Introduction

Talking about politics with family, friends, and acquaintances is a crucial activity in democratic societies, as it enables citizens to come together as a community and understand matters of public concern (Barber 2003; Conover & Searing 2005; Mansbridge 1999; Neblo 2005). Along with sociability, there are intrinsic democratic benefits to everyday political talk, such as improving political knowledge; enabling citizens to rehearse, refine, and elaborate arguments and opinions; articulating personal and collective identities; and yielding meaning to daily facts (Huckfeldt & Mendez 2008; Maia 2012; Maia et al. 2020a; Maia et al. 2020b; Mansbridge 1999; Moy & Gastil 2006; Stromer-Galley & Wichowski 2011; Xenos & Moy 2007).

With the pervasive use of the internet and social media, everyday conversation is increasingly taking place online, ranging from inherently political environments—such as e-deliberation or e-participation platforms, political forums, and discussion boards—to social media and news websites (Graham 2012; Maia 2017; Maia & Rezende 2016; Shah 2016; Stromer-Galley & Wichowski 2011). Although few would question that the internet can foster political talk, scholars have been concerned with both the tone and the quality of these discussions as they consistently fail to live up to expected standards of public deliberation (Black et al. 2010; Coleman & Blumler 2009; Freelon 2013; Stroud et al. 2014).

Social networking sites, such as Facebook, promote inadvertent exposure to heterogeneous information, which can also lead to political disagreement (Barnidge 2018; Maia et al. 2020b). The use of social media platforms may enable citizens to learn about others’ views through their exposure to heterogeneous information, a core value of informal political discussion from the standpoint of deliberative democracy (Conover & Searing 2005; Gutmann & Thompson 1996; Maia 2018; Mutz 2006). Although many people might refrain from disagreeable conversations face-to-face, there is evidence that digital platforms can potentially provide a venue for engaging in such debates (Stromer-Galley, Bryant & Bimber 2015; Vaccari et al. 2016; Valenzuela & Bachmann 2015; Wojcieszak & Mutz 2009).

In this study, we examine political conversation triggered by exposure to political news on Facebook and news websites in Brazil and investigate the discursive and contextual characteristics associated with expressions of disagreement. In particular, we analyze the presence of disagreement in different discussion platforms (Facebook and news websites), focusing on types of news stories that elicit heterogeneous discussions, and the extent to which disagreement is associated with deliberative behavior, such as providing justification for one’s views. Considering the widespread concern around incivility online, we also investigate the relationship between disagreement and uncivil discourse, building an argument to distinguish between incivility and intolerant behaviors. This distinction is important because one should not assume that incivility is necessarily incompatible with democratic interactions, whereas intolerance poses an inherent threat to pluralism and democratic conversations (Rossini 2019).

Adopting the premise that argumentative interactions, even if not fully deliberative in everyday communication, may enhance a deliberative system (Parkinson & Mansbridge 2012), we argue that heterogeneous discussions online do not need to conform to high standards of political deliberation to be democratically relevant. Our results suggest that platforms hosting communication may influence the heterogeneity of discussion: comments are more likely to express disagreement on news websites than on Facebook. However, while expressions of disagreement posted on news websites address primarily news stories about formal politics, disagreements on Facebook focus on a wide range of story topics, suggesting that a more plural conversation occurs in online social networks. We find that disagreement is not a frequent feature of online political discussions, but, when it takes place, it tends to be associated with desirable discursive traits, such as reason-giving for one’s view and reciprocal replies. Taking into consideration the merits of heated debates for processing controversial issues, we argue that incivility underlying disagreement online may not be inherently problematic for democracy, insofar as divergence is expressed with a heated tone, but is not intolerant in substance.

Our study contributes to the understanding of online political talk as a process that is shaped and affected by distinct platforms, and suggests that the medium in which discussions take place influences the ways people express their political views. Moreover, this study suggests that more attention should be given to different types of disagreement, framed in terms of uncivil or intolerant expressions, to better understand the conditions and challenges for deliberative engagement in everyday discussions. Finally, by focusing on the Brazilian context, this study contributes to expand research on online political talk beyond English-speaking countries, which have been extensively scrutinized. Brazil has the fifth largest population and the fourth largest online population in the world—being the largest internet market in Latin America and one of the most active on social media1—making it a relevant country to help understand the practice of online political talk in the Global South.

Informal Political Talk Online

The internet, with its many channels, increases the amount and the availability of political content, and provides its users with opportunities to engage in informal discussions about topics of public concern—a practice that is central to democratic citizenship (Barber 2003; Dewey 1927; Habermas 1996). These conversations among citizens are at the heart of a strong democracy (Barber 2003), crucial to building communities and negotiating conflict. In spite of being a primarily social activity, informal political talk enables citizens to clarify their own views, learn about what others around them think and feel, and understand the issues that their communities face (Stromer-Galley & Wichowski 2011; Walsh, 2003).

Scholars have been scrutinizing the internet’s democratic potential and its ability to foster political talk for over two decades (Coleman & Blumler 2009; Coleman & Moss 2012; Maia 2014, 2018; Maia et al. 2020b; Stromer-Galley & Wichowski 2011). Given the characteristics of online communication, many scholars claim that it is unrealistic to expect that the deliberative criteria will be met in most political conversations online (Coleman & Moss 2012; Freelon 2013). It is relevant to note that the demanding criteria of deliberation are rarely met in most political discussions—even in formal and structured forums designed to foster political debate (Habermas 1996; Parkinson & Mansbridge 2012; Steiner 2012; Steiner et al. 2017). Thus, the lack of deliberative qualities is not enough to dismiss online political talk or prevent it from having positive political outcomes—such as increasing political knowledge, fostering shared values, and providing meaning on matters of public concern.

In this article, we turn our attention to disagreement as a key aspect of democratically relevant political talk. Exposure to, and engagement with, crosscutting perspectives is among one of the main characteristics of democratic deliberation: discussions should be inclusive of diverse views, and the goal of deliberation is to enable mutual recognition of diverse claims (Esterling, Fung & Lee 2015). Esterling et al. have argued that ‘disagreement is at once a condition and a challenge for deliberation’ (2015: 529), because while some people might welcome heterogeneous discussions and are open to learn from them, others may refrain from these debates or become more entrenched in their own positions. A number of studies have inquired into how individuals respond to disagreement. Mutz (2002, 2006), for instance, finds that exposure to disagreement and ‘crosscutting views,’ while promoting tolerance and understanding of opposing views, may also lead to avoidance of controversy and to political apathy. The key argument is that demand for providing explanation to one’s view when disagreeing with others would reduce the individuals’ willingness to express their preferences and leave them ambivalent about complex issues (Mutz 2002, 2006).

Some scholars contend that exposure to controversial views may increase individuals’ political knowledge and willingness to participate in public discussions (Eveland 2004; Moy & Gastil 2006; Rojas 2008). Other studies, taking into account the individual network-size level, did not identify a significant relationship between exposure to political disagreement and avoidance of controversies (Huckfeldt, Johnson & Sprague 2004; Lee, Kwak & Campbell 2015; Nir 2005). Esterling et al. (2015) further suggest that the discussants’ perception of levels of disagreement—i.e., moderate disagreement and intractable disagreement—yields different effects for democratic discussions. In spite of the nuances in how disagreement is measured or perceived, research on informal political conversation emphasizing its intrinsic and extrinsic benefits provides evidence that relatively unstructured, informal heterogeneous discussions that happen in people’s daily lives have democratic value even when they are not characterized by deliberative norms and processes (Eveland 2004; Eveland & Hively 2009; Maia et al. 2020a; Maia et al. 2020b; Scheufele et al. 2004; Valenzuela, Kim & Gil de Zúñiga 2012).

Contrary to early expectations that the internet would expose users to echo-chambers, predicting negative consequences of selective exposure in high-choice and algorithmically curated online environments (Pariser 2011; Sunstein 2009), there is substantial empirical support suggesting that the internet, in general, and social media, in particular, exposes users to more diverse information, on purpose or inadvertently (Anspach 2017; Brundidge 2010; Vaccari et al. 2016). Several studies have revealed that social media—platforms in which users are responsible for producing, sharing, or curating content—weakens social boundaries and facilitates inadvertent exposure to political differences (Brundidge 2010; Garrett, Carnahan & Lynch 2013; Vaccari et al. 2016). The weaker the social ties are in online networks, the more numerous and diverse the types and sources of information that users are exposed to (Gil de Zúñiga, Jung & Valenzuela 2012). Even in platforms designed to prioritize content that aligns with users’ preferences through algorithmic filtering and ranking (e.g., Facebook), challenging views still surface because most people’s personal connections are made for reasons other than sharing political views (Bakshy, Messing & Adamic 2015). Relationships play a crucial role in influencing access to information on Facebook, as users are more likely to select political news that is shared by their peers (Anspach 2017). Research has also found that social media users tend to perceive more disagreement (with the content they are exposed to, such as posts and discussions) than nonsocial media users, and that they also tend to perceive it more on social media than in anonymous online environments or face-to-face (Barnidge 2017).

In this context, it is important to investigate the role of platform affordances in structuring interpersonal communication online (Fox & McEwan 2017). Our study focuses on two popular venues for informal political talk: Facebook and the comments section of news websites. These environments differ in many ways, such as levels of identification, presence and visibility of social ties, and moderation—all of which can influence the extent to which participants engage with political disagreement (Barnidge 2017; Halpern & Gibbs 2013; Maia et al. 2020b). Considering these different affordances, it is plausible to expect that the social constraints of a social media platform—having a personal and identifiable profile, or maintaining visible social ties (Ellison & Boyd 2013)—might affect the extent to which Facebook users engage in disagreeable political talk when commenting on news—as the presence of others whom they know personally may act as a social constraint, as is the case in face-to-face discussions (Mutz 2006). If we consider that anonymous online environments are often associated with a ‘disinhibition effect’ (Suler 2004), that is, users feel less connected to their ‘real’ identities and are therefore less concerned about social sanctions, it follows that news websites should have less constraints than social media for users to engage in heated discussions, as those who comment on news websites routinely use nicknames or aliases that protect their identities, and their personal connections are neither revealed nor visible. Thus, we hypothesize that we will find different levels of disagreement in the two platforms selected for this study, with crosscutting perspectives being expressed more frequently on news websites:

H1: Comments on news websites will have more disagreement than comments on news shared on Facebook.

Research examining the benefits of crosscutting exposure and disagreement in political talk is often based on self-reported measures of types and frequency of conversation, without measuring its quality, and conflicting results in the literature can be partially explained by methodological differences in how disagreement is measured and conceptualized. Studies have shown significant differences between perceived disagreement and objective disagreement in actual discussion practices (Wojcieszak & Price 2012) and variations in the nature of disagreement in online settings and face-to-face settings (Stromer-Galley et al. 2015). Moreover, the type of issue being discussed is an important factor that influences disagreement (Hong & Rojas 2016; Wojcieszak, Baek & Carpini 2010; Wojcieszak & Price 2010), and research on online political talk tends to focus on particular topics and issues—often contentious ones (Hmielowski, Hutchens & Cicchirillo 2014; Papacharissi 2004; Rowe 2015; Zhang & Chang 2014). In addition to the context of interaction, the type of issue being discussed is an important factor that influences disagreement (Hong & Rojas 2016; Wojcieszak et al. 2010; Wojcieszak & Price 2010). Taking into consideration that people who discuss politics on news websites might be different (e.g., in terms of interests, demographics, or motivations) from those who engage with political talk on Facebook, it is relevant to investigate whether there are differences between the nature of news stories that will drive more disagreement in the two platforms. Because these relationships have not been sufficiently explored, we ask:

RQ1: Are there differences in which news topics are more likely to generate disagreeable comments on Facebook and news websites?

Disagreement is seen as a desirable discussion trait because it enables people to better understand each other’s views, as well as to reflect on their own (Esterling et al. 2015; Gutmann & Thompson 1996; Habermas 1996; Mutz 2006; Parkinson & Mansbridge 2012; Steiner 2012). Several studies about online discussion, being framed by Habermas’ concept of public deliberation, have attempted to measure the extent to which online discussions conform to a set of normative ideals—such as rational and respectful exchange of arguments that are justified and driven by the common good instead of personal gains (Mansbridge 1999). It is, however, well known that less structured discussions take place in many internet channels that are not designed to promote deliberation (Chadwick 2011; Eveland, Morey & Hutchens 2011). Given the characteristics of online discussions, many scholars claim that it is unrealistic to expect that the deliberative criteria will be met in most political discussions online (Coleman & Moss 2012; Freelon 2013). Furthermore, it is relevant to note that the demanding criteria of deliberation are rarely met in most political discussions—even in formal and structured forums for political debate (Habermas 1996; Parkinson & Mansbridge 2012; Steiner 2012). That said, we understand that the lack of deliberative qualities does not prevent online political talk from having positive political outcomes—such as increasing political knowledge, fostering shared values, and providing meaning on matters of public concern (Huckfeldt & Mendez 2008; Maia 2012; Mansbridge 1999; Moy & Gastil 2006; Stromer-Galley & Wichowski 2011; Xenos & Moy 2007).

In this context, we argue that the aforementioned benefits are grounded on the premise that people are able to articulate their opinions in the context of disagreement so that participants in a discussion can proactively know about others’ positions, understand their perspectives, and engage with their arguments. To assess the democratic value of online disagreement, we should investigate the extent to which expressions of divergence are associated with reason giving to back up one’s opinion. Then we ask:

RQ2: Is disagreement online positively associated with justified opinion expression?

Uncivil Disagreement?

Although scholars have adopted different standards to analyze the quality of online conversations, most agree that the presence of incivility can undermine the potential benefits of political discussion (Hmielowski et al. 2014; O’Sullivan & Flanagin 2003). Online incivility is facilitated by many of the affordances that have been historically associated with the internet’s potential to foster democratically relevant political talk, such as the ability to talk with others beyond geographical barriers and engage with homogeneous and heterogeneous groups, and the possibility to express oneself without fear of discrimination (Papacharissi 2004).

In particular, research has consistently associated anonymity—the ability to use aliases or nicknames—with incivility, flaming, and trolling (Hmielowski et al. 2014; Huckfeldt & Mendez 2008; Turner 2010). One explanation is that users become disconnected from their real identities and may become more inclined to adopt antinormative behaviors without the fear of sanctions (Suler 2004). With the rise of social media, political talk online, however, increasingly takes place in environments that are not anonymous. Facebook, for instance, has a policy of ‘real names’ and is designed around personal profiles with pictures and publicly available lists of friends that are mostly comprised real relationships—even though many connections listed are acquaintances or colleagues (Ellison & Boyd 2013). Studies comparing comments on news websites with those made on Facebook pages have found similar levels of uncivil behaviors—suggesting that anonymity is not the only factor influencing incivility2 (Rossini 2019; Rowe 2015).

A problem with online incivility research is the lack of conceptual clarity, and studies often conflate inherently harmful behaviors (such as expressions of racism, sexism, or hate speech) with expressions that, while disrespectful, vulgar, harsh, or intense, are not necessarily offensive (Anderson et al. 2014; Coe, Kenski & Rains 2014; Hmielowski et al. 2014; Rowe 2015; Sobieraj & Berry 2011). In spite of the lack of nuance, the presence of incivility has led scholars to deem online political talk as being of low quality (Santana 2014). As warned by Papacharissi (2004), dismissing online discussions due to the presence of incivility means dismissing the value of heated conversations. Calls for civility can also be criticized as attempts to limit the types of discourse that are accepted in the public sphere, which can silence particular forms of expression (Benson 2011).

Aligned with the argument that incivility might be compatible, or even normalized, by those who discuss politics online (Hmielowski et al 2014; Sydnor 2018), this study adopts a conceptual distinction between incivility and intolerance. In this framework, incivility is operationalized as a set of features that determine the ‘tone’ of political discourse, such as the use of vulgar or profane words, personal attacks, attacks toward arguments, and other rhetorical features that may make discourse potentially offensive (Coe et al. 2014; Sydnor 2018). Intolerance, on the contrary, comprises behaviors that denote profound disrespect toward others based primarily on individual characteristics, preferences, or beliefs, as well as expressions of hatred, and violent threats (Gibson 1992; Rossini 2019). These behaviors are independent: comments can be uncivil but tolerant, or civil but intolerant. While the former refers to tone of discourse (e.g., shouting, interrupting, using profanities, lack of interpersonal respect), the latter refers to substance: rhetoric that is inherently abusive, exclusionary, or in violation of moral respect.

Disagreement practices alongside uncivil and intolerant expressions can vary and have distinct consequences for democratic political talk. In the context of citizens’ everyday discussions, both uncivil expressions and intolerant expressions have the potential to block discursive engagement, lead to hostile reactions, or a painful silence. Both forms of disagreement can, at times, foster critical reflections and lead to a strong pushback. When a broader perspective of democratic political talk is considered; however, intolerance is toxic because it denies pluralism and the equal status of citizens, providing a fertile ground for advancing similarly minded disrespectful and cruel forms of domination such as discrimination, stigmatization, exclusion, exploitation, etc. (Maia 2014, 2017). Incivility, on the contrary, may have fewer problematic effects to the extent that some expressions of incivility—for instance, toward political arguments—are perceived as acceptable by citizens (Hmielowski et al 2014; Muddiman 2017; Sydnor 2019).

Following the argument that incivility may be used as a rhetorical asset that can help make positions stand out amidst noisy and crowded debates, the diversity of viewpoints in online political discussions might encourage participants to rely on uncivil discourse as a means of expressing themselves (Herbst 2010; Papacharissi 2004; Rossini 2019). For instance, comparing online and offline discussions, Stromer-Galley et al. (2015) found that people are significantly more likely to be uncivil online in the context of political disagreement. The same is not necessarily true for political intolerance, as these behaviors tend to be more salient in more homogeneous environments (Crawford & Pilanski 2014; Gibson 1992; Wojcieszak 2010, 2011). Although prior research has given us some indication of the direction of the relationships of these behaviors with the heterogeneity of a discussion space, the conceptual distinction between incivility and intolerance in online political talk warrants a set of exploratory questions to investigate the extent to which these behaviors are associated with disagreement.

RQ3: Are expressions of disagreement associated with incivility?

RQ4: Are expressions of disagreement associated with intolerance?

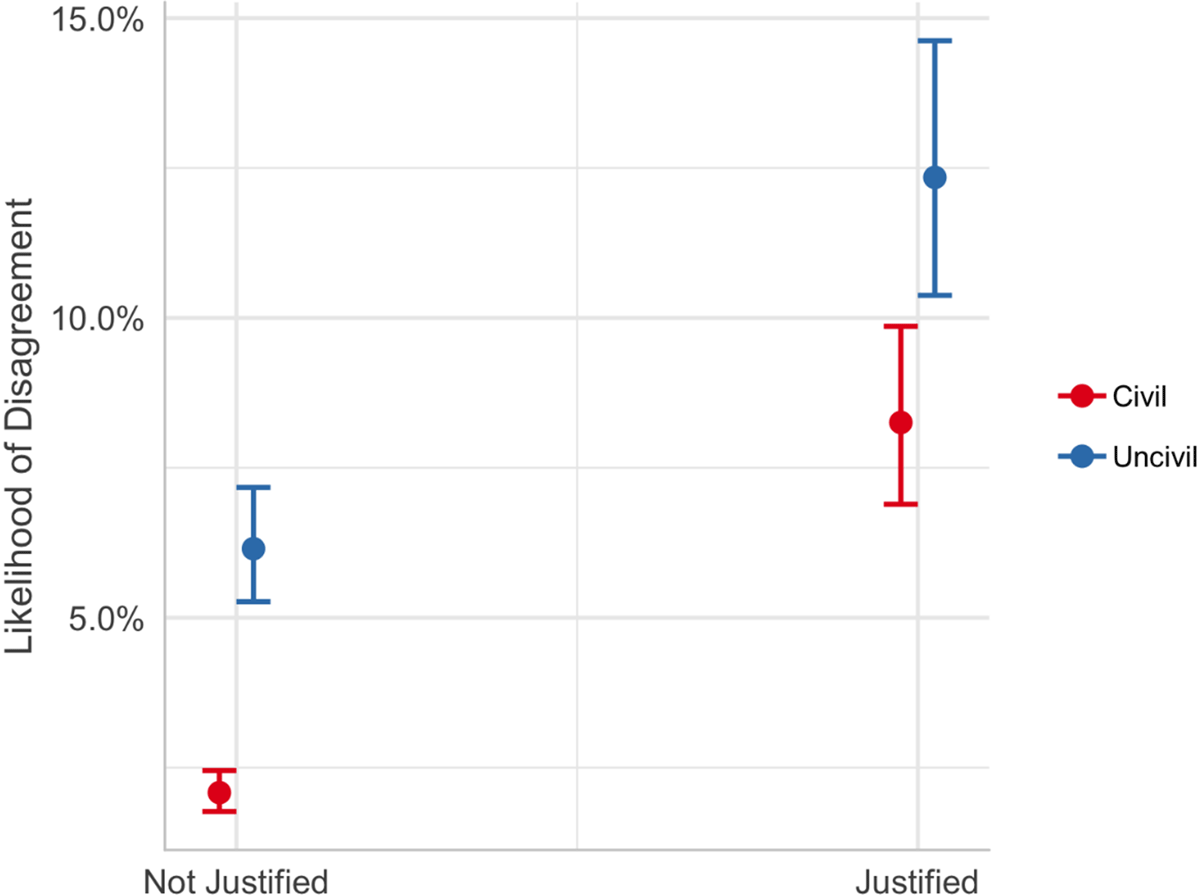

If one of the benefits of exposure to disagreement is learning about others’ views, it should follow that opinions need to be explained so that others can understand them. Although incivility may affect participants’ openness to opposing views and may have detrimental effects on people’s willingness to participate in a discussion (Gervais 2014; Sydnor 2019), it also improves recall and attention to arguments (Mutz 2016; Maia et al. 2020b). Thus, it should follow that expressions of disagreement that are uncivil should still enable people who are exposed to them to learn about others’ perspectives when these are justified, regardless of the tone used to express them. To explore this relationship, we examine interaction effects between justified opinion expression and incivility in predicting disagreement in online comments.

RQ5: What is the relationship between incivility and justified opinion expression in predicting comments with disagreement?

Methods

Data collection

We analyzed comments from news stories shared by Portal UOL’s Facebook page—the most popular online news outlet in Brazil, with more than 6.7 million Facebook followers in 2016. Portal UOL was selected as the source for news stories and comments due to the fact that it is the largest online content portal in Brazil, hosting several media outlets ranging from national and local newspapers, entertainment websites, and opinion blogs, along with proprietary news content. On Facebook, UOL shares a mix of stories from these news partners as well as its own content, allowing for a varied range of sources in the sample. We used constructed week sampling to account for the variability of the media cycle, and selected two constructed weeks to represent a 6-month period of online news—from February to July 2015 (Connolly-Ahern, Ahern & Bortree 2009; Hester & Dougall 2007). Each week was constructed by randomly selected weekdays within the timeframe of the analysis.

We compared comments on the same stories to ensure that differences in the comments were not derived from the discussion of different news stories—given the nature of the data, we are unable to make inferences about the public in these two platforms. We build a comparative dataset following the links to political stories shared on Facebook posts to scrape the comments from their original source—most frequently UOL and Folha de São Paulo, Brazil’s main newspaper, and blogs specializing in politics.3 Portal UOL shared 1,669 news stories on Facebook during the two constructed weeks. These stories were initially classified as political or nonpolitical, using a broad notion of political news, which includes stories about formal political affairs, as well as policy-related public issues (e.g., education, security), organized civil society, international affairs, minorities, and celebrities engaged in social causes or that were the subject of discriminatory scandals. After removing duplicated news stories (i.e., those posted on Facebook more than once), stories with zero or one comment, and stories from sources that used a Facebook plugin for comments, the final sample of political news had 156 stories from eight news sources and a universe of 55,053 comments, with around 70% of this total (n = 38,594) being on Facebook. The three main sources of comments, Portal UOL (55.9%), UOL Blogs (19.2%), and Folha de S. Paulo (16.9%) had similar commenting affordances, with participants registered under pseudonyms and systematic human moderation to filter out violations to terms of service. Manual content analysis was conducted on a random stratified sample4 of these comments (N = 12,337) to account for differences in the proportion of comments in each platform, and in the number of comments on each story. Our sample includes discussion threads instead of isolated messages: consecutive messages were selected using a random number in the universe of comments of a story as a starting point to collect comments in each story.

Content analysis

We used systematic content analysis to classify public comments (Neuendorf 2002), using a coding scheme broadly inspired by prior research (Coe et al. 2014; Stromer-Galley 2007), with original categories created for this study. The analysis was conducted by two independent coders, and all categories were considered reliable (Krippendorff’s alpha greater than 0.68).5

The codebook operates with two distinct units of analysis: news stories and messages. The news stories were coded by their topics: politics (government, congress, politicians); civil society (NGOs, activism, social movements); celebrities; minorities; public policy; and international affairs. Due to a low number of comments, stories featuring celebrities were recoded as the broader political issue they addressed—minorities—as the stories featured celebrities targeted by racism or homophobia.

Messages were coded in the following main categories6: target of interaction; disagreement; opinion expression; incivility; and intolerance. Target of interaction identified whether the message was a direct reply to a previous comment (using a reply feature or mentioning someone else’s name). Incivility was classified using the following subcategories: mockery, disdain, dismissive or pejorative language, profanity, and personal attacks7 (e.g., referring to personality, ideas, or arguments). Intolerant messages were coded in the following subcategories: xenophobia, racism, hate speech, violence, homophobia, religious intolerance, and attacks toward gender, sexual preferences, or economic status. Intolerant and uncivil messages were also coded by focus, which can be other users, political actors, people or groups featured on the news, the media, political minorities, or unfocused. This variable identifies whether uncivil and intolerant discourse is targeted at other discussants, signaling lack of interpersonal respect, or at other actors who are not a part of the conversation. Messages were coded as disagreement when they (1) diverged with the general tone of the discussion (considering the previous message in a thread as the baseline),8 which indicates heterogeneity in the thread or (2) explicitly diverged from another commenter in the form of either name tagging or reply. The category of opinion expression also had two subcategories: (a) unjustified opinion expression, coded as any remark that revealed a commenter’s take on a topic without any elaboration and (b) justified opinion expression, coded when there was any explanation or elaboration to substantiate an opinion.

Results

We identified disagreement in only 11.6% of the sample (N = 1,425), with significant differences between Facebook and news websites at the bivariate level. Proportionally, disagreement occurred more frequently in news websites (15.1%) than on Facebook comments (10%), X2 (1) = 68.160, p < 0.0001 (Table 1). The table presents the frequency of disagreement per story topic, showing significant differences in the types of stories that trigger heterogeneous debates. The bivariate analysis suggests that platforms influence the extent to which participants are exposed to disagreement (Table 1) in the direction hypothesized (H1).

Frequency of disagreement per platform and topic.

| Disagreement | No disagreement | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 847 (10%) | 7,664 (90%) | X2 (1) = 68.160 | |

| News sources | 578 (15.1%) | 3,248 (84.9%) | p < 0.0001 |

| News topic | |||

| Political news | 792 (10.7%) | 6,582 (89.3%) | X2 (4) = 148.112 |

| Minorities | 469 (17.2%) | 2,254 (82.8%) | p < 0.0001 |

| Policy | 110 (6.8%) | 1,503 (93.2%) | |

| Civic society | 48 (13%) | 321 (87%) | |

| International | 6 (2.3%) | 252 (97.7%) | |

| Total | 1,425 (11.6%) | 10,912 (88.4%) | |

Only row proportions are displayed.

The first research question explored the relationship between different news topics and the presence of disagreement. Since disagreement only occurs in a small fraction of the dataset, Table 2 presents the distribution of comments containing disagreement in both platforms. A Fisher’s exact test for count data indicates significant differences between the topics that foster expressions of disagreement in each platform. Namely, discussions on Facebook have disagreement in a broader range of topics—being more frequent in response to stories about minorities, followed by formal politics. On news websites, disagreement mainly occurs in stories about formal politics, with very few instances in other topics.

Distribution of disagreement per story topic and platform.

| Story topic | News sources | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Political news | 320 (37.8%) | 472 (81.7%) | Two-sided Fisher’s exact test: <0.0001 |

| Minorities | 421 (49.7%) | 48 (8.3%) | |

| Policy | 84 (9.9%) | 26 (4.5%) | |

| Civic society | 19 (2.2%) | 29 (5%) | |

| International | 3 (0.4%) | 3 (0.5%) | |

| Total | 847 (100%) | 578 (100%) | |

Only column proportions are displayed (percentages per platform).

To address our remaining research questions, we employ predictive modeling using multiple logistic regression, which enables us to investigate a nominal dependent variable (presence of disagreement) in relation to a series of explanatory independent variables, while also controlling for factors such as the platform for each comment (Pampel 2000). An advantage of this approach is that it identifies the strength of the effect of each independent variable in predicting the dependent variable. We built two logistic regression models to predict the presence of disagreement using incivility, intolerance, replies, platform, justified opinion expression, and the topics of the news stories (civic society, minorities, policy-related topics, international affairs; topic of reference: formal politics) as independent variables.9 The second model adds an interaction between justified opinion expression and incivility to address our last research question.

To account for potential differences in comments on popular stories versus less popular ones, we also controlled for the total number of comments in the original story. Log odds (β) were converted to odds ratios (eβ) to facilitate interpretation, and we report confidence intervals in addition to p values. When odds ratios are within the confidence intervals, one can report 95% confidence that the independent variable has the calculated effect on the dependent variable. Table 3 shows the results of both models.

Logistic regression predicting disagreement in online comments.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (eβ) | CI 95% | OR (eβ) | CI 95% | |

| Reply | 51.90*** | [43.42, 62.04] | 51.25*** | [42.91, 61.21] |

| Justified opinions | 3.11*** | [2.66, 3.63] | 4.23*** | [3.44, 5.20] |

| Is uncivil | 2.36*** | [2.04, 2.74] | 3.08*** | [2.55, 3.72] |

| Is Intolerant | 0.87 | [0.66, 1.16] | 0.87 | [0.65, 1.16] |

| 1.57*** | [1.32, 1.86] | 1.57*** | [1.32, 1.86] | |

| Number of comments | 1.00 | [1.00, 1.00] | 1.00 | [1.00, 1.00] |

| News topics: | ||||

| Minorities | 1.86*** | [1.54, 2.25] | 1.88*** | [1.55, 2.28] |

| Policy | 1.29 | [0.98, 1.71] | 1.32 | [1.00, 1.74] |

| Civil society | 1.77** | [1.17, 2.67] | 1.76** | [1.17, 2.66] |

| International | 0.30** | [0.12, 0.73] | 0.30** | [0.12, 0.74] |

| Incivility versus justified opinion | 0.51*** | [0.38, 0.68] | ||

| N | 12,337 | 12,337 | ||

| AIC | 5,099.45 | 5,081.50 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.51 | 0.52 | ||

-

Reference category for topics: Political News.

CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

*** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05.

The first hypothesis theorized a relationship between platform and crosscutting discussion, expecting a higher likelihood of disagreement on comments from news websites when compared to those on Facebook. While the bivariate analysis provided some support to this hypothesis, the results of the regression model are in the opposite direction, suggesting that, after controlling for other factors, comments expressing disagreement were more likely to appear on Facebook than on news websites. Thus, the evidence is mixed, and the first hypothesis is partially confirmed.

The second research question focused on democratically desirable conversational traits and asked whether participants in more heterogeneous debates would be more likely to justify their views. The results suggest a positive and strong relationship between these two variables: in the presence of disagreements, comments are significantly more likely to display efforts to justify opinions and perspectives. Replies also have a positive association, indicating that when participants express diverging opinions, they are significantly more likely to directly engage with others in a discussion.

Our third research question inquired about the association between incivility and disagreement. When participants express disagreement, their comments are over two times more likely to be uncivil than civil, suggesting a strong positive association between these two behaviors. The same is not true for expressions of intolerance, which have a negative, but not significant, association with disagreement—answering the fourth research question.

The last research question explored a relationship between incivility and justified opinion expression in predicting disagreement (Model 2). The significant interaction coefficient suggests that the likelihood of a comment expressing disagreement varies with different levels for incivility (civil/uncivil) and justification (justified/unjustified). To probe these effects, we plotted predicted probabilities for the interaction term (Figure 1) using sjPlot (Lüdecke 2018). Comments that are uncivil and justified have a greater likelihood to contain disagreement than comments that are uncivil and unjustified. Civil and unjustified comments are the least likely to contain disagreement, whereas the presence of justification increases the likelihood of disagreement in civil comments.

Discussion

Exposure to and engagement with disagreement in political discussions are core values in democratic societies, as they enable citizens to understand and respect each other’s views, and to become aware of different perspectives around topics of public concern (Stromer-Galley et al. 2015; Vaccari et al. 2016; Wojcieszak & Mutz 2009). The internet, with its many venues for discussion, fulfills an important role in offering citizens opportunities to be exposed to, and to participate in, heterogeneous conversations (Heatherly, Lu & Lee 2016; Vaccari et al. 2016; Wojcieszak & Mutz 2009).

Everyday political conversation is complex, messy, and unstructured, and as such it may sometimes benefit, and sometimes detract from, deliberation (Maia 2012, 2017; Maia et al. 2020b; Zhang & Chang 2014). Although previous research has been primarily characterized by single-platform studies, this article adopts a comparative perspective to examine the extent to which disagreement happens in more informal discussion platforms online, such as social media, when compared to spaces designed to foster debates, for example, news websites. In doing so, our study contributes to a better understanding of the conditions in which heterogeneous debates occur, both in terms of the discussion features that are associated with it, and in terms of how it is affected by the platform in which participants are discussing. Instead of looking for elusive deliberative values in online political talk, this article focuses on examining discursive characteristics associated with disagreement to understand how everyday political discussions can help promote democratic citizenship.

Based on prior research, we hypothesized that those who comment on news on Facebook would be less likely to engage in disagreement than commenters on news websites, as identification, social cues, and network effects of Facebook could potentially constrain this type of behavior (Ellison & Boyd 2013; Heatherly et al. 2016). Our results were mixed: at the bivariate level the hypothesis was supported, as disagreement was proportionally more frequent on news websites than on Facebook comments. However, when other conversational and contextual features are taken into account in the multivariate analysis, comments on news shared on Facebook were significantly more likely to contain expressions of disagreement, which suggests that Facebook users may not perceive the risks of engaging in heterogeneous debates on social media in a similar way that they do in offline contexts (Mutz 2016). Although it may be surprising that a more anonymous environment is less likely to elicit disagreement given prior research on the effects of anonymity (Chui 2014; Santana 2014; Suler 2004), our results are consistent with Heatherly et al.’s (2016), who finds that SNS users engage with substantial levels of crosscutting discussions. A potential explanation is that Facebook allows its users to maintain large social networks which predominantly consist of weak ties (Ellison & Boyd 2013) and, as such, its users might feel free to express opinions in the context of disagreement because these connections may not represent the same social risks of face-to-face debates. Another explanation is that Facebook users have more ‘conversational control’ (Fox & McEwan 2017)—the ability to manage the mechanics of an interaction, such as entering or leaving a discussion—which may reduce the social costs of disagreement.

We must also consider the role of ‘invisible’ platform affordances, such as Facebook feed algorithms, which rank the comments based on both engagement and ‘relevance to the user’ (Bucher 2017). As a result of algorithmic filtering and ordering, it may be the case that users only see a fraction of the conversation and are not fully aware of what others are saying—which may influence their perception of the public opinion climate (Soffer & Gordoni 2018). Given the nature of our data, we cannot control for how these factors may influence discussion on social media. Finally, it is widely known that Facebook’s feed algorithms privilege stories that elicit engagement over those that do not, which may also mean that its users are more likely to be exposed to controversial stories than those who consume news on regular websites, which would explain a higher probability of heterogeneous discussions on social media. The news sources investigated in this study also did not have features such as voting to order comments at the time of the study.

Even though our results suggest that comments characterized by disagreement are the exception, not the norm, it is important to note that crosscutting debates are significantly more likely to have justified opinion expression than homogeneous conversations. Although our approach did not scrutinize the quality of these justifications, our results indicate that the types of heterogeneous debates that citizens are exposed to and participate in online spaces, such as public social media feeds and news websites, tend to elicit them to elaborate on their opinions—which may promote opinion refinement, as well as awareness of others’ views. Given that research has indicated that political disagreement can be avoided face-to-face (Mutz 2006; Stromer-Galley et al. 2015; Steiner et al. 2017), this study suggests that online platforms may fulfill an important role in the deliberative system by fostering the types of heated debates that citizens may refrain from engaging in offline.

By examining news stories across different political issues and actors, this study demonstrates that some topics are associated with more disagreement than others, and sheds light on the importance of going beyond ‘hard news’ topics when studying online political talk. While our analysis is neither exhaustive of all topics that could be considered political, nor has considered political talk that may occur in discussions about entertainment or sports (see Wright 2012), our findings suggest that comments on stories about social issues, minorities, international affairs, and civil society were significantly more likely to trigger polarized debates—indicating that studies that look at a single issue or topic might provide a limited perspective on the characteristics of online discussion. Importantly, we find that heterogeneous discussions about these broader topics are significantly more likely to take place on Facebook than on news websites, where comments are heavily concentrated around stories about formal politics. In line with research suggesting that those who use social media are more likely to be exposed to diverse news stories and perspectives, our study provides further evidence that social media use may also facilitate discursive engagement with heterogeneous views (Stromer-Galley et al. 2015; Vaccari et al. 2016; Valenzuela & Bachmann 2015; Wojcieszak & Mutz 2009). Furthermore, this work highlights the importance of studying informal discussion spaces that are not specifically designed to talk about politics (Maia & Rezende 2016; Wright 2012).

Our findings suggest that heterogeneous discussions are associated with elevated levels of uncivil discourse, which is not particularly surprising (Papacharissi 2004; Coe et al. 2014). The fact that online debates are, however, characterized by incivility does neither necessarily mean that the environment is toxic for its participants, nor that it nourishes expressions of intolerance which threaten and harm democratic values and as such would undermine any potential benefit of these interactions (Rossini 2019). The positive interaction between incivility and justification suggests that heated rhetoric is not merely an indicator of unproductive conversations or shouting matches. As such, albeit uncivil, these comments might still be beneficial for participants insofar as they expose them to diverse opinions. Nevertheless, it is important to note that uncivil messages have a different appeal for people with distinct personalities. Although those who are conflict oriented enjoy participating in heated discussions and are not negatively affected by incivility, people who avoid conflict may refrain from engaging in these conversations (Sydnor 2019). Thus, even though the pervasiveness of incivility in heterogeneous debates online should not be enough to prevent people from learning about each other’s perspectives and may be seen as entertaining by those who participate in digital debates (Hmielowski et al. 2014; Sydnor 2018), we must recognize that incivility may inhibit some people from joining these conversations—in particular, people who are conflict avoidant. Likewise, it is worth noting that our discussion of the potential harm of uncivil discourse is based on the content of online comments, and not on actual experiences of those who are exposed to or targeted by uncivil remarks.

On the contrary, the finding that expressions of intolerance are not associated with disagreement may indicate that some of the concerns about the quality and the tone of these debates might have been overstated in the past, perhaps as a result of less nuanced approaches to incivility (Papacharissi 2004; Rossini 2019). Similarly, this is consistent with prior research suggesting that extreme opinions are more likely to circulate in homogeneous online forums in which these views are not challenged (Soffer & Gordoni 2018; Wojcieszak 2010, 2011). Being exposed to or targeted by discourse that is racist, harassing, misogynistic, or denotes prejudice can have detrimental effects for both participants and bystanders (Chen et al. 2018; Duggan 2017; Lindsay et al. 2016; Mitchell et al. 2016). The fact that this type of expression is not present in discussions in which opposing views circulate is another indication that heterogeneous online conversations may have intrinsic benefits on their own, regardless of their tone, because they help expose citizens to a broader range of perspectives than they could access otherwise in their offline networks.

While there are many online spaces in which intolerant opinions may circulate, such as discussion groups on Facebook, Gab, 4chan, or Twitter, our study suggests that some of the public and diverse spaces in which people comment on news can be fertile environments for participants to be exposed to and engage with disagreement, particularly because when those conversations do occur they are characterized by justified opinion exchange, allowing for participants and bystanders to better understand the positions at stake. Even if it is true that the tone—in terms of civility—of these discussions is not ideal from a deliberative standpoint, our results suggest that the substance of these debates is not inherently problematic, at least in terms of expressing intolerance.

This study has limitations. First, online discussions in which participants are exposed to political disagreement are not undoubtedly beneficial for democratic societies. Some authors have found that exposure to disagreement online might influence those who lean partisan to seek more homogeneous information, which could contribute to polarization (Weeks et al. 2017). Research on disagreement can benefit from experimental studies to understand how being exposed to or participating in these debates affects citizens. Second, we focus on news media outlets that are fairly traditional and mainstream, and our findings can neither be extended to other types of news sources that citizens might encounter online, nor to other online discussion spaces such as online forums, which may have different conversational dynamics—as well as different affordances—than the ones we studied. Third, our analysis is limited to textual elements, and does not account for graphic expressions such as emojis, gifs, and memes, which are an increasingly important aspect of online political talk. Future research needs to tackle the challenge of understanding how these visual forms of communication are embedded in political talk and how they may affect users’ experiences. Fourth, we argue that incivility is not incompatible with democratically relevant political talk, assuming that participants in online discussions are not deeply offended or feel personally threatened by these expressions. More research is, however, needed to understand how different types of incivility may affect both participants and bystanders in online discussion. Lastly, we have sought to understand the dynamics of intolerant discourse in the context of disagreement but could not find a significant relationship, which could be in part attributed to the rarity of these behaviors in the platforms we analyzed, or due to the fact that they might be systematically moderated—the latter being a structural challenge in research that draws upon publicly available data. Research initiatives in collaboration with media and social media companies, as well as qualitative work focusing on moderation, are needed to further understand how these ‘invisible’ affordances of online platforms affect discussion dynamics.

Conclusion

The contributions of this study can be summarized as follows. First, this article emphasizes the need to look beyond a single platform and a single topic to understand political discussion online and provides further evidence of how platforms shape interpersonal interactions. Second, we show that the topic of a news story is relevant both to drive political conversation and to spark political disagreement, and demonstrate that platforms such as Facebook can amplify exposure to diverse viewpoints in a broader array of political topics, when compared to news websites. As such, our article contributes to a growing body of literature investigating how the use of social networking sites contributes to expose people to more diverse information. Third, we find that crosscutting debates on social media and news websites may provide opportunities for people to learn about others’ opinions insofar as they are characterized by justified opinion expression. Although it cannot be argued that the quality of these debates measure up to the standards of deliberation, the fact that those who engage in heterogeneous online discussions are likely to justify themselves suggests that participating in these debates is a valuable experience that may produce beneficial outcomes—even if users are not open to change their minds. Fourth, we argue that uncivil discourse might be compatible with heated political discussions online and should not undermine their democratic values, as discussions within the deliberative system may not always fulfill the deliberative ideal. Lastly, research on online political talk has been disproportionally focused in the United States and the United Kingdom, with few case studies of non-English speaking countries surfacing internationally. This study contributes to fill an important gap in the literature by examining the Brazilian context and shedding light into how the discussion dynamics in the country are shaped by the different platforms in which citizens can debate politics. Brazil offers a relevant case study given its prominence and population, as it represents the fourth largest digital market worldwide—only behind China, India, and the United States. Thus, the findings of this study contribute to advance our knowledge about how citizens in modern democracies use digital platforms to engage in political conversation beyond English-speaking countries.

Notes

- Data retrieved from Statista in February 5, 2019: https://www.statista.com/topics/2045/internet-usage-in-brazil. ⮭

- Rowe (2015) draws on Papacharissi’s (2004) distinction between politeness and incivility and considers the latter as ‘threats to democratic norms.’ This article takes a different approach, drawing on politeness to define incivility and distinguishing it from democratically threatening behaviors identified as political intolerance. ⮭

- We opted to not differentiate blog articles from other stories because these are professional blogs, written by journalists and columnists, and the rules for moderation in blogs hosted by Portal UOL are the same followed by the platform in news stories. It is thus expected that the content considered inappropriate in news stories by moderators would also be moderated in blogs. ⮭

- Confidence interval: 99%; margin of error: 1%. ⮭

- We calculated Krippendorff’s alpha using a combined sample (news comments and Facebook comments) and separately. In this article, we report the values of the separated samples: disagreement 0.89 (news) and 0.82 (Facebook); incivility 0.87 (news) 0.79 (Facebook); intolerance 0.84 (news) 0.89 (Facebook); opinion expression 0.91 (news); 0.74 (Facebook). ⮭

- We coded messages as being on- and off-topic, with the later representing messages that did not engage with either the topic of the story or another participant in a discussion. This variable was dropped from the analysis, as only 4.8% of the comments were classified as being off-topic. ⮭

- Personal attacks are considered uncivil because while they may be offensive toward an individual, they do not necessarily convey a threat to democratic norms. As well, these are often directed at actors who are not a part of the conversation, and do not necessarily convey interpersonal disrespect. ⮭

- Coders analyzed sequences of messages in each news story, and thus were able to code for disagreement when a comment explicitly disagreed with the previous messages in addition to when participants directly disagreed from others by tagging or replying to them. For example, if two comments criticized a given political party and another commenter subsequently defended the party, this message was coded as disagreement. ⮭

- Given the strong relationship between replies and disagreement, we tested the models removing replies as an independent variable to check if the results would hold. The Pseudo R2 was lower (0.12 for both models). Most results were consistent and in the same direction: positive and significant relationships for justified opinion expression, incivility, and stories about minorities, and negative, significant relationships for stories about international affairs and the interaction term. The difference was that Facebook and stories about civic society were not significant in the model without replies. We examined the variance inflation factor for replies in the model included in the article and it was low (1.29 for model 1, 1.28 for model 2), suggesting that the variable was not problematic, in spite of its explanatory power. ⮭

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jennifer Stromer-Galley and Jeff Hemsley for feedback and advice in several aspects of this project, Thais Choucair for helping with the content analysis, and Stu Shulman for supporting this research with enterprise access to DiscoverText. The authors also thank members of the Research Group on Media and Public Sphere (EME/UFMG) and the anonymous referees for their suggestions for improving this article. Any remaining issues or shortcomings are our own.

Funding Information

This study was supported in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001 through a doctorate scholarship to Dr. Rossini.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author Information

Patricia Rossini, PhD in Communication (Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil) is an inaugural Derby Fellow in the Department of Communication and Media at the University of Liverpool. Her research in online political talk, uncivil and intolerant discourse, and misinformation has been funded by social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, and by the Knight Foundation. Her work has been published by Communication Research, New Media & Society, Political Studies, Social Media+Society, the International Journal of Communication, and the Journal of Information, Technology & Politics.

Rousiley C. M. Maia, PhD in Political Science (University of Nottingham, UK), is a Professor of Political Communication in the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil. She is the author of Deliberation across deeply divided societies (with J. Steiner, M. C. Jaramillo, and S. Mameli, Cambridge University Press, 2017), Recognition and the media (2014, Palgrave Macmillan), and Deliberation, the media and political talk (2012, Hampton Press). Some of her recent publications have appeared in European Political Science Review, Political Studies, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Journal of Human-Communication Research, Journal of Communication, Representation, Journal of Political Power, Journal of Public Deliberation, and in several Brazilian journals.

References

1 Anderson, A. A., Brossard, D., Scheufele, D. A., Xenos, M. A., & Ladwig, P. (2014). The “nasty effect:” Online incivility and risk perceptions of emerging technologies: crude comments and concern. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(3), 373–387. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12009

2 Anspach, N. M. (2017). The new personal influence: How our Facebook friends influence the news we read. Political Communication, 34(4), 1–17. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1316329

3 Bakshy, E., Messing, S., & Adamic, L. A. (2015). Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook. Science, 348(6239), 1130–1132. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa1160

4 Barber, B. (2003). Strong democracy: Participatory politics for a new age (20th ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

5 Barnidge, M. (2017). Exposure to political disagreement in social media versus face-to-face and anonymous online settings. Political Communication, 34(2), 302–321. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2016.1235639

6 Barnidge, M. (2018). Social affect and political disagreement on social media. Social Media + Society, 4(3). DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118797721

7 Benson, T. W. (2011). The rhetoric of civility: Power, authenticity, and democracy. Journal of Contemporary Rhetoric, 1(1), 22–30.

8 Black, L. W., Burkhalter, S., Gastil, J., & Stromer-Galley, J. (2010). Methods for analyzing and measuring group deliberation. In E. P. Bucy & R. L. Holbert (Eds.), Sourcebook for political communication research: Methods, measures, and analytical techniques. Hoboken, NJ: Taylor & Francis.

9 Brundidge, J. (2010). Encountering “difference” in the contemporary public sphere: The contribution of the internet to the heterogeneity of political discussion networks. Journal of Communication, 60(4), 680–700. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01509.x

10 Bucher, T. (2017). The algorithmic imaginary: Exploring the ordinary affects of Facebook algorithms. Information, Communication & Society, 20(1), 30–44. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1154086

11 Chen, G. M., Pain, P., Chen, V. Y., Mekelburg, M., Springer, N., & Troger, F. (2018). ‘You really have to have a thick skin’: A cross-cultural perspective on how online harassment influences female journalists. Journalism, 21(7), 877–895. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918768500

12 Chui, R. (2014). A multi-faceted approach to anonymity online: Examining the relations between anonymity and antisocial behaviour. Journal for Virtual Worlds Research, 7(2). DOI: http://doi.org/10.4101/jvwr.v7i2.7073

13 Coe, K., Kenski, K., & Rains, S. A. (2014). Online and uncivil? Patterns and determinants of incivility in newspaper website comments. Journal of Communication, 64(4), 658–679. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12104

14 Coleman, S., & Blumler, J. G. (2009). The internet and democratic citizenship: Theory, practice and policy (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511818271

15 Coleman, S., & Moss, G. (2012). Under construction: The field of online deliberation research. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 9(1), 1–15. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2011.635957

16 Connolly-Ahern, C., Ahern, L. A., & Bortree, D. S. (2009). The effectiveness of stratified constructed week sampling for content analysis of electronic news source archives: AP newswire, business wire, and PR newswire. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 86(4), 862–883. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/107769900908600409

17 Conover, P. J., & Searing, D. D. (2005). Studying ‘everyday political talk’ in the deliberative system. Acta Politica, 40(3), 269–283. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500113

18 Crawford, J. T., & Pilanski, J. M. (2014). Political intolerance, right and left. Political Psychology, 35(6), 841–851. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2012.00926.x

19 Dewey, J. (1927). The public and its problems: An essay in political inquiry. New York: Holt.

20 Duggan, M. (2017). Online Harassment 2017. Pew Research Center, Washington, DC. http://www.pewinternet.org/2017/07/11/online-harassment-2017.

21 Ellison, N. B., & Boyd, D. M. (2013). Sociality through social network sites. In W. H. Dutton (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of internet studies (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199589074.013.0008

22 Esterling, K. M., Fung, A., & Lee, T. (2015). How much disagreement is good for democratic deliberation? Political Communication, 32(4), 529–551. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2014.969466

23 Eveland, W. P. (2004). The effect of political discussion in producing informed citizens: The roles of information, motivation, and elaboration. Political Communication, 21(2), 177–193. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10584600490443877

24 Eveland, W. P., & Hively, M. H. (2009). Political discussion frequency, network size, and “heterogeneity” of discussion as predictors of political knowledge and participation. Journal of Communication, 59(2), 205–224. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2009.01412.x

25 Fox, J., & McEwan, B. (2017). Distinguishing technologies for social interaction: The perceived social affordances of communication channels scale. Communication Monographs, 84(3), 298–318. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1332418

26 Freelon, D. (2013). Discourse architecture, ideology, and democratic norms in online political discussion. New Media & Society, 17(5), 772–791. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813513259

27 Garrett, R. K., Carnahan, D., & Lynch, E. K. (2013). A turn toward avoidance? Selective exposure to online political information, 2004–2008. Political Behavior, 35(1), 113–134. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-011-9185-6

28 Gervais, B. T. (2014). Incivility online: Affective and behavioral reactions to uncivil political posts in a web-based experiment. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 12(2), 1–19. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2014.997416

29 Gibson, J. L. (1992). The political consequences of intolerance: Cultural conformity and political freedom. American Political Science Review, 86(2), 338–356. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/1964224

30 Gil de Zúñiga, H., Jung, N., & Valenzuela, S. (2012). Social media use for news and individuals’ social capital, civic engagement and political participation. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 17(3), 319–336. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2012.01574.x

31 Graham, T. (2012). Beyond “political” communicative spaces: Talking politics on the wife swap discussion forum. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 9(1), 31–45. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2012.635961

32 Gutmann, A., & Thompson, D. (1996). Democracy and disagreement. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674197664.

33 Habermas, J. (1996). Between facts and norms: Contributions to a discourse theory of law and democracy. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/1564.001.0001

34 Halpern, D., & Gibbs, J. (2013). Social media as a catalyst for online deliberation? Exploring the affordances of Facebook and YouTube for political expression. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 1159–1168. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.008

35 Heatherly, K. A., Lu, Y., & Lee, J. K. (2016). Filtering out the other side? Cross-cutting and like-minded discussions on social networking sites. New Media & Society, 19(8), 1271–1289. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816634677

36 Hester, J. B., & Dougall, E. (2007). The efficiency of constructed week sampling for content analysis of online news. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 84(4), 811–824. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/107769900708400410

37 Hmielowski, J. D., Hutchens, M. J., & Cicchirillo, V. J. (2014). Living in an age of online incivility: Examining the conditional indirect effects of online discussion on political flaming. Information, Communication & Society, 17(10), 1196–1211. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.899609

38 Hong, Y., & Rojas, H. (2016). Agreeing not to disagree: Iterative versus episodic forms of political participatory behaviors. International Journal of Communication, 10, 1743–1763.

39 Huckfeldt, R., & Mendez, J. M. (2008). Moths, flames, and political engagement: Managing disagreement within communication networks. The Journal of Politics, 70(01), 83–96. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381607080073

40 Lindsay, M., Booth, J. M., Messing, J. T., & Thaller, J. (2016). Experiences of online harassment among emerging adults: Emotional reactions and the mediating role of fear. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31(19), 3174–3195. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515584344

41 Lüdecke, D. (2018). sjPlot—Data Visualization for Statistics in Social Science. Zenodo. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.1308157

42 Maia, R. C. M. (2012). Deliberation, the media and political talk. New York: Hampton Press.

43 Maia, R. C. M. (2014). Recognition and the media. London: Palgrave Macmillan. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1057/9781137310439

44 Maia, R. C. M. (2017). Politicization, new media, and everyday deliberation. In P. Fawcett, M. Flinders, C. Hay, & M. Wood (Eds.), Anti-politics, depoliticization, and governance (pp. 68–90). Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198748977.003.0004

45 Maia, R. C. M. (2018). Deliberative media. In A. Bächtiger, J. S. Dryzek, J. Mansbridge, & M. E. Warren (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of deliberative democracy (pp. 348–364). Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198747369.013.11

46 Maia, R. C. M., & Rezende, T. A. S. (2016). Respect and disrespect in deliberation across the networked media environment: Examining multiple paths of political talk: Disrespect in deliberation across digital settings. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 21(2), 121–139. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12155

47 Maia, R. C. M., Cal, D., Bargas, J., & Crepalde, J. C. (2020). Which types of reason-giving and storytelling are good for deliberation? European Political Science Review. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773919000328

48 Maia, R. C. M., Hauber, G., Choucair, T., & Crepalde, N. J. (2020). What kind of disagreement favors reason-giving? Analyzing online political discussions across the broader public sphere. Political Studies, 69(1), 108–128. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719894708

49 Mansbridge, J. (1999). Everyday talk in the deliberative system. In S. Macedo (Ed.), Deliberative politics: Essays on democracy and disagreement (pp. 1–211). New York: Oxford University Press.

50 Mitchell, K. J., Ybarra, M. L., Jones, L. M., & Espelage, D. (2016). What features make online harassment incidents upsetting to youth? Journal of School Violence, 15(3), 279–301. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2014.990462

51 Moy, P., & Gastil, J. (2006). Predicting deliberative conversation: The impact of discussion networks, media use, and political cognitions. Political Communication, 23(4), 443–460. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10584600600977003

52 Mutz, D. (2006). Hearing the other side: Deliberative versus participatory democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511617201

53 Neblo, M. (2005). Thinking through democracy: Between the theory and practice of deliberative politics. Acta Politica, 40(2), 169–181. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500102

54 Neuendorf, K. A. (2002). The content analysis guidebook (1st ed.). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

55 O’Sullivan, P. B., & Flanagin, A. J. (2003). Reconceptualizing ‘flaming’ and other problematic messages. New Media & Society, 5(1), 69–94. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1461444803005001908

56 Pampel, F. C. (2000). Logistic regression: A primer (vol. 132). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4135/9781412984805

57 Papacharissi, Z. (2004). Democracy online: Civility, politeness, and the democratic potential of online political discussion groups. New Media & Society, 6(2), 259–283. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1461444804041444

58 Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: what the internet is hiding from you. London: Penguin Press.

59 Parkinson, D. J., & Mansbridge, P. J. (Eds.) (2012). Deliberative systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139178914

60 Rossini, P. (2019). Disentangling uncivil and intolerant discourse. In R. Boatright, T. Shaffer, S. Sobieraj, & D. G. Young (Eds.), A crisis of civility? Contemporary research on civility, incivility, and political discourse (pp. 142–157). New York: Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781351051989-9

61 Rowe, I. (2015). Civility 2.0: A comparative analysis of incivility in online political discussion. Information, Communication & Society, 18(2), 121–138. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.940365

62 Santana, A. D. (2014). Virtuous or vitriolic: The effect of anonymity on civility in online newspaper reader comment boards. Journalism Practice, 8(1), 18–33. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2013.813194

63 Scheufele, D. A., Nisbet, M. C., Brossard, D., & Nisbet, E. C. (2004). Social structure and citizenship: Examining the impacts of social setting, network heterogeneity, and informational variables on political participation. Political Communication, 21(3), 315–338. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10584600490481389

64 Shah, D. V. (2016). Conversation is the soul of democracy: Expression effects, communication mediation, and digital media. Communication and the Public, 1(1), 12–18. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/2057047316628310

65 Sobieraj, S., & Berry, J. M. (2011). From incivility to outrage: Political discourse in blogs, talk radio, and cable news. Political Communication, 28(1), 19–41. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2010.542360

66 Soffer, O., & Gordoni, G. (2018). Opinion expression via user comments on news websites: Analysis through the perspective of the spiral of silence. Information, Communication & Society, 21(3), 388–403. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1281991

67 Steiner, J. (2012). The foundations of deliberative democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139057486

68 Steiner, J., Jaramillo, M. C., Maia, R. C. M., & Mameli, S. (2017). Deliberation across deep divisions: Transformative moments. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

69 Stromer-Galley, J. (2007). Measuring deliberation’s content: A coding scheme. Journal of Public Deliberation, 3(1), 12. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.50

70 Stromer-Galley, J., Bryant, L., & Bimber, B. (2015). Context and medium matter: Expressing disagreements online and face-to-face in political deliberations. Journal of Public Deliberation, 11(1), 1. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.218

71 Stromer-Galley, J., & Wichowski, A. (2011). Political discussion online. In M. Consalvo & C. Ess (Eds.), (vol. 11, pp. 168–187). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/9781444314861.ch8

72 Stroud, N. J., Scacco, J. M., Muddiman, A., & Curry, A. L. (2014). Changing deliberative norms on news organizations’ Facebook sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20(2), 188–203. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12104

73 Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7(3), 321–326. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1089/1094931041291295

74 Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Republic.com 2.0. Oxford: Princeton University Press.

75 Sydnor, E. (2018). Platforms for incivility: Examining perceptions across different media formats. Political Communication, 35(1), 97–116. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1355857

76 Sydnor, E. (2019). Disrespectful democracy: The psychology of political incivility. New York: Columbia University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7312/sydn18924

77 Turner, D. D. (2010). Comments gone wild: Trolls, frames, and the crisis at online newspapers. mimeo. Retrieved from http://twoangstroms.com/s/CrisisInCommenting.pdf.

78 Vaccari, C., Valeriani, A., Barberá, P., Jost, J. T., Nagler, J., & Tucker, J. A. (2016). Of echo chambers and contrarian clubs: Exposure to political disagreement among German and Italian users of twitter. Social Media+ Society, 2(3). DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116664221

79 Valenzuela, S., & Bachmann, I. (2015). Pride, anger, and cross-cutting talk: A three-country study of emotions and disagreement in informal political discussions. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 27(4), 544–564. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edv040

80 Valenzuela, S., Kim, Y., & Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2012). Social networks that matter: Exploring the role of political discussion for online political participation. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 24(2), 163–184. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edr037

81 Walsh, K. C. (2003). Talking about politics: Informal groups and social identity in American life (1st ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226872216.001.0001

82 Weeks, B. E., Lane, D. S., Kim, D. H., Lee, S. S., & Kwak, N. (2017). Incidental exposure, selective exposure, and political information sharing: Integrating online exposure patterns and expression on social media. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 22(6), 363–379. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12199

83 Wojcieszak, M. (2010). ‘Don’t talk to me’: Effects of ideologically homogeneous online groups and politically dissimilar offline ties on extremism. New Media & Society, 12(4), 637–655. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809342775

84 Wojcieszak, M. (2011). Pulling toward or pulling away: Deliberation, disagreement, and opinion extremity in political participation. Social Science Quarterly, 92(1), 207–225. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2011.00764.x

85 Wojcieszak, M. E., Baek, Y. M., & Carpini, M. X. D. (2010). Deliberative and participatory democracy? Ideological strength and the processes leading from deliberation to political engagement. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 22(2), 154–180. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edp050

86 Wojcieszak, M., & Mutz, D. (2009). Online groups and political discourse: Do online discussion spaces facilitate exposure to political disagreement? Journal of Communication, 59(1), 40–56. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.01403.x

87 Wojcieszak, M., & Price, V. (2010). Bridging the divide or intensifying the conflict? How disagreement affects strong predilections about sexual minorities. Political Psychology, 31(3), 315–339. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2009.00753.x

88 Wojcieszak, M., & Price, V. (2012). Perceived versus actual disagreement: Which influences deliberative experiences? Journal of Communication, 62(3), 418–436. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01645.x

89 Wright, S. (2012). From “third place” to “third space”: Everyday political talk in non-political online spaces. Javnost – The Public, 19(3). DOI: http://javnost-thepublic.org/article/2012/3/1/

90 Xenos, M., & Moy, P. (2007). Direct and differential effects of the internet on political and civic engagement. Journal of Communication, 57(4), 704–718. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00364.x

91 Zhang, W., & Chang, L. (2014). Perceived speech conditions and disagreement of everyday talk: A proceduralist perspective of citizen deliberation: Perceived speech conditions and disagreement. Communication Theory, 24(2), 124–145. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12034