Introduction

Deliberative mini-publics (DMPs)—defined as deliberative forums of citizens where citizens are selected randomly from the wider population to gather and deliberate on a defined set of issues, and then formulate policy recommendations (Curato et al. 2021)—are spreading across democracies (OECD 2022). Public authorities have introduced them across various levels of government to deliberate and formulate policy recommendations across a wide range of topics (Paulis et al. 2020). In a few countries like Ireland or Belgium, mini-publics have even been institutionalized as a recurrent feature of policymaking (Macq & Jacquet 2023; Reuchamps, Vrydagh & Welp 2023). One hope is that they could generate public legitimacy and policy acceptance more easily than representative institutions, which suffer from a lack of trust among citizens (Muradova & Suiter 2022). Such a positive effect on policy acceptance is getting even more crucial as contemporary societies face tough and complex challenges (like climate change), which require important further decisions to be made but may be difficult to accept. The argument is that opening the decision-making process to ordinary citizens will make people identify more with those making the decisions and therefore be more supportive of these decisions (Barber 1984; Dryzek et al. 2019; Pateman 1970).

However, comprehensive empirical evidence as to whether mini-publics can indeed boost the legitimacy of policy decisions is still lacking. So far, a few studies have shown that the broader public’s evaluation of such processes is more related to the content of the policy recommendations formulated than to the deliberative procedures per se (Christensen, Himmelroos & Setälä 2020; Esaiasson et al. 2019). Coming back to the classical typology of what generates political legitimacy, it appears that citizens are more affected by output considerations (linked to policy content) than by input (linked to who decides) or throughput (linked to the decision-making process and procedures) factors (Bekkers & Edwards 2007; Caluwaerts & Reuchamps 2015). Nevertheless, even if the content of policies particularly matters to accept them, a few scholars have highlighted that mini-publics may also boost policy legitimacy because they include citizens in policymaking (Christensen 2020; Esaiasson, Gilljam & Persson 2012; Goldberg 2021; Ingham & Levin 2018; Pow 2021; Werner & Marien 2022).

Building on those studies, our goal in this article is to look specifically at one dimension of mini-publics, which is their composition: that is, who participates, who are those citizens who have been randomly selected and have accepted to join the deliberative process. This goal directly connects to one of the core defining features of mini-publics and the sortition mechanism used to recruit the participants (Fishkin 2009; Warren & Gastil 2015). Sortition aims to guarantee that it mirrors the broader population and the different groups composing it. It thereby contributes to the legitimacy of such a process, as it ensures that citizens will find participants who ‘are like them’, with whom they can identify through a shared background and experience (Pow, van Dijk & Marien 2020). Yet, some empirical observations of mini-publics lead to challenging those assumptions. First, many citizens in the broader public are simply unaware of what mini-publics are and that they are organized in the country. They thus do not know anything about the composition. Second, although most mini-publics reach some diversity and representativeness in certain aspects, they remain heavily biased toward others. In particular, citizens who accept to participate are more politically engaged than average and hold firmer views on the issue that is debated (Flanigan et al. 2021; Jacquet 2017). It implies that more critical or minority opinions are less considered when shaping decisions through sortitioned bodies. Therefore, how would non-participating citizens react once they learn about who the selected participants are and how (well) representative they are of the population? Does the public care about the composition of a mini-public for accepting the outcomes? We want to examine whether getting information about who mini-public participants are and how representative they are of the broader population would affect the public legitimacy of the policy recommendations formulated by the mini-public.

To address these questions and objectives, we ran a survey experiment in parallel to a national-level Climate Citizens’ Assembly (Klima Biergerrot – KBR) commissioned by the national government of Luxembourg in 2022. Our experimental design exposes respondents to six vignettes providing information about the actual representation of various socio-economic and political groups among KBR participants. Our findings convey two messages. First, there is no universal effect of learning details about the composition of a mini-public. Citizens’ willingness to accept the policy recommendations is not influenced very much by learning about who the participants are and the fair or unfair representation of some specific groups. Yet second, we show that DMP composition can matter for individuals who are in a situation of cognitive dissonance. For example, when ‘participatory skeptics’ learn about the fair representation of (their in-) groups in the DMP, their policy acceptance increases. In contrast, unfair representation does not affect them, as it confirms their negative impression. Overall, we believe our study demonstrates that it would be very relevant to conduct further research on a wider set of elements in the composition of mini-publics, as it may be relevant for citizens outside the citizens’ assembly. Such studies would consolidate our knowledge of the importance of mini-public composition for non-participants, and it would help professionals of deliberative assemblies to improve their recruitment strategies for a diversity of participants if they hope that mini-publics can contribute to generating policy acceptance and public legitimacy.

Theory

Deliberative mini-publics: more representative and thus responsive?

Over the last decades, established democracies implemented different mechanisms aimed at increasing the participation of citizens in policymaking (Geissel & Newton 2012). DMPs are among those instruments that have gained prominence (Paulis et al. 2020). These bodies are made of citizens selected randomly to mirror the broader public and who deliberate together to formulate policy recommendations for representative institutions (Curato et al. 2021). According to deliberative theory, such deliberative instruments are expected to boost the legitimacy of public decisions for two main reasons (Fishkin 2009). First, because of their deliberative nature, they would generate better informed and more reasoned decisions. Second, sortition leads to a diverse composition, brings more equality into policymaking, and ensures that the interests of all parties are fairly represented (Delannoi & Dowlen 2016).

A core feature of DMPs lies, therefore, in the way they are composed. Participants are recruited via civic lottery, combined with some stratification with quotas defined on a series of sociodemographic traits (age, gender, place of residence, education), and, though more rarely, on some social or political attributes related to the issue at stake (Paulis et al. 2020). The goal is twofold. First, it aims at building a mini-public that mirrors the ‘maxi-public’ (Smith 2009). This is linked to the logic of ‘descriptive representation,’ according to which fair representation is ensured by the presence in institutions of individuals who reflect the characteristics of the different groups that co-exist in society (Lemi 2022; Mansbridge 1999; Pitkin 1967). Second, the use of random selection is associated with the willingness to offer a better representation of groups often absent or under-represented in elected institutions (Curato et al. 2021). Such a composition would have two effects on how DMPs are perceived by the wider public. First, descriptive representation allows non-participating citizens to identify with the deliberative process and trust the recommendations that are made by the participants who are people like them (Pow, van Dijk & Marien 2020). Second, the guaranteed representation of traditionally under-represented groups would boost the perceived fairness of the process (Farrell & Stone 2020; Gąsiorowska 2023).

Representativeness in mini-publics: a smoked mirror?

However, empirical research on the actual profiles of mini-public participants has shown that the principle of descriptive representation is not as easy to implement as it may seem. On the one hand, only a small part of the citizens randomly selected accept to participate, and self-selection is biased socially (Jacquet 2017). Confirming a wealth of research on political participation (Armingeon & Schädel 2015), those who accept to join tend to come from more affluent and privileged social groups, and less often from minorities and disengaged groups (Malkopoulou 2015). To counter these problems, practitioners rely on two strategies: they use quotas and stratification techniques in their sampling of the population (to ensure perfect descriptive representation), or they over-represent some minority groups in the final group of mini-public participants (taking deliberately some distances from the pure principle of descriptive representation for the sake of positive discrimination). Yet, those strategies do not fully compensate for inequalities in participation in mini-publics. First, DMP organizers can only stratify among those who have replied positively to the first invitation letter. Some groups have already dropped out before stratification, making perfect representation hard to reach on some traits like education (Visser, de Koster & van der Waal 2021). Second, stratification is in most cases only based on a few sociodemographic traits (like age, gender, occupation, education, and place of residence). Other traits, and especially political attitudes, are rarely considered. There are a few exceptions, but they remain rare (Paulis et al. 2020). Consequently, participants are often more interested in politics, more efficacious, or already engaged in other forms of participation (Fourniau 2019). This bias is even observed among potential mini-public participants from less privileged groups (Talukder & Pilet 2021).

There is another important obstacle to the expectation that policy recommendations from deliberative mini-publics could contribute to policy acceptance. Despite their increasing use and visibility, there remains a huge deficit of familiarity with these institutions among the population (Jacquet, Niessen & Reuchamps 2020), which can be problematic for their legitimacy. How could people identify with the process and its outcomes if they do not know anything about it?

To counter this familiarity problem, extant research has mostly relied upon experiments in which respondents were exposed to explicit vignettes about fictional mini-publics (see Goldberg 2021; Goldberg & Bächtiger 2022). Under such conditions of good information, it appears that people evaluate more positively public decisions when they know they have been reached through deliberative processes (Esaiasson et al. 2012/2019; Ingham & Levin 2018; Werner & Marien 2022). The strongest factor in how citizens evaluate mini-publics is how favorable they perceive the content of their policy recommendations (Arnesen 2017; Esaiasson et al. 2019; Pilet et al. 2021). But how exactly the deliberative process is organized—its procedures, its participants, the quality of the deliberation—also matters when citizens judge mini-publics (Goldberg 2021; Goldberg & Bachtiger 2022; Jacobs & Kaufmann 2021; Pow, van Dijk & Marien 2020). The inclusive and diverse composition of mini-publics, derived from random selection, is positively evaluated. The idea that mini-publics are representative of society at-large stands in contrast with representative institutions that overall tend to be rather different from the wider public in terms of sociodemographic attributes (Bartels 2008; Lefkofridi, Giger & Kissau 2012; Rosset 2016). This comparison between mini-publics and representative institutions turns in favor of the former (Werner & Marien 2022).

However, those latter studies suffer from two problems. First, they expose respondents to fictional mini-publics, maximizing the internal validity of the findings but reducing their external validity (Stoker 2010). Second, they provide very little information on who the mini-public participants are. Vignettes usually mention that the mini-public is constituted via sortition to ensure a fair representation of most groups in society, but they do not specify what the exact profiles of participants are (Esaiasson et al. 2019: Goldberg 2021; Ingham & Levin 2018). When they do, they would just say that mini-publics are representative of society at large on a few sociodemographic traits (Muradova & Suiter 2022; Pow 2021). And, as we have elaborated above, we know that the composition of mini-publics might remain skewed if we go beyond a few sociodemographic characteristics. In several countries that have organized mini-publics, skeptics have often pointed out the skewness of the participants’ recruitment and criticized these processes as dominated by activists and party supporters (Grandjean 2024; Rangoni, Bedock & Talukder 2023). Regarding Luxembourg’s climate assembly (KBR), this line of reasoning was developed by several press articles claiming that the process was suffering from a lack of representativeness and hence was selective, homogeneous, and not accessible to all citizens.1

Therefore, the question that we pose here and that we aim to address via a survey experiment building on a mini-public that was taking place is what would happen in terms of outcome acceptance if citizens received accurate information about the representation of certain groups, stressing eventually some problems of imperfect representation within the process?

Hypotheses

The main goal of the study is to examine how the composition of mini-publics influences non-participants’ willingness to accept the recommendations that will be formulated. We develop two series of hypotheses. On the one hand, the main effects’ hypotheses are expected to apply to all non-participants. In theory, learning about fair representation of a social group should trigger a positive stimulus and boost policy acceptance, whereas misrepresentation should have a negative impact. On the other hand, the second set of hypotheses does not assume the main effects to hold equally for all respondents but rather assumes some subgroup effects. First, building on studies in psychology about cognitive dissonance (Cooper 2019), we suggest that our vignettes will have an impact only if they contradict respondents’ pre-treatment opinions about the mini-public. Second, we expect also to observe differences between respondents depending on whether the vignette exposed them to information about the inclusion of citizens like them (in-group) or not like them (out-group).

Main effects’ hypotheses

Our first set of hypotheses builds upon earlier studies on procedural fairness as a factor affecting citizens’ evaluation of policy processes and the policy decisions that they generate. We expect that three dimensions of fair representation could be at play for all respondents: the fair representation of all groups (H1: descriptive representation), the fair representation of traditionally underrepresented groups (H2a: positive discrimination), and the limited presence groups traditionally overrepresented politically (H2b: positive discrimination).

Descriptive representation hypothesis (H1)

The first hypothesis postulates that respondents care about the overall fairness of the composition of the mini-public. They want all groups in society to have a place within the mini-public and therefore want it to perfectly mirror their weight within society at large. We know indeed that, along with procedural fairness, participatory equality is an important principle when citizens evaluate decision-making processes and their outcomes (Christensen et al. 2023; Jäske 2019). Besides, statistical representativeness is crucial to the legitimacy of deliberative polling techniques (Fishkin 2009), as it ensures that the nature of the deliberation within the mini-public replicates what would happen with a similar deliberation with the whole population. Within this logic, the statistical representativeness of a mini-public is expected to boost outcome acceptance because this information will trigger a positive stimulus that appeals to the value of equality and the belief that all citizens have an equal chance of influencing the political process (Brown 2006; Dryzek & Niemeyer 2008; Landemore 2013).

Hypothesis 1. Information about (a) the fair representation of any group will increase the respondents’ willingness to accept the policy recommendations of a mini-public, whereas (b) the unfair representation of any group will decrease it.

Positive discrimination hypothesis (H2)

It might be that respondents do care about fair representation within mini-public, but only of certain specific groups. Especially, respondents are expected to pay attention to the fair inclusion of citizens from less affluent groups, which are traditionally less represented within political institutions. Indeed, deliberative processes are often argued to provide better representation of these groups that are marginalized in society and representative institutions, like women, citizens with lower levels of education, or members of minorities (Ryan & Smith 2014; Setäla & Smith 2018). The idea here is thus that we should not be obsessed with mini-publics being perfectly statistically representative, but rather with their capacity to address socio-political inequalities and to compensate for the under-representation of certain groups in politics (Steel et al. 2020). However, as we have explained above, it is very hard for mini-public organizers to make sure that the most vulnerable groups are fairly represented among the participants, implying that they remain often under-represented in practice. Therefore, if respondents do care about the representation of less affluent groups, they should react negatively in terms of outcome acceptance when confronted with information about the low presence of most vulnerable groups within mini-publics.

Hypothesis 2a. Information about the under-representation of politically disengaged groups will decrease the respondents’ willingness to accept the policy recommendations of the mini-public.

The other facet of this story is that respondents could react negatively also when groups that are traditionally over-represented in political institutions are also over-represented within the mini-public. Indeed, past evaluations of deliberative processes have confirmed that highly citizens very interested in politics, skilled or holding firmer views on the topic are generally more present (Buzogany et al. 2022; Elstub et al. 2021; Paulis, Kies & Verhasselt 2024). We expect that learning about this sends a signal of domination and representation biases and suggests that lower profiles or critical opinions might be under-considered in the process. Hence, it should trigger a negative stimulus that will decrease the acceptance of the mini-public outcomes.

Hypothesis 2b. Information about the over-representation of groups that are politically engaged will decrease the respondents’ willingness to accept the policy recommendations of the mini-public.

Subgroup effects’ hypotheses

The first set of hypotheses was about the main effects that should apply to all respondents, irrespective of their own profiles and opinions. Yet, we also develop hypotheses postulating that not all respondents would be equally impacted by the information received about the composition of the mini-public. A first subgroup difference depends on respondents’ pre-treatment opinion about the mini-public. It builds on earlier studies on cognitive dissonance and how individuals update their attitudes when exposed to information that reinforces or contradicts their prior beliefs. The second emerges from the idea that citizens are more egotropic than sociotropic and are therefore more affected by information related to their in-group than to out-groups.

Cognitive dissonance hypothesis (H3)

In this study, we are, in fact, examining potential attitudinal change. We look at whether respondents are updating their willingness to accept policy recommendations from a mini-public when learning about the composition. Even though attitudes are rather stable over time, they can change when individuals are exposed to new information (Albarracin & Shavitt 2018). Social psychology research has widely emphasized that cognitive dissonance is a key driver of attitude change (Festinger 1957). Cognitive dissonance occurs when individuals are exposed to a new piece of information that contradicts their prior beliefs. It generates a situation of discomfort, which leads people to update their attitudes (Cooper 2019). By contrast, when individuals are exposed to information that is in line with prior beliefs, it comforts their opinions and does not trigger attitude change.

Translating it to our study, the effects of our vignettes are expected to be different depending on the respondents’ attitudes regarding mini-publics before the experimental manipulation. Our treatments present information about situations of fair and unfair representation within the mini-public (see Table 1). In the case of fair representation, we might expect that the vignette will mostly influence those respondents who had negative views on the mini-public before the experimental manipulation, as these ‘participatory skeptics’ will be in a situation of cognitive dissonance. In contrast, the ‘participatory enthusiasts’ with prior positive attitudes are not expected to change their minds about the mini-public based on information about their fair representation, because this just provides them a signal of confirmation of their prior positive opinion. What this subgroup should be more affected by is information about the unfair composition of the mini-public because this is precisely when they will be in a situation of cognitive dissonance, meaning that the new information challenges their initial positive stance regarding participatory processes.

Hypothesis 3. Information about (a) the fair composition of the mini-public will increase the willingness to accept the policy recommendations among the ‘participatory skeptics,’ whereas (b) the unfair composition will decrease it among the ‘participatory enthusiasts.’

Table 1: The experimental task.

| Introduction text about the mini-public | |||

| The government of Luxembourg has decided to organize a Citizens’ Assembly on Climate called the Klima-Biergerrot (KBR hereafter in the rest of the survey). It is bringing a group of 60 citizens (+ 40 substitutes) selected by lot, living, or working in Luxembourg. Meeting around 15 times, they are tasked with discussing Luxembourg’s current commitments as regards combating climate change, and with developing possible additional measures or proposals. At the end of this process, the KBR recommendations will be presented to the Luxembourg government. | |||

| Vignettes on mini-public composition | |||

| Sociodemographic traits: education and nationality | N | % | Message |

| V1: According to information provided by the organization of the KBR, 40% of the participants have reached a master’s degree, meaning that they spent 4 years or more at the university. According to population statistics provided by the OECD, 30% the Luxembourg population had a master’s degree on the 1st January 2022. | 331 | 14.7 | Unfair representation: over-representation of high educated |

| V2: According to information provided by the organization of the KBR, 36% of the participants have reached, at maximum, a degree of upper secondary education. According to population statistics provided by the OECD, 46% the Luxembourg population had, at maximum, a degree of upper secondary education on the 1st January 2022. | 348 | 15.5 | Unfair representation: under-representation of low educated |

| V3: According to information provided by the organization of the KBR, 53% of the participants are Luxembourg nationals who have only the Luxembourgish citizenship. According to population statistics provided by the national institute of statistics (Statec), the proportion of nationals in the Luxembourg population was 53% on the 1st of January 2022. | 299 | 13.3 | Fair representation: statistical representativeness of nationals (and non-nationals) |

| Political traits: interest in politics and satisfaction with incumbent government | |||

| V4: According to a study led by the University of Luxembourg, 43% of the participants find politics very interesting. Another survey led among a representative sample of the Luxembourg population indicates that 24% find politics very interesting. | 345 | 15.3 | Unfair representation: over-representation of highly interested in politics |

| V5: According to a study led by the University of Luxembourg, 80% of the participants are satisfied with the way the government of Xavier Bettel is running the country. Another survey led among a representative sample of the Luxembourg population indicates that 60% is content with Bettel’s government. | 291 | 12.9 | Unfair representation: over-representation of government supporters |

| Issue preferences: attitudes towards climate change | |||

| V6: According to a study led by the University of Luxembourg, 77% of the participants think that protecting the environment is more important than providing jobs and economic opportunities. Another survey led among a representative sample of the Luxembourg population indicates that 51% think that economic issues should prime over environmental challenges. | 310 | 13.8 | Unfair representation: over-representation of pro-climate views |

| Control group | |||

| No information | 326 | 14.5 | |

| Follow-up question: acceptance of the mini-public policy recommendations | |||

| How likely it is that would personally accept the policy recommendations produced by a Citizens’ Assembly like the KBR? | |||

| 0: very unlikely that I accept/10: very likely that I accept | |||

Descriptive similarity hypothesis (H4)

The second set of subgroup effects considers whether the respondents are informed about the representation of their own group within the mini-public. We expect them to be egotropic and therefore to only react when they learn that the inclusion of the group to which they belong (their in-group) is ensured. What would matter is that there are people ‘like me’ represented in the process. Receiving information on the presence of participants who share similar social backgrounds and experiences should trigger a positive stimulus, making people perceive that their interests will be considered in the final decisions and hence will be more accepting of these outcomes. Appealing to this sense of ‘shared fate’ is crucial for sortitioned bodies’ legitimacy (Pow 2021). Evidence somehow supporting this claim has been provided by Pow and colleagues (2020) who illustrated that citizens like participants more than politicians because they perceive them to be more alike. Therefore, our expectation within this logic is that citizens’ evaluation of mini-public outcomes will be influenced positively when they learn about the fair presence of participants belonging to the same groups as them.

Hypothesis 4. Information about (a) the fair representation of respondents’ in-group within the mini-public will increase their willingness to accept the policy recommendations, whereas (b) as a corollary, unfair representation of their in-group will decrease it.

Cognitive dissonance X descriptive similarity hypothesis (H5)

Finally, building on the previous argument related to cognitive dissonance, one could expect that the ‘like me’ effect will work with the prior attitudes held about the mini-public. On the one hand, learning about the presence of the in-group should influence positively the outcome acceptance of ‘participatory skeptics,’ as this positive stimulus enters in conflict with their initial negative judgment and could push them to adjust their opinions. Indeed, once these negative respondents are ensured that they are one way or another represented in the process, they should turn more acceptant of the policy recommendations that are made. By contrast, learning about the fair presence of the in-group should have no impact on the ‘participatory enthusiasts,’ as it just confirms their initial positive opinion. However, their willingness to accept should decrease once they learn that their in-group is not fairly represented and hence receive a negative stimulus that contradicts their initial, positive stance.

Hypothesis 5. Information about: (a) the fair representation of respondents’ in-group within the mini-public will increase the willingness to accept the policy recommendations among the ‘participatory skeptics’, whereas (b) as a corollary unfair representation of the in-group will decrease it among the ‘participatory enthusiasts.’

Research Design

The KBR study

In 2022, the government of Luxembourg commissioned a national Citizens’ Assembly on Climate (Klima BiergerRot – KBR). Sixty citizens living or working in Luxembourg were selected and tasked with discussing the country’s current commitments on climate change and developing potential additional measures for Luxembourg’s climate policy. Although three mini-publics were organized by academics or civil society organizations before, the KBR was the first ever organized directly by national political authorities (Paulis, Kies & Verhasselt 2024). Besides, the KBR was the first deliberative process to enjoy media visibility and political impact due to the direct role played by the Luxembourg Prime minister, Xavier Bettel, in promoting this initiative and in announcing that the recommendations would be directly integrated into the discussion in parliament and in cabinet for Luxembourg strategy to fight climate change (Paulis, Kies & Verhasselt 2024). This configuration offered a unique momentum to survey citizens relatively unfamiliar with mini-publics (and hence not influenced by past experiences) and to see how their attitudes towards such a process would evolve when they receive new information about a real-life mini-public that could have direct policy consequences. Besides, this context increases the chances that respondents took seriously when they were asked, in our survey, about their willingness to accept the policy recommendations that the KBR will be making.

We thus seized the opportunity to set up a panel study of the Luxembourg population, to see in real-life conditions how public opinion was reacting to the occurrence of the KBR. Respondents were surveyed (online) three times.2 First, 3025 respondents were interviewed in January–February, at the start of KBR. A second wave (N = 2250) was held in May–June 2022, in the middle of the process. The last wave was conducted in November 2022, once the recommendations were voted on, published, and discussed in parliament. Quota sampling (based on age, sex, professional occupation, region of residence, and nationality) was used to guarantee the representativeness of the sample of respondents (see Appendix 1).

The experimental manipulation and the selection of the vignettes’ attributes

At the beginning of the second wave, we embedded one experimental task (see Table 1 for a detailed summary). The choice to use wave 2 was mainly to avoid any contamination effect.3 A brief introduction informed first all the respondents about the KBR as a Climate Citizens’ Assembly composed via sortition and its advisory role for Luxembourg climate policy. Because our experiment relies on a real case of mini-public that attracted some visibility, it is worth noting that our respondents were not entirely ignorant about the KBR, even more so considering that the survey company oversaw the KBR recruitment and that some media had already reported on the event at the time (Paulis, Kies & Verhasselt 2024). About 70% of the sample reported having heard about the KBR in wave 2 (+34% increase compared to wave 1).4 Yet, their factual knowledge was relatively limited, with a mean score of one correct answer out of the three questions measuring more objectively the accuracy of their knowledge.5 Therefore, this introduction text was important for all respondents to begin with equal access to information.6 Then, we split the sample and randomly assigned respondents to seven experimental groups. The control group received no further information about the KBR composition, whereas each of the six other treatment groups received a vignette describing the actual statistical distribution of one specific characteristic among (a) the KBR participants and (b) the Luxembourg population (see Appendix 2 for a thorough justification of the choices made regarding the different groups/characteristics presented in each vignette). In both cases, we used real figures. Statistics for socio-demographic traits were provided by the KBR organizers and official national statistics. For political traits (political interest, satisfaction with government, and attitudes towards climate change), we used the results of the first wave of the KBR members’ and population survey conducted in parallel. To avoid ethical concerns related to deception, we did not manipulate these figures. After the exposure to this piece of information, respondents were asked a follow-up question on their willingness to accept recommendations that would be produced by a Citizens’ Assembly like the KBR, with a response scale ranging from 0 (very unlikely to accept) to 10 (very likely).

Operationalization of the variables and modelling strategy

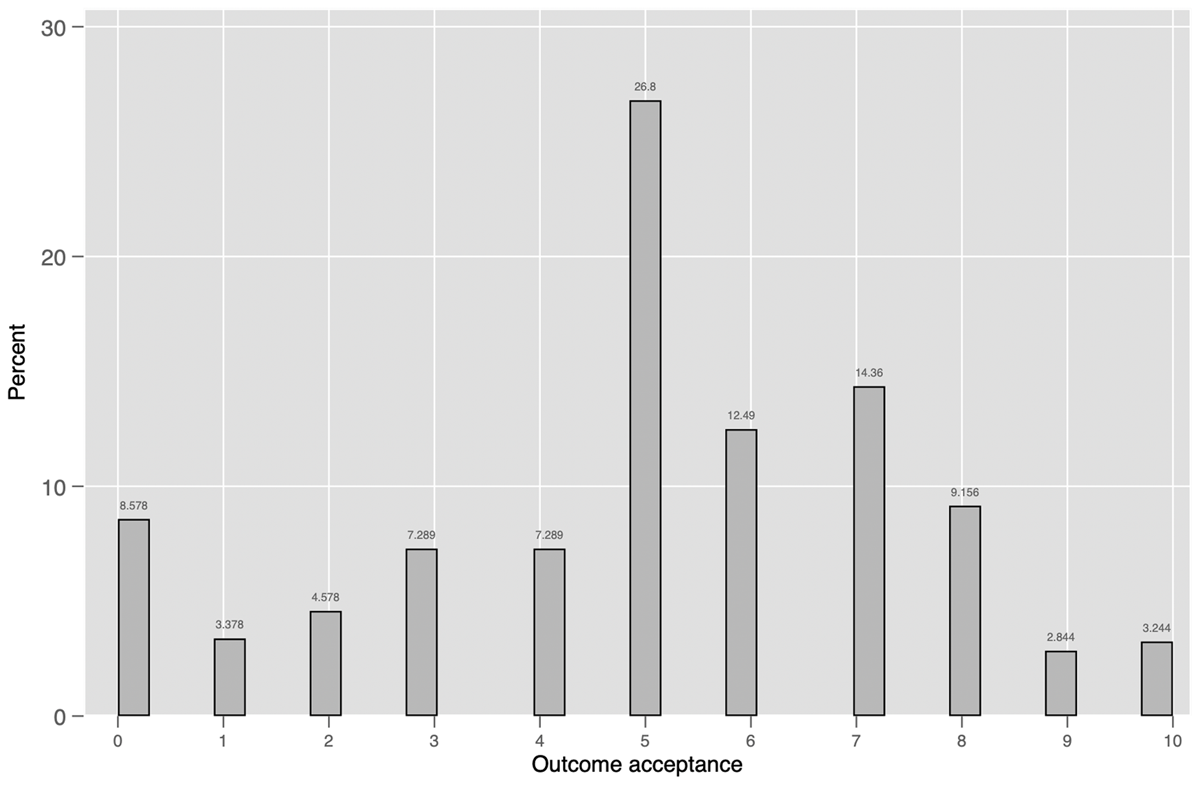

Our main dependent variable is how much respondents are willing to accept (0–10 scale) the policy recommendations that will be formulated by a Citizens’ Assembly like the KBR. Here, we replicated the same wording and scaling as previous studies (e.g., Germann, Marien & Muradova 2022; Pow, van Dijk, & Marien 2020; Van Dijk & Lefevere 2022), where outcome acceptance was generally used as a larger proxy for the public legitimacy perceptions of deliberative processes. When we did the survey experiment, the KBR policy proposals were not formulated yet. Respondents are therefore not influenced by existing, specific outcomes. They expressed generically how much they consent with policy proposals from a mini-public only based on what they know about the process. The descriptive statistics presented in Figure 1 show that respondents tended to score on average in the middle of the scale and thus expressed a relatively neutral opinion on the question. Yet, the distribution suggests that both negative (outcome reluctance) and positive (outcome acceptance) stances are well present in our sample, with the latter group being slightly more populated than the former.

The treatment variable is the vignette to which respondents are exposed to the composition of the Luxembourg Climate Citizens’ Assembly. The respondents of the control group have received no information regarding the profiles of the participants. These respondents only know that the KBR is composed of citizens selected randomly who are tasked to advise the Luxembourg government on climate policy. In our analyses, they will be our reference group and, as a baseline, are coded with a null value (0). Other respondents were assigned a different categorical value ranging from 1 to 6 depending on the treatment that they received. As reported earlier in Table 1, the first two treatments report either an over-representation of participants with a university degree or an under-representation of citizens with a secondary school degree as the highest diploma. The third vignette is the sole to depict a situation of fair representation and statistical representativeness, with (non-)national citizens being equally present in the KBR and the Luxembourg population. The last three vignettes are about the political profiles of KBR participants and show the over-representation of citizens with high political interest, who are positive about the government, or who hold pro-climate attitudes.

As summarized in Table 2 below, H1 (descriptive representation) can be tested by looking at the effect of all the vignettes. H2 (positive discrimination) can be approached with the first two experimental groups when it comes to sociodemographic traits (presence of lower – disengaged – and higher educated citizens – engaged), and with the last three treatment groups when it comes to political traits (engaged: politically interested, satisfied with government and pro-climate). Switching to subgroup differences, to test H3 (cognitive dissonance), we contrast the main effects of the vignettes depending on respondents’ support for mini-public outcomes before the experimental manipulation. We used their positioning on the Likert scale of the item ‘I am willing to accept the outcomes of Citizens’ Assemblies like the KBR’ in the first wave of our survey. We dichotomized this information to distinguish all the people who (strongly) agreed with the statement and had positive attitudes (= 1, 44% of the sample) from those who opted for the other options, were not willing to accept the outcomes and hence adopt more negative or neutral attitudes (= 0, 66% of the sample). To approach H4 (descriptive similarity), we need to look at the main effects of the treatments considering respondents’ in-group membership. We replicate the analysis considering whether they were exposed to the presence of their in-group (see Appendix 4 for the proportion of respondents treated with the representation of their in-group). Finally, to test the last hypothesis (H5), we conduct again the same analysis while combining the two subsampling. In terms of modelling strategy, we report OLS regression tests to interpret the effect of the treatment variable, using the control group as reference category.

Table 2: Connection between hypotheses and vignettes.

| Treatment condition | Vignettes | Individual conditions | Acceptance | |||

| No information (ref) | = control group | |||||

| H1: Descriptive representation | ||||||

| (a) | Fair representation | 3 | Increase | |||

| (b) | Unfair representation | 1,2,4,5,6 | Decrease | |||

| H2: Positive discrimination | ||||||

| (a) | Under-representation | politically disengaged | 2 | Decrease | ||

| (b) | Over-representation | politically engaged | 1,4,5,6 | Decrease | ||

| H3: Cognitive dissonance | ||||||

| (a) | Fair representation | 3 | Participatory skeptic | Increase | ||

| (b) | Unfair representation | 1,2,4,5,6 | Participatory enthusiast | Decrease | ||

| H4: Descriptive similarity | ||||||

| (a) | Fair representation | 3 | In-group | Increase | ||

| (b) | Unfair representation | 1,2,4,5,6 | In-group | Decrease | ||

| H5: Cognitive dissonance X descriptive similarity | ||||||

| (a) | Fair representation | 3 | Participatory skeptic | In-group | Increase | |

| (b) | Unfair representation | 1,2,4,5,6 | Participatory enthusiast | In-group | Decrease | |

Findings

Main effects (full sample)

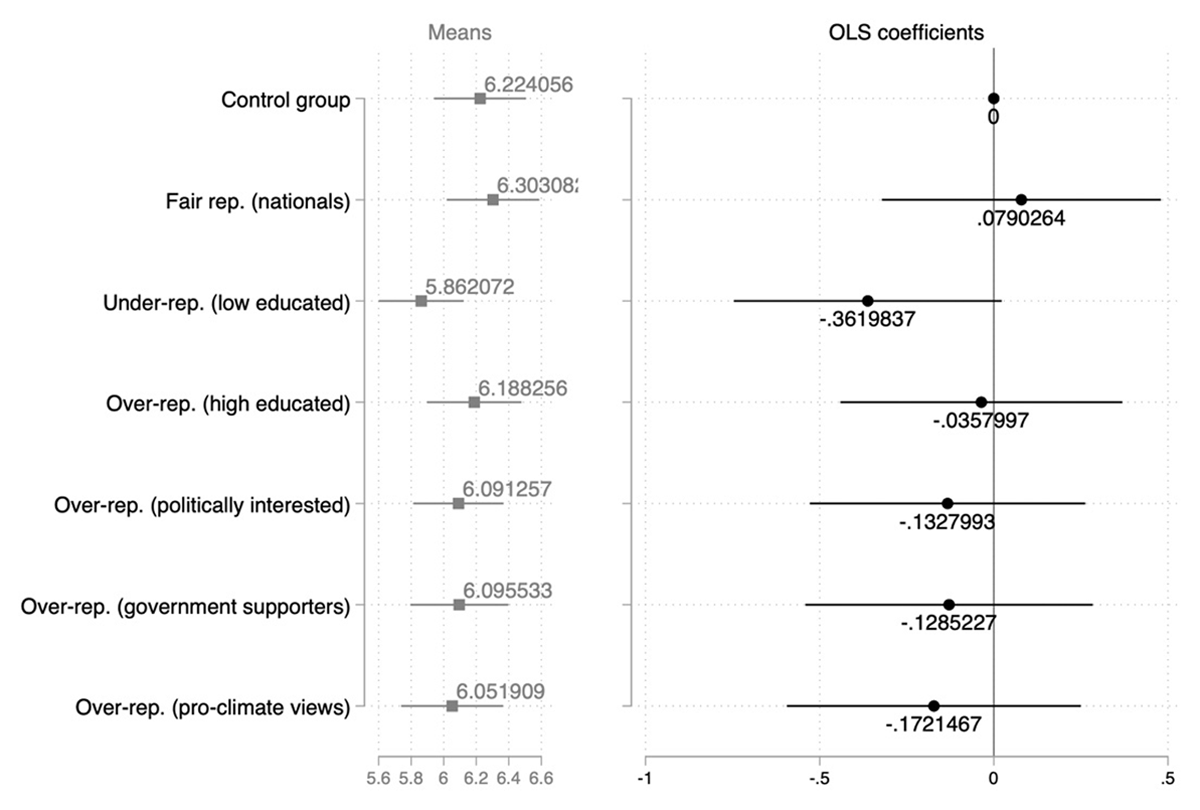

The first set of hypotheses (H1–H2) is interested in the effect of the treatments for all respondents. The analysis reveals, however, no major impact of any of the vignettes on respondents’ generic willingness to accept the outcomes produced by deliberative mini-publics. The right-hand panel in Figure 2 reports the effect of each vignette on our dependent variable compared to the control group.7 For none of the vignettes do we observe a statistically significant difference between treatment and control groups.8 There is no direct evidence supporting our main effect hypotheses related to descriptive representation (H1) or positive discrimination (H2).

Nevertheless, even if the differences with the control group are not statistically significant, the results still go in the expected direction. First, receiving the vignette on fair representation (non-nationals) boosts slightly policy acceptance. As shown in the left-hand panel of Figure 2, the mean score for this treatment is the highest of all groups (6.3) and slightly higher than the control group (6.2). Second, learning about the unfair representation of a group has a small (but non-significant) negative effect on outcome acceptance. The negative effect is the strongest for the vignette about the underrepresentation of participants with a lower level of formal education among KBR participants.

Our take on these first results is that the maxi public does not seem to care much about the mini-public composition to accept the outcomes. This is a non-finding that questions the relevance of descriptive representation as the main linkage mechanism between the maxi and the mini-public, or even whether it is really (only) via the inclusive nature of the process that mini-publics will be able to improve the acceptance of the public policies. At the same time, on a more positive note, employing quotas to make sure that traditionally under-represented groups are included within mini-publics might not harm their perceived legitimacy within the wider public, and might even be important normatively (Smith 2009).

Subgroup effects (subsamples)

Our second set of hypotheses (H3–5) aimed to explore the effect of our treatments on certain subgroups of respondents.9

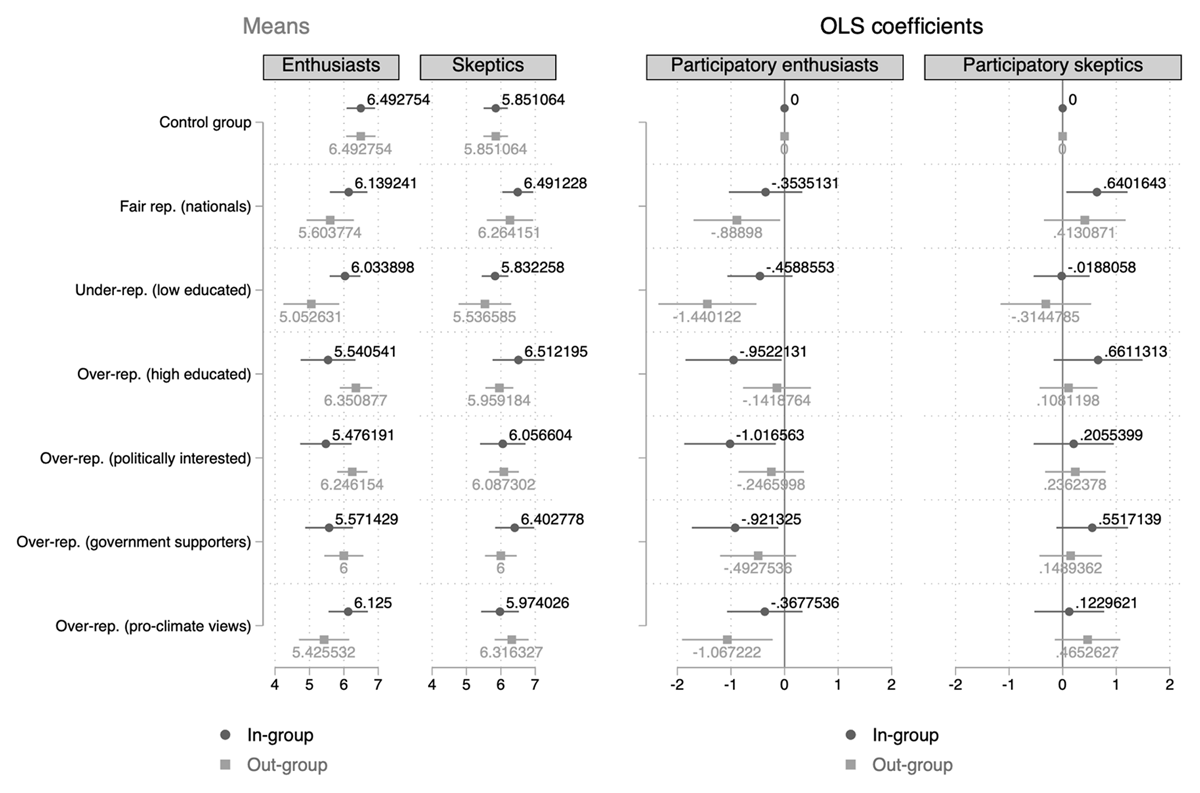

H3: Cognitive dissonance

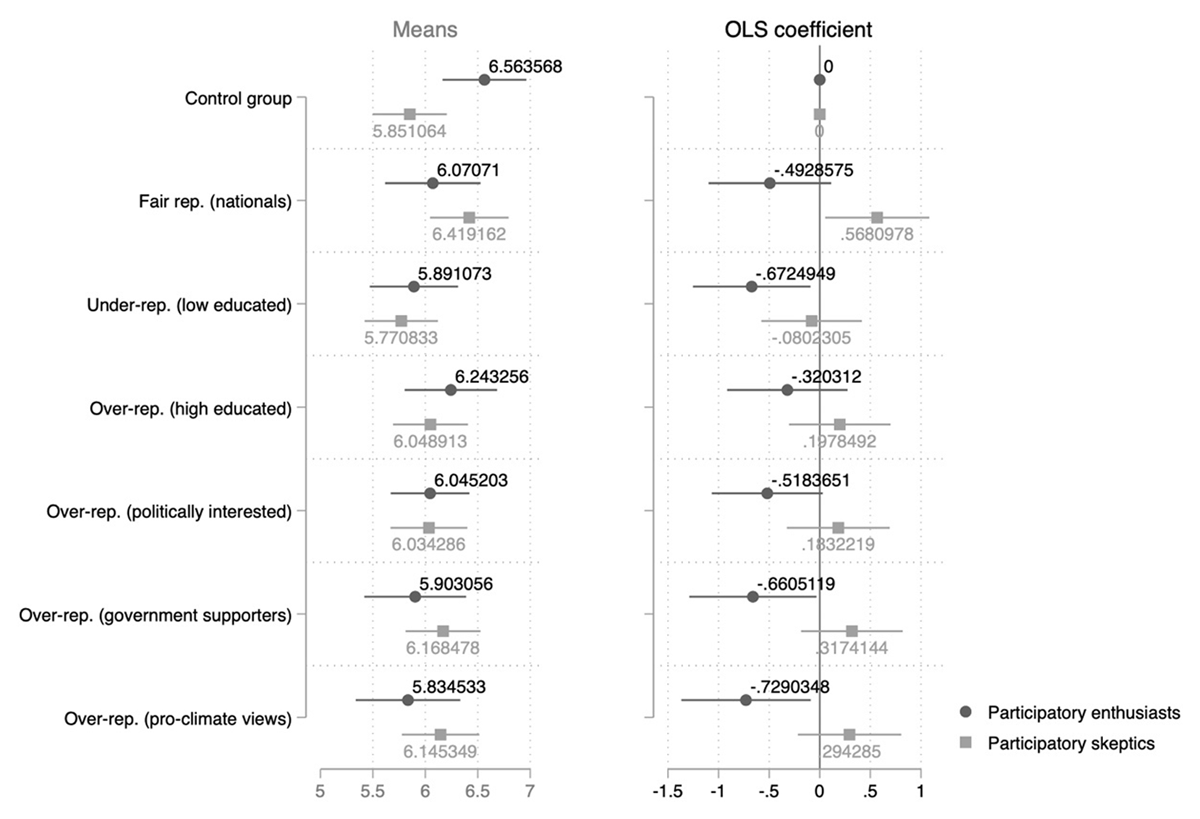

Because our experiment provided new information about the mini-public to panel survey respondents, we have argued via H3 that it might lead respondents to adapt their opinion when they are in a situation of cognitive dissonance, that is, when the message conveyed by the treatment conflicts with their position towards mini-public before that they participated in the experiment. To approach this, we took advantage of the panel structure of our survey and looked at respondents’ attitudes in the first wave. We have therefore split the sample and replicated the same OLS regression distinguishing those who were initially positive towards mini-public and ready to accept the outcomes of these processes (the ‘participatory enthusiasts’) from those who were not and adopted a more skeptical stance (reluctant or undecided/neutral, the ‘participatory skeptics’). The results are exposed in Figure 3.

Regarding participatory skeptics (grey squares in Figure 3), receiving the vignette about the fair representation (of non-nationals) significantly increases outcome acceptance, by 0.5 on average, turning from a 5.9 mean in the control group to a 6.4 in the treatment group (p = .031). It provides full support for H3a. It contrasts with the other vignettes that report on the unfair representation of some groups, which does not change the (already negative) attitudes of participatory skeptics. Those vignettes simply confirm their initial attitudes.

We can then look at the effect of the vignettes on the ‘participatory enthusiasts’ (black dots in Figure 3), that is, respondents who expressed positive evaluations of the mini-public in the first wave of our panel study. Findings reported in Figure 3 show that the exposure to information showing the unfair representation of some groups within KBR negatively impacts their generic willingness to support the outcomes from the mini-public. It is the case when they learned that lower educated citizens are under-represented (p = .023), that government supporters are over-represented (p = .040), or that citizens with pro-climate attitudes are over-represented (p = .026). It confirms H3b and the idea that unfair representation is especially problematic for those who found mini-publics a priori legitimate.

These findings suggest that mini-public composition matters. Not achieving a fair representation of different groups (defined both demographically and politically) could reduce the support for mini-publics among participatory enthusiasts. And achieving it could reduce the skepticism of citizens who are not initially positive about this form of democratic innovation. The results confirm earlier studies showing that non-participants’ legitimacy perceptions of mini-publics increase when they are maximally representative and inclusive (Goldberg 2021). It is therefore crucial to strengthen the communication of mini-publics about their recruitment methods and the profiles that are enrolled (Devaney et al. 2020). Insisting transparently on how mini-publics seek to reach representativeness in recruitment may be an essential strategy to convince citizens less favorable to these participatory processes to embrace their outcomes. And very importantly, our study shows that this fair representation is not only about the sociodemographic traits of participants but also about their political profile, something that is rarely integrated in the recruitment strategies of mini-publics (Paulis et al. 2020).

H4: Descriptive similarity

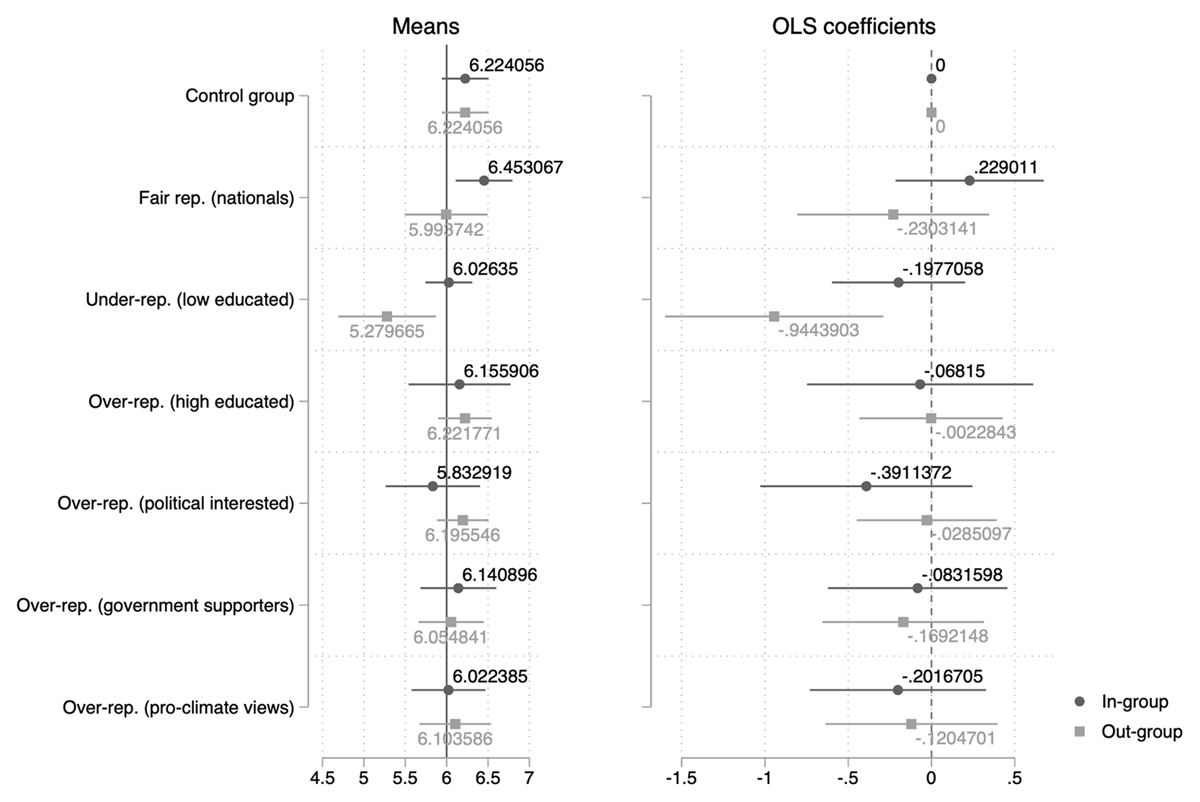

H4 proposes to look for divergent treatment effects depending on whether vignettes contain information about the respondents’ in-group. We thus differentiated respondents exposed to the presence of their in-group from those exposed to an out-group, to which they do not belong. We thus split the sample depending on the congruence between respondents’ own profile and the group about which they were informed in the vignette (see Appendix 3 for wording and operationalization). As for the previous subsample analysis, we replicated twice the same OLS regression to assess the effect of the treatment variable within each of the two groups. The findings are presented in Figure 4.

This exercise did not confirm our expectations. The vignette on fair representation does not produce significantly more acceptance when it mentions the respondents’ in-group (black circles in Figure 4). H4a is therefore not supported. Turning to H4b, our results do not support either that the logic of descriptive similarity would matter more for respondents who belong to a group that is less engaged in politics. If this was the case, non-nationals should then have reacted also positively when introduced to the vignette about fair representation (of nationals and hence of non-nationals), or low educated would have reacted negatively to their under-representation. And we do not observe these patterns.

As the results presented in the right-hand panel of Figure 3 indicate, what we found instead is a significant impact of one vignette for respondents exposed to information about an outgroup. Higher educated respondents who learned that the lower educated were under-represented show significantly lower levels of outcome acceptance. There is a statistically significant difference of almost one point (.94) in comparison to the control group (p = .005). The unfair representation of one group traditionally discriminated in politics (lower levels of formal education) is mainly a source of concern among people who are not discriminated themselves (higher levels of formal education). This finding is surprising because politically engaged individuals usually exhibit more preference for their in-groups and bias against out-groups than do members of politically disengaged groups (Dasgupta 2004). To interpret this, one may return to positive discrimination and argue that citizens from more affluent groups have no real incentive to care about their own representation in mini-publics, as they know that they will be in any case represented within such participatory processes. Hence, they may pay more attention to the inclusion of less privileged groups because it is normatively desirable for the democratic legitimacy of the process and the recommendations that will be produced. The presence of this group of low educated ensures more cognitive and social diversity, which may be important for them to accept the outcomes of this kind of process. This finding points in the direction of an altruistic/sociotropic effect towards disengaged citizens coming from the politically engaged.

H5: Cognitive dissonance X descriptive similarity

Finally, the last expectation (H5) combined both the respondents’ initial attitudes towards mini-public and the in-group presence. We thus replicated the analysis while subsampling on these two aspects.10 The results are presented in the right-hand panel of Figure 5. Looking at the ‘participatory skeptics,’ we found support for H5a. Learning about the in-group representation makes a statistical difference only when the vignette refers to a situation of fair representation. It means that what particularly matters for these skeptical citizens to accept mini-public outcomes is that people like them are not only present in the process but in proportion that makes it fair and representative of the whole population.

We found some support also for H5b when looking at the impact of the vignette on the over-representation of citizens with pro-climate attitudes within KBR. We did not observe any significant effect among the participatory skeptics, but well among the participatory enthusiasts. Especially, respondents who are participatory enthusiasts and climate skeptics turn less willing to accept mini-public outcomes in general when they learned that most KBR participants hold pro-climate views. The vignette does not directly mention the share of their in-group (climate skeptics) within the KBR but they can infer from the large share of pro-climate participants that climate skeptics are under-represented. This situation triggers cognitive dissonance. We have climate skeptics who probably trusted the mini-public to make all views present but then who learned that it was not the case (pro-climate citizens are clearly over-represented) and consequently became more reluctant to accept the outcomes. This finding is crucial not so much for support to mini-publics in general, but for the debates about this form of democratic innovation as a contribution to develop more widely accepted solutions to fight climate change. If climate assemblies (that are multiplying across the globe) fail to attract participants with both pro and anti-climate change views, they are less likely to generate policy support among those who do want to act strongly to fight climate change.

Finally, we have a last significant finding supporting H5b and confirming what we have already found above in Figure 4. Participatory enthusiasts who are highly educated become less willing to accept mini-public outcomes when they learn that there are too many engaged citizens like them among the KBR participants. It translates the opposite of an egotropic effect. They are affected by the representation of citizens unlike them. It was already visible in Figure 4 but becomes even clearer in Figure 5 as the effect is especially strong among highly educated participatory enthusiasts.

The interesting pattern, which we did not observe in Figure 4, is that the same logic seems also to apply to citizens who are participatory enthusiasts and politically interested or supportive of the Luxembourg government. From Figure 5, we can note a significant and negative effect on outcome acceptance for those respondents specifically. Even if the information that they received is positive regarding the representation of their ingroup, they seem to be unhappy with it and would probably like more political diversity among KBR participants.

Conclusion

The goal of this study has been to see whether deliberative mini-publics can really generate public legitimacy and boost policy acceptance. This question has been present in the literature for several years. Existing findings suggested that what mattered the most was the actual content of the policy recommendations formulated (Christensen, Himmelroos & Setälä 2020; Esaiasson et al. 2019). Nevertheless, it has also been shown that the process matters, especially the association of lay citizens to policy-making (Christensen 2020; Esaiasson, Gilljam & Persson 2012; Goldberg 2021; Pow 2021). Building on this last strand of research, the goal of this article has been to look at the input dimension of political legitimacy, which is about who are the actors involved in policy-making (Caluwaerts & Reuchamps 2015). More precisely, we propose to test the general argument that citizens in the broader public will have a positive evaluation of mini-publics and their policy recommendations because of their fair and inclusive composition achieved via sortition (Fishkin 2009). Citizens will appreciate mini-publics as they involve citizens that are broadly representative of the general population, and that are more diverse in their composition than elected institutions by allowing the presence of citizens from all groups within society, even those traditionally less represented in representative bodies.

This argument is often made by proponents of mini-publics and is tested in experimental research using vignettes defining mini-publics as bodies composed of citizens selected by lot (Esaiasson et al. 2019; Goldberg 2021; Ingham & Levin 2018), even sometimes specifying that the group of citizens was representative of the wider population (Pow 2021; Muradova & Suiter 2022). However, the problem with this approach is two-fold. First, it does not consider that most citizens do not know much about mini-publics and which profile of citizens finally compose them. Second, even if mini-publics are often representative of the wider population on core sociodemographic variables (age, gender, region of residence), they are most often not very diverse on other dimensions (education, political attitudes). Therefore, we designed a survey experiment conducted in parallel to a real case of mini-public, the 2022 Luxembourg Climate Citizens’ Assembly (KBR). As part of a panel survey study of the Luxembourg population, we exposed citizens to actual information about the KBR composition and analyzed whether these pieces affected their generic willingness to support the policy recommendations made by mini-publics like the KBR.

The research design developed for this study is, we believe, one important contribution for scholars working on citizens’ attitudes towards mini-publics and other deliberative instruments. Earlier studies have mostly been based on experiments presenting respondents with information about fictional mini-publics (Goldberg 2021; Ingham & Levi 2018; Pow 2021). This approach made sure, first, that citizens who are often unfamiliar with mini-publics would know about their core features. Second, they offer full control to researchers about what factors they can randomize across vignettes. The problem, however, is that it reduces the external validity of findings as we are not sure that respondents would react in real life as they do when exposed to a fictive scenario. We have opted for a different approach, by anchoring our experimental design in a real-life case of a mini-public. Our vignettes presented information about the actual composition of the Luxembourg Climate Assembly (KBR). This approach can work by providing both good information to respondents about what mini-publics are, and by varying the information to which they are exposed (in this case, the profile of KBR participants). This choice enhances the external validity of our findings. Respondents knew that they were asked about something ongoing, and that was supposed to have direct policy consequences, as promoted by the Prime Minister in the media. Such a design leads respondents to think more carefully about the mini-public information they receive and about their willingness to accept the recommendations formulated (Druckman et al. 2011).

In terms of findings, the main observation is that the composition of mini-publics does not seem to be that important for citizens. Our vignettes about the different traits of KBR participants and both situations of fair and unfair representation did not produce visible universal effects. A few earlier studies have shown that the legitimacy of policy decisions could be boosted when citizens are associated (Christensen 2020; Esaiasson et al. 2012). From our study, it appears that learning more about who are those citizens does not provide much added value in boosting policy legitimacy.

The effect of informing on mini-public composition is, however, not completely nil. Especially, running subgroup analyses, we have seen that under certain circumstances who were the KBR participants could matter. Connecting to the concept of cognitive dissonance in social psychology, the mini-public composition matters especially when it contradicts prior attitudes. When Luxembourg citizens initially skeptical about mini-publics were informed that the composition of the KBR was fair on a given attribute, they then became more positive and willing to accept policy recommendations. By contrast, among those who started with positive views on mini-publics, it is learning about the unfair representation of some groups within KBR that impacted (negatively) their attitudes towards mini-publics. They became less acceptant of mini-public outcomes. For example, this dynamic was observed among climate-skeptical citizens who were participatory enthusiasts but then turned more critical when they were informed that KBR was dominated by pro-climate participants. We found the same among other participatory enthusiasts when they learned citizens with higher political interest and higher levels of formal education were over-represented among KBR participants.

Another subgroup effect was detected among respondents with higher levels of formal education. Interestingly, they became less acceptant when they learned that there were very few KBR participants with lower levels of formal education. They reacted in a kind of sociotropic/altruistic perspective as they seemed to care about a group to which they do not belong but are already less represented within representative institutions, stressing that they could pay attention to positive discrimination.

These findings have several important implications for the scholarly and social debates about the capacity of mini-publics to affect the legitimacy of policy decisions. It confirms that how those assemblies are composed does matter and that it may matter both for sociodemographic traits (like education) and political ones (like participants’ attitudes on the topic of deliberation). Yet, the main finding is that this effect is not universal. It very much depends on the recipient’s prior views on such deliberative processes, and on the nature of the participants’ trait that is mentioned in the piece of information received. For scholars, this finding invites future studies to be much more detailed in the information provided about mini-public participants. Only mentioning that they are citizens selected by lot could have a very different effect than providing more detailed information about who the participants are. This finding also opens the way for more systematic research on what traits of participants seem to have more relevance for citizens in the broader public.

Finally, our findings are also of direct relevance for professionals of deliberative democracy. If the goal is to use mini-publics to facilitate policy acceptance in the broader public on some important and complex topics (see Muradova & Suiter 2022), it is highly relevant to care about how they are composed and who is involved. First, additional efforts should be made for having more diverse and representative mini-publics, on a wide variety of traits (demographic and political). New design techniques might help in that respect (Bächtiger et al. 2014; Flanigan et al. 2021; Smith 2009). Second, when fair representation is achieved, communicating clearly about it might have a positive effect, and could even convince some skeptical citizens. Some works have indeed emphasized that the communication about the citizens’ enrolment in Citizens’ Assemblies could be sensibly enhanced (Devaney et al. 2020). Efforts in both directions could contribute directly to having deliberative processes with a real impact on strengthening the legitimacy of public decisions in the eyes of the public.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Representativeness of the sample (wave 2).

| Sample | Population* | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 49.0 | 50.0 |

| Male | 51.0 | 50.0 |

| Age | ||

| 16–24 years old | 10.0 | 12.0 |

| 25–34 years old | 17.0 | 19.0 |

| 35–44 years old | 18.0 | 19.0 |

| 45–54 years old | 17.0 | 18.0 |

| 55–64 years old | 18.0 | 15.0 |

| 65 years old + | 20.0 | 18.0 |

| Education | ||

| low (max 2nd cycle) | 41.0 | 36.0 |

| middle (max bac +3) | 20.0 | 24.0 |

| high (max bac +4 or higher) | 39.0 | 40.0 |

| Nationality | ||

| National (only Luxembourg citizenship) | 66.0 | 54.0 |

| Non-national (other citizenship(s)) | 34.0 | 47.0 |

| Region | ||

| Luxembourg-City | 17.0 | 20.0 |

| Center | 16.0 | 16.0 |

| South | 36.0 | 37.0 |

| North | 16.0 | 15.0 |

| East | 14.0 | 12.0 |

| Occupation | ||

| In paid work (active) | 53.0 | 57.0 |

| Not in paid work (inactive) | 47.0 | 43.0 |

* The population data are based on the official population census from Statec or the OECD. The figures are those used by the survey company to apply the quota in recruiting respondents from their online panel. They were provided with the report of their fieldwork.

Appendix 2. The selection of the social and political attributes displayed in the vignettes

A key challenge when we designed the experimental manipulation was the selection of the groups that should be displayed in the vignettes. Our selection was guided by three principles. First, we wanted to create vignettes related to the socio-demographic profiles of KBR participants, especially about groups that are systematically under-represented in representative institutions. Second, building on the recent literature about the overwhelming presence of politically engaged citizens in mini-publics, we also decided to create vignettes about those groups of citizens (Fourniau 2019; Jacquet 2017; Walsh & Elkin 2021). Finally, following Pow and colleagues’ claim (2020) that some criteria might matter more in the composition of the mini-public in relation to the issue at stake, we decided to select participants’ traits that are more relevant to climate change policies.

Regarding socio-demographic traits, we know that climate policy preferences differ between low and high educated groups (Colvin & Jotzo 2021; Dechezleprêtre 2022; Gifford & Nilsson 2014). Moreover, climate policies have distributional effects implying that low education categories are disproportionally affected (Vona 2023). Besides, democratic judgments are more generally influenced by education-based descriptive representation (or the lack thereof), while education is a good vehicle for group identification (Mayne & Peters 2023). In addition, highly educated people are more likely to participate in deliberative mini-publics (Walsh & Elkink 2021) and are often overrepresented (Fourniau 2019), whereas the low educated are more difficult to recruit and retain (Visser, de Koster & van der Waal 2021). Therefore, we decided to report on participants’ education (V1 and V2 in Table 1 in the main text), with one vignette showing the proportion of low educated and one showing the high educated. The two vignettes reveal a condition either of slight over-representation of the high educated group (+10 pc points compared to population) or of under-representation of the low educated (–10pc points). It is worth noting that education was not part of the recruitment quotas, the company in charge having preferred to use professional activity. Second, the Luxembourg population is very peculiar because there are many non-national citizens who either reside or come daily to the country for working purposes, are therefore excluded from the electoral process and have low leverage on Luxembourg politics (Kankarash & Moors 2010), but still are impacted by government policies. More precisely, this part of the population is very mobile and could thus even more be concerned by climate policies and their representation in the decision-making process. Furthermore, much of the cultural minorities are generally found in this specific section of the population. The issue of their participation in national politics became particularly polarizing along with the referendum hold in 2015 where Luxembourg citizens were consulted regarding the voting rights to be granted to non-nationals and finally rejected the constitutional reform’s proposal. We thus decided to have another vignette reporting on the nationality of the participants, also because the cultural background can be particularly important for the assessment of minorities’ presence. In this respect, the data used in the vignette (V3 in Table 1 in the main text) offers a condition of perfect statistical representativeness, with the proportion of nationals among the participants (and hence of non-nationals) being equal to the population, stressing probably also the importance of this trait in the recruitment of KBR members.

Besides the representation of certain social groups, we earlier argued that it was important to enlarge the picture to the representation of political and climate attitudes. Some research shows a positive correlation between interest in politics and awareness of environmental issues as well as acceptance of climate policies (Douenne & Fabre 2022). At the same time, political interest (like education) is a strong determinant of participation in mini-publics (Walsh & Elkink 2021), and as a result deliberative processes are often largely populated by people expressing high level of subjective interest. Consequently, one vignette provided information on the presence of people interested in politics (V4 in Table 1 in the main text). The latter shows a strong discrepancy (+19pc points) between the mini and the maxi public and a condition of over-representation of people very interested in politics. Furthermore, like for any type of public policies, we know that the (non-)acceptance of policies for environmental protection strongly connect to political (dis)trust (Fairbrother et al. 2021; Otto & Gugushvili 2020). In parallel, public attitudes towards sortitioned bodies is highly related to how trustful citizens are towards representative institutions (Pilet et al. 2021). Recent research shows that ‘deliberative democrats’ willing to engage in participatory processes tend to be more confident in representative institutions (Rojon & Pilet 2021; Walsh & Elkink 2021). Therefore, another vignette exposed respondents to the representation of people supporting the government. The information provided in this vignette (V5 in Table 1 in the main text) reveals a condition where people trusting the government are over-represented, by about 20pc points compared to the general population. Finally, we know that citizens value substantive representation more robustly than descriptive representation in decision making processes (Arnesen et al. 2019). The last vignette expands thus to the representation of climate attitudes among participants. Studies show that beliefs and factual knowledge about the environmental challenges are generally strong predictor of climate action and acceptance of climate policies (Bumann 2021; Ding et al. 2011). Furthermore, ‘deliberative democrats’ is the group of citizens that appear to care the most about the environment compared to the groups declaring other democratic preferences (Rojon & Pilet 2021). Our last vignette (V6 in the main text) shows indeed that there was an over-representation of people holding positive stances towards climate change among the participants (+26pc points), and therefore that more skeptical opinions were less represented.

Appendix 3: Description of experimental groups’ composition (means).

| Gender | Age | Professional activity | Income | Left-right placement | Political trust | Political efficacy | KBR knowledge | |

| Range | 0–1 | 1–7 | 0–1 | 1–5 | 0–10 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 0–1 |

| Control | 0.52 | 3.89 | 0.57 | 3.67 | 4.26 | 2.65 | 3.74 | 0.76 |

| V1 | 0.53 | 3.88 | 0.53 | 3.55 | 4.61 | 2.54 | 3.65 | 0.73 |

| V2 | 0.50 | 3.99 | 0.51 | 3.65 | 4.31 | 2.65 | 3.72 | 0.74 |

| V3 | 0.53 | 3.94 | 0.54 | 3.59 | 4.50 | 2.64 | 3.73 | 0.76 |

| V4 | 0.53 | 3.84 | 0.54 | 3.55 | 4.45 | 2.77 | 3.78 | 0.77 |

| V5 | 0.52 | 3.90 | 0.54 | 3.64 | 4.35 | 2.64 | 3.72 | 0.72 |

| V6 | 0.52 | 3.84 | 0.53 | 3.63 | 4.39 | 2.68 | 3.75 | 0.84 |

Appendix 4: Distribution of individual-level traits across experimental groups.

| Full sample |

0 Control |

V1 High educated |

V2 Low educated |

V3 Nationals |

V4 Very interested in politics |

V5 Government supporters |

V6 Pro-climate |

|||||||||

| N | % | N | % | % | % | % | % | % | N | % | ||||||

| Education11 | ||||||||||||||||

| Low degree attainment (below) | 1,717 | 77.4 | 248 | 77.5 | 253 | 78.3 | 269 | 78.2 | 232 | 78.9 | 272 | 80.2 | 238 | 78.2 | 205 | 71.2 |

| High degree attainment (< = bachelor) | 499 | 22.6 | 76 | 22.5 | 70 | 21.7 | 75 | 21.8 | 62 | 21.1 | 67 | 19.8 | 66 | 21.8 | 83 | 28.8 |

| Nationality12 | ||||||||||||||||

| Non-national | 747 | 33.2 | 101 | 33.2 | 109 | 33.0 | 120 | 34.5 | 106 | 35.5 | 110 | 31.9 | 101 | 33.0 | 100 | 34.3 |

| National (Lux citizenship only) | 1,503 | 66.8 | 225 | 66.8 | 222 | 67.0 | 228 | 65.5 | 193 | 64.5 | 235 | 68.1 | 209 | 67.0 | 191 | 65.7 |

| Interest in politics13 | ||||||||||||||||

| Not (at all) interested | 1,645 | 74.5 | 242 | 74.5 | 234 | 72.7 | 256 | 76.0 | 221 | 75.7 | 250 | 73.7 | 223 | 72.6 | 219 | 76.3 |

| (Very) interested | 562 | 25.5 | 81 | 25.5 | 88 | 27.3 | 81 | 24.0 | 71 | 24.3 | 89 | 26.3 | 84 | 27.4 | 68 | 23.7 |

| Satisfaction with government14 | ||||||||||||||||

| Not (at all) satisfied | 1,293 | 58.3 | 180 | 58.2 | 181 | 59.9 | 196 | 57.2 | 171 | 58.2 | 205 | 59.9 | 189 | 61.3 | 171 | 59.8 |

| (Very) satisfied | 923 | 41.5 | 141 | 41.8 | 137 | 40.1 | 147 | 42.8 | 123 | 41.8 | 137 | 40.1 | 119 | 38.7 | 115 | 40.2 |

| Attitudes towards climate15 | ||||||||||||||||

| (Strongly) disagree with the pro climate statement (or neutral) | 1,080 | 48.8 | 138 | 42.9 | 165 | 51.0 | 176 | 51.1 | 158 | 54.5 | 170 | 49.8 | 131 | 43.1 | 142 | 49.3 |

| (Strongly) agree with the pro climate statement | 1,132 | 51.2 | 184 | 57.1 | 158 | 49.0 | 168 | 48.9 | 132 | 45.5 | 171 | 50.2 | 173 | 56.9 | 146 | 50.7 |

| Outcome acceptance (W1)16 | ||||||||||||||||

| Not willing to accept (or neutral) | 1,262 | 56.1 | 188 | 57.7 | 184 | 55.6 | 192 | 55.2 | 167 | 55.8 | 175 | 50.7 | 184 | 59.3 | 172 | 59.1 |

| Willing to accept | 988 | 43.9 | 138 | 42.3 | 147 | 44.4 | 156 | 44.8 | 132 | 44.1 | 170 | 49.3 | 126 | 40.6 | 119 | 40.9 |

Note: Grey cells indicate respondents exposed to information about their in-group. Endnotes describe the exact wording of the related survey questions.

Appendix 5: Number of observations per analytical subgroups (H5).

| Participatory enthusiasts | Participatory skeptics | |||

| Control | (N = 138) | (N = 198) | ||

| In-group | Out-group | In-group | Out-group | |

| High educated | Low educated | High educated | Low educated | |

| V1 – high educated | 25 | 114 | 45 | 139 |

| Control | 32 | 108 | 44 | 140 |

| Low educated | High educated | Low educated | High educated | |

| V2 – low educated | 131 | 29 | 138 | 46 |

| Control | 108 | 32 | 140 | 44 |

| V3 – nationals | National | Non-national | National | Non-national |

| 90 | 39 | 103 | 67 | |

| Control | 101 | 40 | 124 | 61 |

| V4 – politically interested | Interested | Not interested | Interested | Not interested |

| 38 | 100 | 51 | 150 | |

| Control | 35 | 104 | 46 | 138 |

| V5 – gvmt support | Pro-gvmt | Anti-gvmt | Pro-gvmt | Anti-gvmt |

| 53 | 92 | 66 | 97 | |

| Control | 61 | 76 | 80 | 104 |

| V6 – pro-climate | Pro-climate | Skeptics | Pro-climate | Skeptics |

| 58 | 82 | 88 | 60 | |

| Control | 71 | 67 | 113 | 71 |

| 395 | 456 | 491 | 559 | |

| Total N | 989 | 1248 | ||

Appendix 6: Full outcomes of the regression analyses.

| Full sample | Subsample 1 | Subsample 2 | ||||||||||||||

| In-group | Out-group | Participatory skeptics | Participatory enthusiasts | |||||||||||||

| Mean | OLS coefficient | p value | Mean | OLS coefficient | p value | Mean | OLS coefficient | p value | Mean | OLS coefficient | p value | Mean | OLS coefficient | p value | ||

| Control (ref) | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 5.8 | 6.5 | |||||||||||

| Fair representation | Statistical rep. of nationals | 6.2 | .07 (.20) | .697 | 5.9 | –.19 | .497 | 6.3 | .22 | .327 | 6.4 | .57 | .031 | 5.9 | –.49 | .111 |

| Unfair representation | Under-rep. of low educated | 5.8 | –.34 (.19) | .066 | 5.9 | –.20 | .319 | 5.3 | –.82 | .010 | 5.7 | –.08 | .752 | 5.8 | –.67 | .023 |

| Over-rep. of high educated | 6.1 | –.02 (.19) | .894 | 6.1 | .01 | .971 | 6.0 | –.07 | .822 | 6.0 | .20 | .440 | 6.1 | –.32 | .292 | |

| Over-rep. of gvmt supporters | 6.1 | –.05 (.19) | .513 | 6.1 | .04 | .827 | 5.8 | –.32 | .272 | 6.0 | .18 | .480 | 6.1 | –.52 | .065 | |

| Over-rep. of politically satisfied | 6.0 | –.09 (.20) | .426 | 6.0 | –.12 | .588 | 6.0 | –.05 | .833 | 6.1 | .32 | .215 | 5.8 | –.66 | .040 | |

| Over-rep. of pro-climate | 6.0 | –.09 (.19) | .545 | 6.0 | –.10 | .702 | 6.0 | –.07 | .761 | 6.1 | .30 | .259 | 5.8 | –.73 | .026 | |

| Anova p value | .477 | .902 | .095 | .232 | .231 | |||||||||||

| Constant | 6.1 | .000 | 6.1 | .000 | 6.1 | .000 | 5.8 | .000 | .000 | |||||||

| R2 | 2.5 | 1.4 | 10.4 | 6.4 | 8.5 | |||||||||||

| N | 2,250 | 1,558 | 1,041 | 1,262 | 988 | |||||||||||

| Subsample 3 | Participatory skeptics | Participatory enthusiasts | ||||||||||||||

| In-group | Out-group | In-group | Out-group | |||||||||||||

| Mean | OLS coefficient | p value | Mean | OLS coefficient | p value | Mean | OLS coefficient | p value | Mean | OLS coefficient | p value | |||||

| Control (ref) | 5.8 | 5.8 | 6.5 | 6.5 | ||||||||||||

| Fair representation | Statistical rep. of nationals | 6.5 | .64 | .028 | 6.2 | .41 | .289 | 6.1 | –.35 | .311 | 6.3 | –.88 | .031 | |||

| Unfair representation | Under-rep. of low educated | 5.8 | –.01 | .944 | 5.5 | –.31 | .466 | 6.0 | –.46 | .139 | 5.0 | –1.44 | .002 | |||

| Over-rep. of high educated | 6.5 | .66 | .118 | 5.9 | .11 | .695 | 5.5 | –.95 | .038 | 5.6 | –.14 | .660 | ||||

| Over-rep. of politically interested | 6.0 | .20 | 590 | 6.1 | .23 | .412 | 5.5 | –1.0 | .020 | 6.2 | –.25 | .429 | ||||

| Over-rep. of politically satisfied | 6.4 | .55 | .105 | 6.0 | .15 | .617 | 5.6 | .92 | .025 | 6.0 | –.49 | .173 | ||||

| Over-rep. of pro-climate | 5.9 | .12 | .711 | 6.3 | .46 | .136 | 6.1 | .37 | .306 | 5.4 | –1.06 | .013 | ||||

| Anova p value | .170 | .619 | .115 | .011 | ||||||||||||

| Constant | 5.8 | .000 | 6.1 | .000 | 6.4 | .000 | 6.5 | .000 | ||||||||

| R2 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 1.9 | 2.7 | ||||||||||||

| N | 700 | 766 | 535 | 598 | ||||||||||||

Notes

- https://lequotidien.lu/a-la-une/citoyens-decus-debat-reporte-le-klima-biergerrot-prend-leau/. ⮭

- The questionnaires and sample characteristics were defined by our research team. Data were collected by the survey provider TNS-ILRES based in Luxembourg. The survey was proposed in the three official languages (French, German, and Luxembourgish), and English. ⮭

- The choice to include our vignette experiment in the second wave of the panel survey was guided by three elements. First, via wave 1, we captured attitudes about mini-publics months before the experimental treatment to avoid direct contamination effects. Second, in wave 2, we had clear information about the profile of KBR participants (based on information provided by the organizers or by the first wave of the members’ survey for political and climate attitudes), which was needed to design our vignettes. Moreover, we had our first wave that could serve as benchmark to compare KBR participants’ climate and political attitudes to the general population in the vignettes. Third, when wave 2 was fielded, there had already been some media coverage about what the KBR was, but the outcomes were still not determined (in contrast to wave 3). This prevents any contamination based on the coverage of the policy recommendations. It therefore maximizes the chances of isolating the effect of our vignettes on the profile of KBR participants on respondents’ attitudes towards KBR. We cannot rule out any effect of other external factors but our design, and the choice of wave 2, tries to minimize that risk. ⮭

- The question was: Since the beginning of the year 2022, Luxembourg organized a national citizens’ assembly. It brought together a group of citizens to deliberate and provide recommendations for addressing a specific policy issue. Before this survey, had you ever heard of this citizens’ assembly that is now taking place in Luxembourg? Yes/No. ⮭

- The questions dealt with their knowledge of the policy issue that was debated (Which of the following issues are discussed by people participating in this citizens’ assembly? List of policy issues), the recruitment method (How have the participants of this citizens’ assembly been selected? List of proposals) and the commissioning body (Do you know who has initially decided to create this citizens’ assembly in Luxembourg? List of proposals). ⮭

- As reported in Appendix 2, a similar level of KBR knowledge is found in all experimental groups. ⮭

- All the regression tables are provided in Appendix 6. ⮭