Vetter, A., Geyer, S., & Eith, U. (2015). Die wahrgenommenen Wirkungen von Bürgerbeteiligung. In Baden-Württemberg Stiftung (Ed.), Demokratie-Monitoring 2013/2014. Studien zu Demokratie und Partizipation (pp. 223–342). Wiesbaden: Springer VS. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-09420-1_6

51 Warren, M. E., & Gastil, J. (2015). Can deliberative minipublics address the cognitive challenges of democratic citizenship? The Journal of Politics, 77(2), 562–574. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1086/680078

52 Wojcieszak, M. (2014). Preferences for political decision-making processes and issue publics. Public Opinion Quarterly, 78(4), 917–939. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfu039