In the largest sense, this study is motivated by macro level concerns about the ‘crisis of democracy’ in the 21st century and the potential for deliberative practices to mitigate that crisis (Dryzek et. al. 2019). That crisis has been diagnosed by an internationally representative group of scholars of deliberation as an ‘overload’ of opportunities for citizens to have their voices heard ‘accompanied by marked decline in civility and argumentative complexity’ (Dryzek et al. 2019: 1144). They assert that polarization and incivility have an impact on civic participation and willingness to engage with ideas other than one’s own. Furthermore, a reliance on simple arguments and simple proposals for complex problems leads to susceptibility by citizens to ill-reasoned, populist, and increasingly authoritarian appeals from political elites (Dryzek et al. 2019). Although the real world of politics today is far from a deliberative ideal, these scholars argue that there is increasing empirical evidence that deliberative practices, programs, and structures offer some ways to alleviate this crisis.

Although motivated by ‘macro’ level concerns, the study presented here focuses on ‘micro-level’ impacts of the deliberative experience on individuals (Kuyper 2018). We examine whether structured experience in deliberation, in a college setting, during emerging adulthood might promote longer term cognitive and communicative characteristics, such as more complex thinking about one’s role as a citizen and more interest and willingness to communicate about politics across difference after college graduation. We argue that complexity of thinking, together with behavioral openness and ability to communicate about potentially divisive issues, are essential civic skills, skills that are especially needed in the current political climate.

Why Emerging Adulthood?

Emerging adulthood (i.e. 18–25 years of age) should be a fruitful period in which to influence the development of civic skills and motivations. By late adolescence or early emerging adulthood, cognitive skills for abstraction, consideration of multiple perspectives, and nuanced problem-solving are typically present (Flanagan 2004; Wray-Lake & Flanagan 2012). Furthermore, in industrialized countries, emerging adulthood is an important time for the formation of identity, which involves attending to, reflecting on, and trying out alternative possibilities (e.g. Erikson 1968; McLean & Syed 2016). Education and experiences that promote ways of thinking and behaving about civic concerns during this time thus have the potential for longer term influence, in part because in the process of identity development, individuals aim to create a coherent sense of self that integrates their values, beliefs, and behavior over time (e.g. McLean & Syed 2016). Therefore, we expected that emerging adults who engage in experiences that promote complex thinking and perspective-taking about challenging and potentially divisive civic issues, or that promote the skills and motivation for communicating across differences, would be likely to carry those skills and inclinations into young adulthood. We expected that deliberative dialogue would be one of those experiences.

Why Deliberation?

The body of empirical evidence is growing, particularly in studies of the impact of deliberative experiences at the individual and group level, that demonstrates that deliberation done well can contribute to development of civic skills that are valued in democratic theory. In an extensive review of this literature, Kuyper (2018) notes that changes found at the individual level include increased knowledge of issues and increased willingness to participate in politics and engage in one’s community. Observational studies of groups engaged in deliberation find that participants learn about the views of others with whom they disagree, which has a depolarizing or “debiasing” effect on the group (Gronlund et al. 2010; Colombo 2018). Elements of the deliberative process, such as recognizing one’s own values and biases, considering alternative points of views, and justifying one’s opinions to others, have shown promise in reducing intergroup hostility in post-conflict societies (Boyd-MacMillan et. al. 2016) and in divisive public debates (Colombo 2018). ‘There is now considerable evidence,’ writes Kuyper, ‘that deliberation produces other-regardingness and inhibits polarization’ (p. 11).

For the purposes of this study, deliberative dialogue is defined as a process in which participants ‘carefully examine a problem and arrive at a well-reasoned solution after a period of inclusive, respectful consideration of diverse points of view’ (Gastil 2008: 8). Our subjects were exposed to the National Issues Forum model of deliberative dialogue, which involves a trained moderator who guides the participants through a deliberation on a pressing public issue. Prior to the deliberation, participants have read a prepared issue guide that identifies the problems and disagreements at the root of the issue and offers multiple perspectives on how to resolve the issue. In the deliberation, participants begin with an agreement on ground rules; move to personal storytelling to connect their experiences with the discussion and help the group understand their perspective on the issue; consider each of the alternative approaches as to both benefits and tradeoffs as well as the underpinning values; and conclude by discussing where there is common ground for action and where disagreement continues to exist (National Issues Forum Institute 2002).

The ‘solution’ that emerges often resembles a well-reasoned, now better understood, roadmap of the problem going forward, and some shared impetus to continue the conversation. Participants are asked to consider what they can and are willing to do about the problem in their corner of the world, and also to consider individuals not present with them, but very much affected by the problem: what would they say? (National Issues Forums Institute 2002). Research demonstrates that the elements of a deliberative process in this model are important in overcoming the potential for ‘group think’, or the tendency for unstructured group discussion to move to more extreme positions (see, for example, Landemore and Mercier 2012). Although there are numerous models of deliberation available, the NIFI model used in this study is appealing for its alignment with current thinking concerning the importance of ‘deliberative conversational norms’ (Jennstal 2019; Kuyper 2018).

The impact of deliberation on attitudes and behavior has been studied now in multiple contexts, including in classrooms and higher education (Dedrick, Grattan, & Dienstfrey 2008; Hess 2009), and in communities and across the world (Niemeyer 2011; Nabatchi 2010b, 2010a; Nabatchi, Gastil, Leighninger & Weiksner 2012). A task force convened by the Obama administration concluded that research thus far suggests deliberative dialogue is a high impact methodology for preparing students for their civic roles (National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement 2012). Experiences in ‘discursive participation’ (Jacobs et al. 2009: 3) and opportunities to engage with others whose perspectives are different from one’s own (Cramer & Toff 2017) have been shown to promote many aspects of civic engagement. These scholars have argued that such experiences are essential to civic competence in our current fractured media environment and polarized politics, and ‘can act as a pathway to more informed, reasoned, and active engagement in public life’ (Jacobs et al. 2009: 158). Both theory and evidence, then, strongly suggest that deliberation, when its purposes are explained and it is practiced over time, should be regarded as more than a practical problem-solving tool: it can be a high impact method for teaching individuals to reason, with others, more mindfully, about the complex issues of social and political life.

Why Cognitive Complexity?

The concept of cognitive complexity, which has been explored extensively in the field of political psychology, reflects a cognitive approach that cares about, understands, and integrates multiple perspectives. It has been used in analyzing the public statements of political leaders (Suedfeld 2010), but has application well beyond elites. It has also been used to assess the impact of various life experiences on average citizens and students of various ages (see, for example, Hunsberger et al. 1992; Suedfeld et al. 1994; Flanagan et al. 2014; Pancer et al. 2000a, 2000b).

If the current political environment discourages complexity of arguments and increases susceptibility to simplistic and polarized solutions offered by demagogues (Dryzek et al. 2019), then learning to reason through complex, nuanced issues can serve as an antidote and an important civic skill. Therefore, interventions that increase the likelihood that participants might think in complex ways about political issues suggest a promising approach to equipping citizens for this environment. Research suggests that experiences that challenge a person’s worldview, or create dissonance between a person’s beliefs and new information, can lead to more cognitively complex judgments as a way of resolving the tension. This is particularly true when individuals are being held accountable by audiences that contain both points of view (Tadmor & Tetlock 2006; Tetlock 1986, 1992). For example, Colombo (2018) found that telling study participants that they would be required to justify their position in a group discussion had a significant impact on how ‘considered’ their opinions were. A ‘considered’ opinion was ‘one that integrated arguments of different sides and could be well justified by substantive reason’ (p. 25). Similarly, Hunberger et al. (1992) found that research subjects who were prompted to think in more complex ways were able to do so. Furthermore, when adolescents and young adults have opportunities, in school or in their own families, to discuss and to debate current events, including national and global issues, they demonstrate more complex thinking about social and political issues (Ballard et al. 2015; Flanagan et al. 2014; Marzana et al. 2012). Such experiences likely expose them to multiple and diverse perspectives and give them practice recognizing and integrating these different perspectives.

Scholars of deliberation have begun to report evidence supporting its impact on cognitive complexity. For example, interventions aimed at enhancing cognitive complexity in post-conflict societies and communities that were deeply divided along racial or ethnic lines found that the deliberative experience “enabled shifts from rapid, inflexible, closed thinking toward more deliberate, flexible, open thinking” by the participants (Boyd-MacMillan et al, 2016, p. 115). Jennstal (2019) assessed the impact of deliberating on attitudes toward street begging in Sweden and found greater complexity of thought following deliberation.

Jennstal argues additionally that ‘integrative complexity scoring’ is a good technique for measuring the impact of deliberation because of the ‘conceptual closeness’ of cognitive complexity and ‘deliberative conversational norms’ (p. 65). She notes that while deliberative democratic theory and cognitive complexity differ in that the first is a ‘normative ideal’ and the second a ‘psychological construct’, they both ‘draw attention to individuals’ capacities to cope with ambiguous and uncertain information, to acknowledge the legitimacy of competing perspectives, to recognise nuances, and to force conceptual links among various perspectives’ (Jennstal 2019: 65). Integrative complexity scoring assesses ‘dialectical complexity’, defined as ‘an attitude of openness to new information’. The scoring process is based on identification of ‘markers of ambiguity, uncertainty, or a willingness to see multiple perspectives as valid’ (Conway et al. 2014: 605). Individuals with higher integrative complexity scores are able to identify the relationships or interactions between elements and to assemble diverse parts of a complicated issue into a coherent and meaningful whole. Neuman (1981) sees this ability to both differentiate the different ways in which a problem might be addressed and also integrate them into a novel solution as a sign of ‘political sophistication’ (p. 1241). This approach to defining and measuring has been used in several studies (e.g. Flanagan et al. 2014; Hunsberger et al. 1992; Jennstal 2019), and is the measure we relied on in our study.

The Current Study

All of this research suggests that college students who are taught the theoretical justifications for deliberation and provided extensive opportunities to deliberate might demonstrate more cognitive complexity in their thinking about their civic role and politics than those who do not, even when all of them have had a similar liberal arts education. It also points to the possibility of developing other civically valuable capacities, especially the willingness to engage with people with whom they disagree (Cramer & Toff 2017). Support for these possibilities emerged in an earlier study comparing such students at college graduation (Harriger & McMillan 2007). In the study we report here, we examine whether any such impact could be seen ten years after graduation. To set the stage for this analysis, we first explain the deliberative experience we engaged in with the study groups and results at the point of college graduation.

The Deliberative Experience: Four Years of Deliberation Practice

The original study was conducted between 2001–2005 and involved 30 students enrolled in a private liberal arts college. An invitation to apply for what was called the Democracy Fellows program was sent to all students who had been accepted for the class entering in the fall of 2001. The application asked students about their most meaningful high school activities, their conceptions of citizenship and their role in civic life, and various demographic information including gender, race, region, and partisan identity (if any). We received applications from 70 students and selected 30 (a number determined by how many seats were available in the two First Year Seminars that would be part of the program). We used the application questions as means to ensure that we had not recruited a group of already fully committed politically-minded students, although we did select a few from that category. The group included students with a wide range of primary interests that included music and the arts, science, and business. Students do not declare majors until their junior year, but we also considered what they anticipated their major might be in order to have a diverse group. In addition, we used data from our admissions office on the demographic makeup of the overall entering class to ensure that the group was representative in this way. Each year of the study we compared the Democracy Fellows (DF) students to a randomly selected class cohort (CC) with data gathered from focus groups and surveys.

Any study of a program’s impact that is based on voluntary participation risks the potential for selection bias. We recognized this from the start of the study and took a number of precautions to try to minimize the extent to which the entering characteristics of the participants could explain the differences we might find later between DFs and CCs. As explained above, we took special care with the application and selection process. For the control group we sent invitations to a randomly selected group from the same class. As with the DFs, the CCs also involved voluntary participation. We used similar language in inviting the cohort as we had used to invite DF applicants. Consequently, we would expect the possible selection bias of people interested in talking about politics and communication to be similar in both groups.

The DFs were enrolled in a First Year Seminar entitled Democracy and Deliberation in which they studied historical documents that underpin American democracy, deliberative democratic theory and its critics, and communication literature on group theory and interaction. Following this grounding in theory, students practiced deliberation through three National Issues Forum issue books. We ended the semester with an exercise in framing a campus issue for deliberation. During the sophomore year DFs organized and moderated a campus-wide deliberation on the issue they had framed the previous year. In their junior year they organized and moderated a community-wide deliberation on urban sprawl. During their senior year they honed their moderating skills in other campus and community settings. Each year the effects of participation in these activities were assessed in various ways: individual interviews, focus groups with DFs and CCs, and surveys measuring activities and time use of both groups. Finally, several questions were embedded in an exit survey given to the whole graduating class of 2005, which allowed us to compare the DFs and CCs to the larger group.

Upon graduation, there were clear differences between the DFs and CCs, despite the fact that other than the DF program, all students had received a similar liberal arts education. Compared to the cohort group, the DFs were more engaged in political activities during college, had more communal (v. self-interested) notions of why one would engage in politics, and spoke in more complex ways about citizenship and its responsibilities. We did not use integrative complexity scoring in the first study, but did do content analysis of focus group transcripts to discern these differences. The fact that their views grew apart over the four years after starting out very much alike suggests program impact.

Is There Evidence of Longer-Term Impact?

To examine whether four years of deliberative experience might have a longer-term impact on emerging adult development, and to probe more deeply the possibility of impact on cognitive complexity suggested in the responses of DFs as they graduated, we conducted a follow-up study ten years after the students’ college graduation. We interviewed and surveyed 20 original DFs, now adults, and 20 of their peers (a Cohort Control, or CC) from the same graduating class who had not had deliberation training. We assessed their views of citizenship with respect to content as well as cognitive complexity, using integrative complexity scoring. We also assessed the extent to which they communicated about politics, including with others who held different political perspectives. We tested hypotheses that the DFs’ sustained experience in deliberative dialogue during emerging adulthood would predict: (a) more complex thinking about citizenship and its responsibilities; and (b) more communication about politics, including across differences.

As with the earlier study, selection bias was possible, but should have been minimized by the manner of recruitment previously described. For the alumni follow-up study reported here, we had the additional ability to match the cohort by majors. This allowed us greater confidence that the differences we found were not explained by differences in interests or abilities entering the program.

Methods

Participants

Participants were two groups of young adults who had graduated from the same liberal arts college ten years before. Twenty of them had participated in a four-year program entitled Democracy Fellows (DF) while in college and had extensive exposure to deliberative theory and practice. The control group (CC) were from the same graduating class (2005) but were not exposed to the program. The CCs were identified from a list obtained from the alumni office, randomly selected through a random number generator matching the control groups’ characteristics to those of the Democracy Fellows in terms of race and ethnicity, gender, and college major. Research on selecting control groups in quasi-experimental designs such as the present one shows that matching on demographic variables strengthens the ability to draw conclusions about the effect of the treatment (Ho, Imai, King, & Stuart 2007). In our attempts to obtain a matched control group while also keeping selection of CC members random, we ended up talking with a larger group of CCs (25) than DFs (20); We selected 20 CCs based on providing the best demographic match to the DFs. Our final sample thus consisted of 40 participants (20 DFs and 20 CCs). Both groups had the exact same breakdown in gender (50% female) and college major (35% Political Science, 15% each History and Business, 10% English, and 6% each Psychology, Philosophy, Economics, Religion, and Spanish). The groups differed slightly in race/ethnicity (DFs = 65% White; CCs = 70% White).

Procedure

Both groups were told that we hoped to learn whether and how college experiences influence young adults’ social views and civic engagement, and that we were interviewing alumni of the 2005 class. All members of both groups participated in a phone interview of approximately one hour. All interviews with DFs were conducted by researchers who had not worked with the DFs while they were in the program. They were each asked the same set of questions. After completing the phone interview participants received a link to an on-line survey that included a measure of communication about politics.

Measures

Integrative Complexity Scoring

As we have noted, integrative complexity is commonly used to assess the structure of thought, regardless of content (Suedfeld et al. 1992). Specifically, it measures the existence of two cognitive components mentioned earlier: differentiation and integration. Differentiation entails the ability of the research subject to identify different dimensions of an issue and to recognize that there is more than one way to see an issue. Integration involves the ability to identify the relationships or interactions between those dimensions, and to recognize tensions and tradeoffs. The highest integrative complexity scores are earned by those who can imagine novel solutions to complex problems through the integration of the multiple dimensions of the issue. Although the length of answers is correlated with complexity, it is possible for lengthy answers to be devoid of differentiation or integration. We were trained by an expert in integrative complexity scoring using the standard training materials (Baker-Brown, Ballard, Bluck, deVries, Suedfeld, & Tetlock 1990). The expert trainer also scored a sample of our data, and we used his scores as a yardstick for practicing as a group on scoring our data. Once we were confident that we understood the method and had reliability in the group, two trained graduate research assistants coded all of the data for the two questions that we used for the analysis. One of the lead researchers served as an outside coder who reviewed and checked answers that the primary coders were uncertain about. One of the graduate student coders had no knowledge of our hypotheses about potential differences between DFs and CCs. Inter-coder reliability for the two primary coders was 0.96.

We scored two questions from the interview: What does citizenship mean to you? and What do you think are the responsibilities of citizenship? We chose these questions for the integrative complexity analysis for several reasons. First and foremost, concepts of citizenship can range from very simplistic (‘If you’re born here, you’re a citizen’) to very complex, involving the differentiation and integration of rights and responsibilities. Second, a central aim of the original study was to aid students in thinking more deeply about citizenship and their personal civic responsibilities. Of the lengthy interview transcript, those two questions were integral to that pursuit. Third, asking about citizenship does not require knowledge of a particular topic (e.g. homelessness), nor should it elicit partisan views in the way a topical question might. It is a neutral and important concept that would seem to apply equally to all participants. The coders were blind to whether the response they were coding was from a DF or a CC. We averaged each participant’s scores for the two questions; thus, our analyses compared the average integrative complexity scores across these two questions for DFs and CCs.

Qualitative Data

In addition to analyzing integrative complexity on the two citizenship questions, we did content analysis of the same two questions. In order to develop our qualitative codes or themes, two members of our team first read through all the interviews to detect any themes that arose within sets of questions. Then these team members proposed an initial set of codes for each group of questions, which the team revised together. After making suggested changes, two team members used the codes on 20 interviews to see if there were any codes we needed to add, delete, or amend. Concerns were discussed with the entire research team if necessary. Once we felt confident in our list of codes, these two team members coded all interview responses using MAXQDA, a software designed for qualitative coding and analyses.

Reliability was obtained based on inter-coder agreement. MAXQDA calculates inter-coder agreement using the following formula: % agreement = # of agreements/(# of agreements + # of non-agreements). For all questions, this reliability calculation was based on the codes from 20 interviews, which were coded by both coders. Following a calculation of reliability for the first 20 interviews, the coders discussed and resolved any differences. Next, each coder completed 10 more interviews independently. The reliability of coding for the citizenship questions was 90.7%.

Communication About Politics

In the online survey, participants rated their agreement with four statements assessing communication about politics on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree). The items were adapted from previous work with adolescents and emerging adults that provided evidence for their validity and reliability (Flanagan et al. 2007; Kahne et al. 2005). The four items were ‘I talk to other people about politics’; ‘I’m interested in other people’s opinion about politics, even if those opinions are different from my views’; ‘I encourage others to express their opinions about politics, even if those opinions are different from my views’; and ‘I am interested in talking about politics and political issues’. Cronbach’s alpha for these items was 0.87.

Results

Integrative Complexity

Scoring

To demonstrate the contrast between lower and higher integrative complexity scores, Table 1 offers examples of responses to the first question: What does citizenship mean to you? Scores can range from 1–7. However, we had no 6 or 7 scores for either question, which we attribute to the fact that these were oral rather than written responses.

Sample Responses for Integrative Complexity Score on “What does citizenship mean to you?”

| Score | Definition | Example | Explanation of Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | No differentiation No Integration |

“I guess the first thing that comes to mind is being a citizen of the United States, being a citizen of a certain country.” | This answer states only one dimension/perspective of citizenship. |

| 2 | Emerging differentiation (e.g. they hint at the possibility of more but default to their first point without fully developing a second point) No Integration |

“It means that you’re an engaged part of society, whether that’s at the local or bigger level. But I think it varies from person to person what that engagement means.” | Stating that citizenship varies from person to person suggests that there may be more than one dimension/perspective, but an additional dimension is not explicitly stated. |

| 3 | Differentiation No Integration |

“I think to me being a citizen not only means kind of having an identity in a country or nationality or country you associate yourself with, but also being actively engaged in the political process and taking advantage of the rights that are given to you through the social compact.” | Here we see two dimensions/perspectives (identity and active engagement) which are differentiated from one another. |

| 4 | Differentiation and Emerging integration (e.g. there might have a superordinate statement that ties two differentiated concepts together, or there might be recognition of tensions or tradeoffs between the two concepts they have identified) | “Well I think to be a citizen you need to be an active participant in the process of choosing the leaders that are going to represent you. You know, whether that’s voting or whether that’s getting involved in various political action committees or just making your voice heard in some way or another. Because, then, if you don’t you don’t really have any chance to, or any reason to be able to complain legitimately when things don’t go your way. So for me, the biggest part is just being an active participant in the governing process.” | The first sentence serves as a superordinate statement, which is an emerging integration of the different dimensions/perspectives (voting and involvement). |

| 5 | Differentiation and Integration | “I think it first of all implies a connection to, a particular national identity. I’m a dual citizen of two countries, but I could say that I’m much more of a citizen of one particular country—my additional citizenship is New Zealand because my Dad is a New Zealander. But I’ve only traveled there a couple of times and I was born in the United States and raised here and live here even though I’ve spent a couple years abroad. And so while I’m technically a citizen of both countries, I think citizenship implies a lot more than just the legal connotation. Because I’m certainly more of a citizen of the United States and that I vote here. I reside here, of course. And I follow its politics and contribute to my particular community in the United States, which happens to be the Nation’s capital—D.C. So I think that’s my personal understanding of citizenship.” | This answer shows the different dimensions/perspectives of the citizenship: legal connotations, voting, and involvement. Additionally, these different perspectives are integrated into an overall understanding or definition of what citizenship means. |

Analyses

To determine differences between DFs and CCs on integrative complexity scores, we averaged each participant’s scores for the two questions on citizenship, and independent samples t-tests were used to test statistical differences. These results, reported in Table 2, show that DFs demonstrated significantly higher integrative complexity scores than did CCs (t(38) = 2.21, p < 0.05).

Integrative Complexity in Thinking About Citizenship Among Democracy Fellows and the Class Cohort.

| Group | t | df | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democracy Fellows M (SD) | Class Cohort M (SD) | |||

| Integrative Complexity | 3.43 (0.71) | 2.90 (0.79) | 2.21* | 38 |

Note: * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.001. M = Mean. SD = Standard Deviation.

We also examined differences between DFs and CCs for Political Science majors and non-Political Science majors. This breakdown of majors was done because of the unique emphasis on politics in political science majors, and because political science was the major for seven of the alumni in each group. As seen in Table 3, differences between DFs and CCs held only among those who did not major in Political Science. Among participants who did not major in Political Science, those who were in the Democracy Fellows program displayed more complex thinking about the definitions and responsibilities of citizenship than did those who did not participate in the DF program (t(24) = 2.68, p < 0.01). Among participants who majored in Political Science, participation in the DF program had no statistically significant effect on their integrative complexity scores (t(12) = –0.24, p > 0.05).

Integrative Complexity in Thinking About Citizenship Among Non-Political Science Majors in the Democracy Fellows and in the Class Cohort.

| Group | t | df | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democracy Fellows M (SD) | Class Cohort M (SD) | |||

| Non-Political Science Majors | 3.54 (0.72) | 2.69 (0.88) | 2.68** | 24 |

| Political Science Majors | 3.21 (0.70) | 3.29 (0.39) | –0.236 | 12 |

Note: * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.001. M = Mean. SD = Standard Deviation.

Qualitative Themes

Content analysis of the two citizenship questions revealed that our former students held three major conceptions of citizenship that we labeled Legal, Cultural/Identity, and Participatory. Our findings with respect to the use of these themes by DFs and CCs offer some further support for the differences in complexity of thought among our participants.

Legal citizenship conceptions were the most narrowly defined, and, as the name implies, focused on the legal requirement of citizenship. Thus, citizenship accrued to an individual due to being born in a particular place, or becoming naturalized, or was defined as obeying the law or meeting legal obligations. For example:

‘I guess just paying my taxes. And abide by the law.’

‘…Being documented in the United States.’

Cultural/Identity conceptions focused on citizenship as identification with a culture, a place, or a set of values—and experiencing a sense of belonging because of this identification. Answers coded as cultural/identity were characterized by talk of being part of a larger community or nation, and recognition that cultures and values vary from place to place. Example statements coded under this category included:

‘I think to me being a citizen … means kind of having an identity in a country or nationality or country you associate yourself with.’

‘Simply enough, I think a citizen is someone that is …, a part of the fabric of a country.’

‘Usually, citizenship is entailed when you are born there, but there are certainly cases where you can apply to be a citizen of a country and I guess if you want to take on the values of said country, then you can become a citizen.’

Participatory conceptions of citizenship focused on taking action, including voting, running for office, staying informed, volunteering, helping others, joining the armed services, or being part of community groups. For example, responses coded as Participatory reflected such things as:

‘I think citizens should be active participants in their community. And that means at the minimum—voting. But I’ve always felt like civic engagement is important, volunteerism, helping out where you can, when you can is a part of being a good citizen.’

‘To be a citizen is to be an active member of the social contract. I guess I’ve become more and more of the attitude that we are all in this together. Right or wrong, good or bad but we owe it to each other to be active participants in that, be it in a conversation setting or simply by voting.’

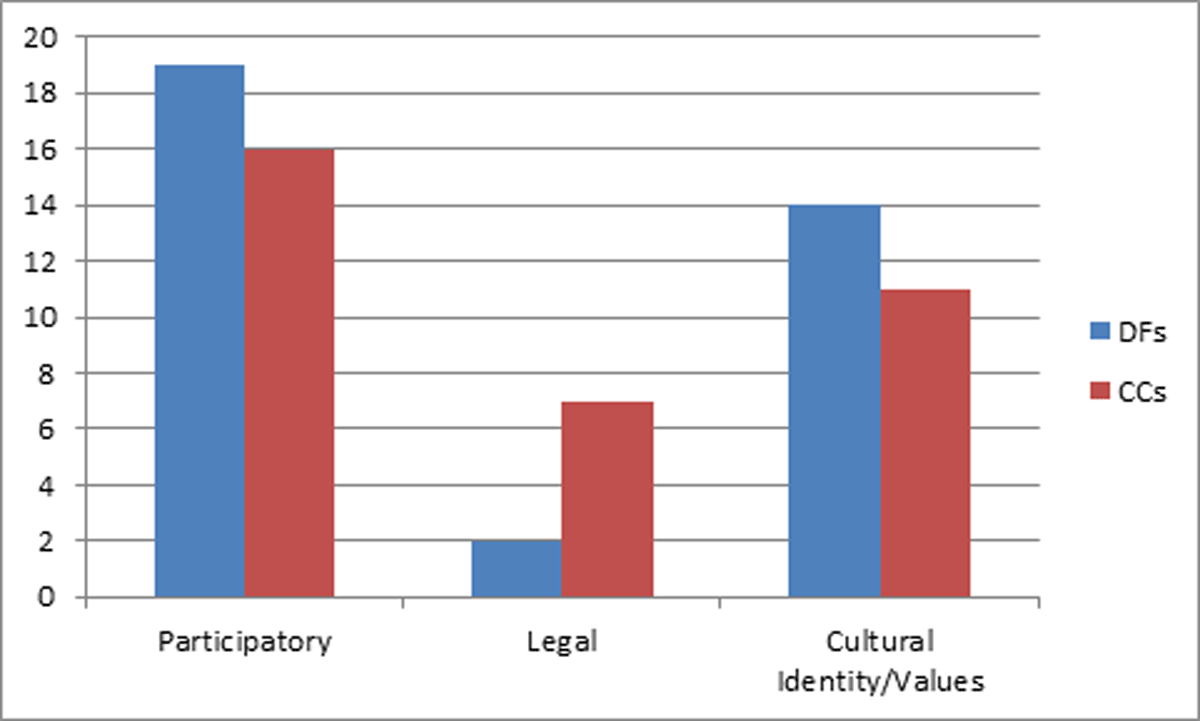

Figure 1 illustrates some differences between the DFs and CCs in terms of conceptions of citizenship. Although a majority in each group identified both participatory and cultural/identity aspects of citizenship, DFs were somewhat more likely than CCs to identify both as important. Nineteen of the 20 DFs emphasized participatory aspects and 14 of the DFs also emphasized cultural/identity aspects. In the CC group, 16 of 20 discussed participatory aspects and 11 of the 20 cultural/identity. A little over one-third of CCs (n = 7), on the other hand, focused on legal definitions while only one-tenth of DFs (n = 2) did.

DFs who did give legal definitions of citizenship also mentioned participatory aspects of citizenship, while most of the CCs with legal definitions mentioned only the legal aspect of citizenship. For example, here is the statement of a DF that was coded both Legal and Participatory:

‘I would say that obeying the laws of a country, so as a citizen of a country you can’t go around and violate established laws and rules and regulations established to keep everybody safe and so that everyone can live together as a citizen in that country. I would say also your job as a citizen, I think, is to contribute and to be productive as part of society, so I mean there are some people who choose to be free riders and don’t give anything back, but I think that’s one of the reasons why we have the tax system—so that you can also contribute to keep the country sustaining.’

In contrast, here is the statement of a CC coded only Legal:

‘I guess, we’re born in this country and so basically that makes us a citizen of the country. And so you have basic rights of the citizens that live here to vote, to be able to have, I guess, the rights guaranteed by the Constitution.’

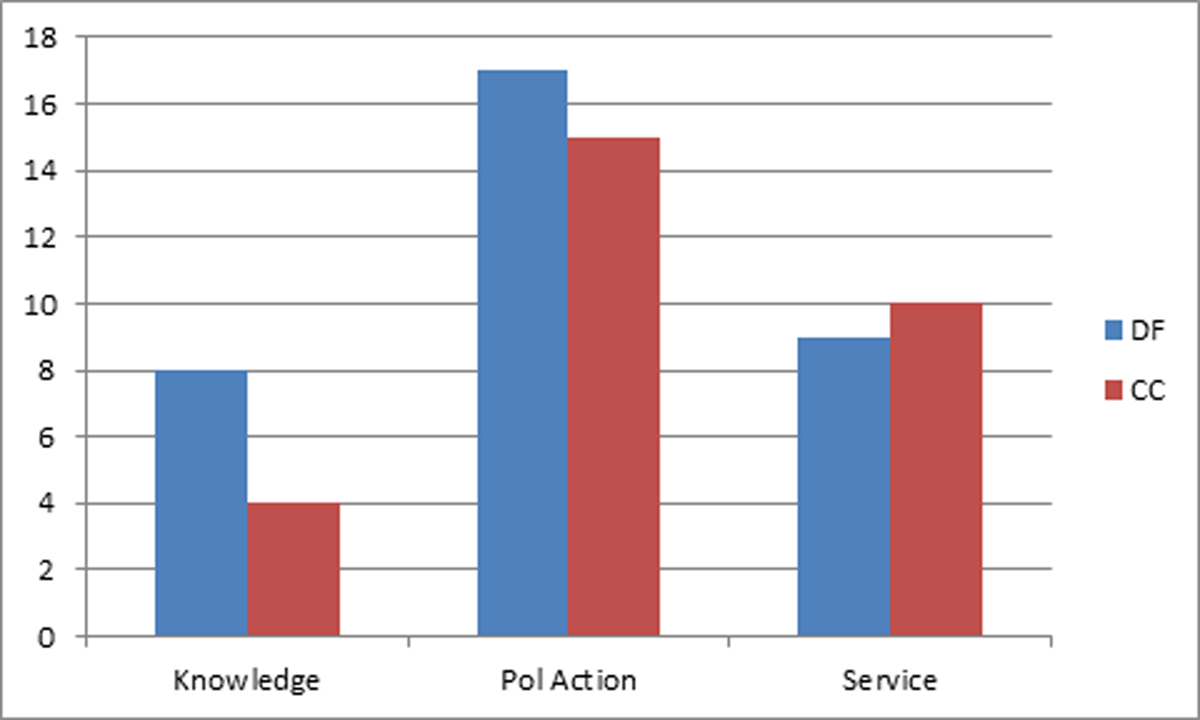

The groups also showed some differences in their descriptions of the responsibilities of citizenship (see Figure 2). Although both groups emphasized community service as a responsibility, DFs were twice as likely as CCs to emphasize the importance of staying informed or being knowledgeable about what is going on in politics as a responsibility of citizenship. DFs also often associated knowledge with participation. ‘I think that … probably the biggest obligation people have,’ said one DF, ‘is they need to be as informed as they are involved. Which means I think people shouldn’t be voting because they’ve been told to vote a certain way. They should be voting because they’ve thought about it and have like read and all of that sort of thing.’ Another said, ‘I think, citizenship… requires active participation and knowledge on the part of the participants of the issues that are impacting the citizens and active engagement as well as desire to understand what the needs and requirements are of that community.’

DFs were slightly more likely than CCs to name specific political actions that should be part of citizenship although in both groups a substantial majority named such acts (17 DFs, 15 CCs). It was noticeable, though, that DFs were more likely to weave their talk about participation in politics with themes about being knowledgeable and engaging with others:

‘I think fundamental to that is participating in the electoral process through voting. But I think that it also involves engaging other citizens and productive discourse in conversation to try to better understand issues at hand so that you can make more informed decisions. So it’s not just casting votes, it’s also informing yourself, helping other people to better understand the issues at hand, not necessarily your opinion of it, but just engage everybody in the process so that everybody can be more informed and the outcomes can also be better; more beneficial to everybody.’

‘From voting in yearly elections to I think even being aware of what’s going on in your community or at a national or state level. Some awareness of the issues. You know, I don’t think necessarily you have to be out protesting in the streets all the time or giving money to a political campaign or issue advocacy or something like that. I think it can mean a lot of different things. So, I think in general it’s engagement with your community on issues that matter and somehow engagement in the political process, I think, which is voting.’

The findings within the qualitative data support our thesis in two important ways. Not only do we find that the students who experienced the deliberation treatment ten years earlier consistently score at the higher reaches of the integrative complexity model, they also are more varied in their descriptions of what makes a citizen and what responsibilities that designation requires. For example, although most respondents recognize voting as essential to citizenship, DF’s responses suggest a higher likelihood of a more expansive civic literacy that includes being knowledgeable about issues and engaging with fellow citizens to solve problems. Despite one category, service, in which the CCs slightly outpace the DFs, the cohort group seemed to have more trouble imagining the broad and nuanced terrain of citizenship available to them that their DF counterparts identified.

Survey Data: Communication about Politics

Because we had a prediction about directionality (i.e. that DFs would score higher than CCs), one-tailed t-tests were used to compare means on the Communication about Politics scale. Results indicated that DFs (M = 3.98, SD = 0.91) scored significantly higher than the CCs (M = 3.53, SD = 0.79) on communication about politics, including with those whose opinions differed from their own (t(38) = 1.67, p < 0.05).

Discussion

Motivated by concerns about a ‘crisis in democracy’ that includes declines in willingness to engage in discussions, especially civil discussions, across difference (Iyengar & Westwood 2015; Klein 2020; Schaeffer 2020) as well as declines in complex thinking about community problems (Dryzek et al. 2019), the current study examined whether sustained experience in deliberation during college might contribute to more complex thinking about citizenship and a greater willingness to communicate about politics with those who hold different perspectives even ten years after college graduation. There were indications of such effects at the point of college graduation (Harriger & McMillan 2007). In this study, we examined whether there was evidence that such effects could be sustained over a longer period of emerging and young adulthood.

Our findings are consistent with the possibility that extensive deliberative experiences during emerging adulthood can contribute to more complex thinking about citizenship and a greater willingness to engage across differences that is sustained into young adulthood. Democracy Fellows, who had engaged in extensive deliberative experiences during college, spoke of citizenship and its responsibilities in more cognitively complex ways than did members of the class cohort, if they had not majored in political science. Political science majors’ education very likely addressed complexities of citizenship in a way that was redundant with the deliberation experience. However, for emerging adults not immersed in a political science curriculum, four years of exposure to discussion of citizenship and deliberation might have promoted greater complexity in their understanding of citizenship and its responsibilities a full decade later, beyond the general effects of a shared liberal arts education at the same small private liberal arts university.

This possibility is reinforced by the findings from the content analysis of the interviews. The Democracy Fellows displayed more complex and multifaceted notions of citizenship. For example, they were more likely to describe both participatory and legal aspects, and less likely to cite only legal aspects of citizenship. Furthermore, survey results indicated that DFs had a greater interest in and willingness to engage with people across political differences than did the cohort control participants.

The differences found in the current alumni study are similar to those detected at the point of college graduation, but the fact that they seem to persist ten years after the conclusion of the deliberative experience, when these young adults had made significant family and career transitions, is consistent with the prediction that emerging adulthood can be an important period for honing longer-lasting civic skills (Erikson 1968; McLean & Syed 2016). Although we cannot rule out that selection bias contributes to these differences, we argue that selection bias is unlikely to have played a large role. Recruitment of new students into the Democracy Fellows program, and of participants into the alumni study, employed strategies aimed to minimize selection bias, including the matching of DFs and CCs in the alumni study based on demographic characteristics and college major. DFs and CCs were asked the same questions, and DFs were interviewed by research staff who had not been involved in the DF program.

The findings are also consistent with theory and prior evidence, including research showing the benefits of experience in deliberation and discussion of policy and political issues on complexity of thinking and civic engagement more generally (e.g. Flanagan et al., 2014; Marzana et al. 2012; Tadmor & Tetlock 2006). Growing scholarship in both developmental and political psychology points to the possibility that providing emerging adults education about the value of deliberation along with sustained engagement in respectful dialogue that involves examining values and biases, listening to others’ experiences and viewpoints, and devising solutions that take into account diverse viewpoints has the potential to contribute to civic aspects of identity formation that are so critical at this time of life (McLean & Syed 2015). Subsequently, civic skills and inclinations such as the ability to recognize, differentiate, and integrate diverse perspectives; to think in complex ways about social and political issues; or the ability and willingness to communicate across differences, have the potential to increase civic engagement (Crocetti et al. 2014), and to help reduce polarization and promote more effective problem-solving in communities (Boyd-MacMillan et al. 2016; Colombo 2018).

In their study showing that calling college students’ attention to differentiation and integration can result in more complex thinking, Hunsberger et al. (1992) argue that ‘if the aim of education is seen broadly as improving the quality of our thinking, then one must consider the possibility that specific interventions designed to increase complexity of thought processes in context are both feasible and desirable’ (p. 113). We believe our findings on the impact of deliberation support this conclusion in the area of civic education. The current findings bolster the conclusion of Samuelsson and Boyum’s (2015) extensive review of education for deliberative democracy, which pointed to ‘overarching agreement’ that individuals can and should learn the skills and values of deliberative democracy by actually participating in deliberations. Learning to deliberate, through a process where emerging adults are prompted to think about different points of view and the tensions and tradeoffs in policy debate, appears to have the potential for long-term impact on how they view their rights and responsibilities as citizens. Their recognition of the complexity of their role in communities and the political system and/or their practice in deliberation encounters might each have a role in enhancing long-term willingness to engage with others about political issues, even others with whom they disagree. Recent research pointing to the importance of ‘feeling heard’ in civic empowerment and engagement (Wray-Lake & Abrams 2020) offers yet another possible reason for deliberation’s benefits. Perhaps it is through being heard, as well as hearing others, that participants in deliberation become more comfortable with conversation around challenging issues.

It seems important to acknowledge that the deliberative experience of the DFs included more than just the practice of deliberation; it was preceded by an extensive study in the theory and art of deliberation, and, in particular, why it is an appropriate tool of democratic citizenship Prior to their very first practice, DFs studied the struggle of the founders as they sought to determine the role of the people, the foundation and tenets of deliberative theory, the push-back from critics who recognized the theory’s flaws, and group communication theory, which explained and fine-tuned the ability of participants to ‘listen actively’ and to respond clearly and thoughtfully. Thus, any long-term impact might have been contingent on the depth of learning about deliberation as well as the breadth of practice.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research

A major strength of our study is that it is a rare longitudinal investigation of the long-term impact of intensive deliberative experience during emerging adulthood. The fact that the differences found in the alumni study are similar to those detected at college graduation (Harriger & McMillan 2007), despite ten intervening years and many crucial life experiences, offers some evidence that education in deliberative ideas and practices have staying power. Additional strengths of the study include the collection and analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data, using measures that had been validated in previous research. Importantly, we sought formal training in and used an objective methodology to quantify integrative complexity that has been used broadly in the literature on integrative complexity.

Another set of both strengths and limitations emerges from the recruitment and characteristics of participants in our study. A strength is that extensive efforts were made, both in recruiting participants into the ‘intervention’ program and in recruiting the cohort control group of young adults ten years later, to minimize the impact of selection variables that could influence outcomes of interest. Nonetheless, this was not an experimental study and selection effects cannot be entirely ruled out. It is possible that factors other than those we could control (e.g. demographic factors, choice of college major) contribute to differences between our group instead of the deliberative experiences participants had during college.

The deliberative experience for DFs was unusual in its intensity and length, and in having instructed participants as to why they are deliberating as well as engaging them in repeated practice of deliberation (also see Shaffer 2016). The breadth and depth of the program might very well account for any long-term effects. One limitation introduced by the intensity of the program was that a relatively small cadre of students were able to participate, and, although there was excellent retention in the DF program over the four college years, we were not able to reach all of them ten years later. Thus, our alumni sample is small, restricted to twenty program participants and twenty control cohort members. Given the small sample, the shared liberal arts college education of the two groups, and the number of years that had passed, it is notable that we found any significant differences consistent with our hypotheses, but not surprising that the differences that emerged were sometimes small in magnitude.

Mirroring the demographic makeup of students at the university in which the study was conducted, the majority of participants were White. Therefore, although our results are suggestive of the potential for intensive deliberative experience to shape the thinking and political communication of emerging adults in a positive manner, additional research using larger and more diverse samples is important, to see if the results replicate and generalize to other populations.

Elucidating the processes through which deliberative experience promotes integrative complexity about citizenship or a willingness to communicate about politics is a ripe area for future research. Kuyper (2018) argues that at the micro-level of investigation where ‘individual preferences, knowledge, and civic desires can be driven’, it is unclear what aspect of deliberation is ‘doing the causal work’ (p. 7). Our study does not answer this question, but raises the possibility that the effects of deliberative experience, especially longer-term effects, might be improved by learning not only the ‘how-tos’ but also the ‘whys’ of deliberative practice. Additional longitudinal research investigating different elements of the educational experience is important if educators are going to be able to confidently identify the critical elements of deliberative education. Extending research on other potential outcomes of the deliberative experience is also worth considering. For example, do the varied definitions of citizenship articulated by the DFs and CCs correlate with larger conceptions of democracy, such as liberal, participatory, and deliberative concepts, and if so, how might those correlations inform civic education going forward?

Despite substantial emerging evidence supporting the impact of deliberation experiences on the development of cognitive complexity in individuals, there also remains much to study in terms of this experience on groups. Related to the overarching need, mentioned above, to elucidate particular parts of the deliberative experience that are most important to cognitive development, it would be worthwhile to investigate what role language plays in the cognitive growth of the group; does it matter how critical issues in the discussion are characterized linguistically, by the moderator or by participants? Are there special strategies that a moderator might employ that would encourage participants to think more deeply, creatively, or expansively?

Finally, our study highlights the value of integrative complexity scoring as a methodology for assessing the impact of deliberative training and other civic engagement interventions designed to encourage young people to engage with others in a pluralistic society. It would also be of interest to assess complexity at the group level, drawing on emerging discussions of how a group complexity score might be measured (see Niemeyer 2019 for a discussion of intersubjective reasoning). It would be helpful to gather data on whether groups populated by participants with higher integrative complexity scores are more politically active, make better decisions, or implement more solutions that have broader community acceptance and impact. Overall, our study adds to existing theory and research that in the highly conflictual and polarized climate of American politics, deliberative training during emerging adulthood offers some hope for educating citizens to be skeptical of absolutist claims, open to new evidence and ideas, and willing to engage across difference. Although further research is necessary to expand understanding of the mechanisms by which, and the contexts in which, deliberation experience enhances civic development, the ‘crisis of democracy’ we face suggests that we should take steps to prioritize deliberative experience in education in ways that can promote greater understanding and more civil participation.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

1 Baker-Brown, G., Ballard, E. J., Bluck, S., deVries, B., Suedfeld, P., & Tetlock, P. E. (1990). Scoring manual for integrative and conceptual complexity. Vancouver, Canada: University of British Columbia.

2 Ballard, P. J., Caccavale, L., & Buchanan, C. M. (2015). Civic orientation in cultures of privilege: What role do schools play? Youth & Society, 47(1), 70–94. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X14538464

3 Boyd-MacMillan, E. M., Campbell, C. & Furey, A. (2016). An IC intervention for post-conflict Northern Ireland secondary schools. Journal of Strategic Security, 9(4), 111–124. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.9.4.1558

4 Colombo, C. (2018). Hearing the other side? Debiasing political opinions in the case of the Scottish independence referendum. Political Studies, 66(1), 23–42. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0032321717723486

5 Conway, L. G., Conway, K. R., Gornick, L. J., & Houck, S. C. (2014). Automated integrative complexity. Journal of Political Psychology, 35(5), 607–624. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12021

6 Cramer, K. J., & Toff, B. (2017). The fact of experience: Rethinking political knowledge and civic competence. Perspectives on Politics, 15(3), 754–770. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592717000949

7 Crocetti, E., Erentaitė, R., & Žukauskienė, R. (2014). Identity styles, positive youth development, and civic engagement in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(11), 1818–1828. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0100-4

8 Dedrick, J., Grattan, L., & Dienstfrey, H. (Eds.) (2008). Deliberation and the work of higher education: Innovations for the classroom, the campus, and the community. Dayton, OH: Kettering Foundation Press.

9 Dryzek, J. S., Bachtiger, A., Chambers, S., Cohen, J., Druckman, J. N., & Felicetti, A., et al. (2019). The crisis of democracy and the science of deliberation. Science, 363(6432), 1144–1146. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw2694

10 Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

11 Flanagan, C. A. (2004). Volunteerism, leadership, political socialization, and civic engagement. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology., 2nd ed. (2004-12826-022; pp. 721–745). John Wiley & Sons Inc. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/9780471726746.ch23

12 Flanagan, C. A., Kim, T., Pykett, A., Finlay, A., Gallay, E. E., & Pancer, M. (2014). Adolescents’ theories about economic inequality: Why are some people poor while others are rich? Developmental Psychology, 50(11), 2512–2525. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1037/a0037934

13 Flanagan, C. A., Syvertsen, A. K., & Stout, M. D. (2007). Civic measurement models: Tapping adolescents’ civic engagement. Circle (The Center for Information and research on Civic Learning and Engagement) Working Paper 55.

14 Gastil, J. (2008). Political communication and deliberation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4135/9781483329208

15 Gronlund, K., Setala, M., & Herne, K. (2010). Deliberation and civic virtues: lessons from a citizen deliberation experiment. European Political Science Review, 2(1), 95–117. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773909990245

16 Harriger, K. H., & McMillan, J. J. (2007). Speaking of politics: Preparing college students for democratic citizenship through deliberative dialogue. Dayton, OH: Kettering Foundation Press.

17 Hess, D. E. (2009). Controversy in the classroom: The democratic power of discussion. New York: Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9780203878880

18 Ho, D., Imai, K., King, G., & Stuart, E. A. (2007). Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference, Political Analysis, 15, 199–236. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpl013

19 Hunsberger, B., Lea, J., Pancer, M., Pratt, M., & McKenzie, B. (1992). Making life complicated: Prompting the use of integratively complex thinking. Journal of Personality, 60, 95–114. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00267.x

20 Iyengar, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and loathing across party lines: New evidence of group polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 690–707. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12152

21 Jacobs, L. R., Cook, F. L., & Delli Carpini, M. X. (2009). Talking together: Public deliberation and political participation in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226389899.001.0001

22 Jennstal, J. (2019). Deliberation and complexity of thinking. Using the integrated complexity scale to assess the deliberative quality of mini publics. Swiss Political Science Review, 25(1), 64–83. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12343

23 Kahne, J., Middaugh, E., & Schutjer-Mance, K. (2005). California civic index [Monograph]. New York: Carnegie Corporation and Annenberg Foundation.

24 Klein, E. (2020). Why we’re polarized. New York: Avid Readers Press.

25 Kuyper, J. W. (2018). The instrumental value of deliberative democracy—Or, do we have good reasons to be deliberative democrats? Journal of Public Deliberation, 14(1), Article I. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.291

26 Landemore, H., & Mercier, H. (2012). Talking it out with others vs. deliberation within and the law of group polarization: Some implications of the argumentative theory of reasoning for deliberative democracy. Analise Social, 47(205), 910.

27 Marzana, D., Marta, E., & Pozzi, M. (2012). Young adults and civic behavior: The psychosocial variables determining it. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 40(1), 49–63. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2012.633067

28 McLean, K. C., & Syed, M. (2015). Personal, master, and alternative narratives: An integrative framework for understanding identity development in context. Human Development, 58(6), 318–349. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1159/000445817

29 Nabatchi, T. (2010a). Addressing the citizenship and democratic deficits: Exploring the potential of deliberative democracy for public administration. American Review of Public Administration, 40(4), 376–399. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0275074009356467

30 Nabatchi, T. (2010b). Deliberative democracy and citizenship: In search of the efficacy effect. Journal of Public Deliberation, 6(2): Article 8. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.109

31 Nabatchi, T., Gastil, J., Leighninger, M., & Weiksner, G. M. (2012). Democracy in motion: Evaluating the practice and impact of deliberative civic engagement. New York: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199899265.001.0001

32 National Issues Forum Institute (NIFI). (2002). Making choices together: The power of public deliberation. Dayton, OH: Kettering Foundation Press.

33 Niemeyer, S. (2011). The emancipatory effect of deliberation: Empirical lessons from mini-publics. Politics and Society, 39(1), 103–140. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0032329210395000

34 Niemeyer, S. (2019). Intersubjective reasoning in political deliberation: A theory and method for assessing deliberative transformation at small and large scale. Centre for Deliberative Democracy and Global Governance Working Paper Series No. 2019/4.

35 Neuman, W. R. (1981). Differentiation and integration in political thinking. American Journal of Sociology, 86, 1236–1268. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1086/227384

36 Pancer, S. M., Hunsberger, B., Pratt, M. W., & Alisat, S. (2000a). Cognitive complexity of expectations and adjustment to university in the first year. Journal of Adolescent Research, 15(1), 38–57. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0743558400151003

37 Pancer, S. M., Pratt, M., Hunsberger, B., & Gallant, M. (2000b). Thinking ahead: Complexity of expectations and the transition to parenthood. Journal of Personality, 68(2), 253–280. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00097

38 Samuelsson, M., & Boyum, S. (2015). Education for deliberative democracy: Mapping the field. Utbildning och Demokrati, 24(1),75–94. DOI: http://doi.org/10.48059/uod.v24i1.1031

39 Schaeffer, K. (2020). Far more Americans see ‘very strong’ partisan conflicts now than in the last two presidential election years. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/04/far-more-americans-see-very-strong-partisan-conflicts-now-than-in-the-last-two-presidential-election-years/

40 Shaffer, T. J. (2016). Teaching deliberative democracy deliberatively. Journal of Public Affairs, 5(2). 93–113. DOI: http://doi.org/10.21768/ejopa.v5i2.4

41 Suedfeld, P. (2010). The cognitive processing of politics and politicians: Archival studies of conceptual and integrative complexity. Journal of Personality, 78, 1669–1702. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00666.x

42 Suedfeld, P., Bluck, S., Loewen, L. J., & Elkins, D. J. (1994). Sociopolitical values and integrative complexity of members of student political groups. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 26(1), 121–141. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1037/0008-400X.26.1.121

43 Tadmor, C. T., & Tetlock, P. E. (2006). Biculturalism: A model of the effects of second-culture exposure on acculturation and integrative complexity. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37, 173–190. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0022022105284495

44 Tetlock, P. E. (1986). A value pluralism model of ideological reasoning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 819–827. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.50.4.819

45 Tetlock, P. E. (1992). The impact of accountability on judgment and choice: Toward a social contingency model. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 331–376. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60287-7

46 The National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement. (2012). A crucible moment: College learning and democracy’s future. Washington, DC: AAC&U.

47 Wray-Lake, L., & Abrams, L. S. (2020). Pathways to civic engagement among urban youth of color. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 85(2), 7–154. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/mono.12415

48 Wray-Lake, L., & Flanagan, C. A. (2012). Parenting practices and the development of adolescents’ social trust. Journal of Adolescence, 35(3), 549–560. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.09.006