Introduction

The idea of deliberative democracy relies heavily on attitude transformation, here defined broadly as shifts or switches in agreement with reasons, discoursers or values underlying policies, as well as with specific policy options. An openness among deliberators to transform their attitudes, by being responsive to and recognizing merits in arguments put forward by others, is considered pivotal in the pursuit of defining a ‘common good’ or a ‘public will’ (Barabas 2004; Gutmann & Thompson 1996; Fung 2003; Mansbridge et al. 2010). Agreement among autonomous individuals who exercise communicative rationality, that is, engage in comprehensive, sincere and truthful exchange of views, is argued to possess legitimacy beyond that derived from majority-rule voting (Cohen 1989; Habermas 1984). In policy-oriented texts on deliberative planning, attitude transformation is implied in prescriptions of citizen dialogue as a means for mutual agreement (e.g., OECD 2020; SALAR 2019). In this literature, the non-coercive characteristics of deliberation are frequently contrasted with top-down policy implementation by planners and other experts; with hierarchical policy instruments such as command-and-control legislation; or with economic incentives and information campaigns that exercise influence in predefined directions.

Critique against the reliance on voluntary attitude transformation through communicative rationality, and thereby explicitly or implicitly against the ideal and practices of deliberative democracy, can be found in both democracy theory and behavioral science. Difference democrats such as Mouffe (2005) hold that political conflicts cannot be overcome through rational consensus as idealized by Habermas. Instead, they call for agonistic debate and a continuous openness to perspectives that challenge hegemonic norms and discourses. In planning theory, a stream of research warns that careless application of deliberative ideas may create democratic facades that legitimize decisions taken elsewhere, or provides already strong societal groups with arenas to exercise illegitimate power (e.g., Huxley 2000; Hillier 2003; Tewdwr-Jones & Allmendinger 1998;). Adding to these critical voices, there are ample empirical studies demonstrating how people who engage in political dialogue do not necessarily conform to communicative rationality, but instead are subject to various biases that cast shadows of doubt upon the practical feasibility of deliberation (e.g., Giljam & Jodal 2003; Rienstra & Hook 2006; Zajonc 1999).

To scrutinize whether mechanisms influencing deliberators’ attitudes in real-life settings are compatible with assumptions underlying deliberative democracy is arguably a central task for political science and planning scholars. It is a large and complex task with many entry points, some of which involve deep-going philosophical questions about rationality; autonomy and formation of will (see Rostbøll 2005). The present paper will restrict its focus to a seemingly neglected aspect of this issue, namely deliberators’ awareness of whether their own attitudes transform through dialogue.

This inquiry rests on the hypothesis that the level of deliberators’ awareness signals whether criteria of communicative rationality are fulfilled, and hence can serve as an indicator of deliberative quality. Indeed, the significance of awareness can be directly derived from central ideas in deliberative theory, including the Habermasian requirement for sincerity and authenticity of validity claims – a requirement that arguably presupposes that persons making these claims are mindful of what they believe and desire. Accordingly, Riensta and Hook (2006, p. 313) stipulate that ‘no validity claims are redeemable between communicative participants if the agent cannot access, substantiate or understand their own rationality’. The requirement for awareness can also be linked to, for example, Elster (1983), who asserts that rational formation of preferences must be intentional and autonomous; to Dryzek (2002, p. 162), who notes that ‘authenticity of deliberation requires that communication must induce reflection upon preferences in a non-coercive fashion’; and to Christman (2009), who states that the desires of an agent are authentic if s/he can reflect upon the historical process that caused them without feeling alienated from it.1

Nevertheless, deliberators’ awareness of attitude transformation has received little direct attention in literature. While the study of deliberative groups has seen significant methodological progress over recent decades, the issue is not accounted for in approaches to identify, measure and evaluate attitude transformation – the Q-methodology that focuses on how changes in discourses can be derived from changes in deliberators’ attitudes towards more particular propositions (Dryzek 1990; Dryzek 2005a); the deliberative quality index that focuses on fulfilment of procedural criteria drawing on Habermasian discourse ethics (Steenbergen et al. 2003); and the deliberative reasoning index that focuses on intersubjective consistency among deliberators regarding preferences for policies and considerations underlying these policies (Niemeyer & Dryzek 2007). Further, while recent handbooks on deliberative democracy (Bächtiger et al. 2018; Levy et al. 2018) comprehensively deal with prospects for conscious deliberation, they do not address the more specific issue of recognizing and interpreting deliberators’ self-awareness of attitude transformation. That said, even though few authors explicitly discuss the issue, both theoretical and empirical studies illuminate factors that help explain whether participants in political dialogue become aware of any attitude transformation, and, if so, whether they are willing to acknowledge this to others. The present paper is an attempt to combine findings of these studies into a heuristic model that can guide further inquiry into the issue.

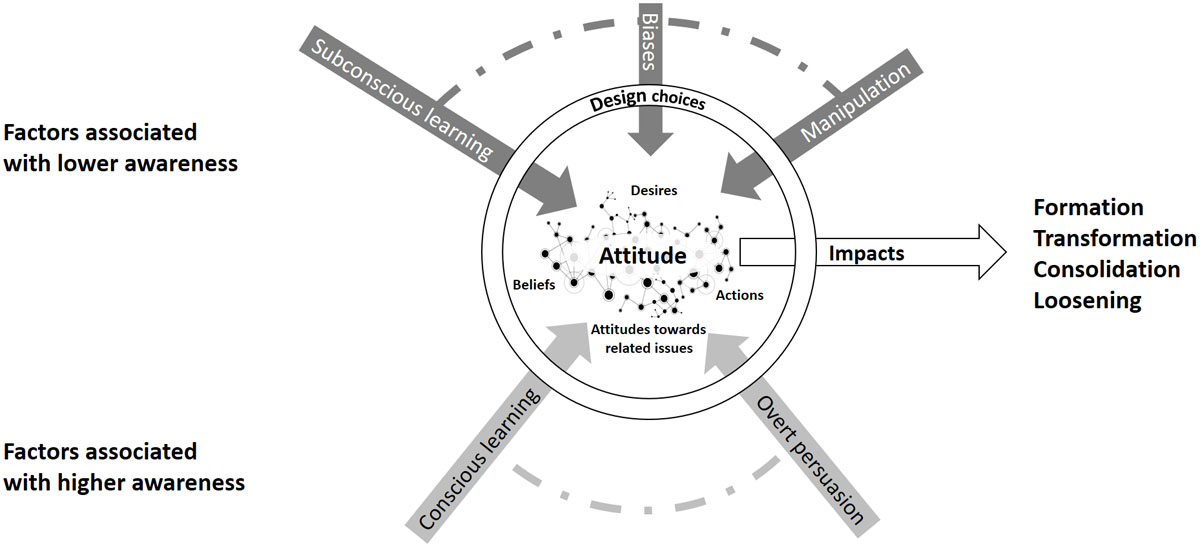

In this heuristic, as outlined in the coming sections, I will conceptualize learning as a fundamental mechanism mediating any impacts from deliberation on attitudes. These potential impacts include formation of new attitudes as well as consolidation, loosening or transformation of preexisting attitudes. Drawing on a notion of learning as meaning making based on both conscious and subconscious clues, I will assert that deliberators are unlikely to be fully aware of these impacts, or be able to attribute them to specific deliberative occasions. In literature on deliberative democracy, I discern three overall factors of relevance for the level of such awareness – one that should heighten it and two that may lower it. The awareness-supporting factor is the conscious reasoning on arguments laid out as overt and justified persuasion in accordance with communicative rationality. The hampering factors are, first, various subconscious biases inherent in social processes in general and political dialogue in particular, as described in behavioral research; and second, the potential calculated manipulation of participants that political dialogue lends itself to, as warned for by critical scholars. The extent to which these overall factors come into play during deliberation may in turn be partly controlled, or at least influenced, by design choices of those in charge of setting up dialogues.

Beyond the paper’s theoretical focus, for illustrative purposes, I also present empirical results from a minor explorative study of two Swedish citizen dialogues (in total 24 respondents) that prompted the conceptual investigation. While the samples are too small for firm inference, the observations indicate that level of discordance between revealed and stated switches in attitudes may be a viable vantage point for exploring the concepts of the heuristic model in real-life dialogue settings. More specifically, differences between the two dialogues tentatively corroborate earlier suggestions that attitude transformation is less likely in ‘hot’ dialogues around well-defined contested political issues than in dialogues characterized by broader topics and less friction among participants, but also that the awareness of any transformation might be higher in the former case.

Deliberation as Learning

Learning is arguably a defining feature of deliberation, and consequently ubiquitous, if not always explicit, in deliberative democracy research. This learning not only encompasses sharing or jointly creating knowledge on the subject matter, but also improved understanding of views and values of fellow deliberators (e.g., Mansbridge et al. 2012), as well as, at a meta level, the practice of deliberation itself – that is, what Owen & Graham (2015) call ‘the deliberative stance’. Still, elaborate discussions on the more specific dynamic between the interlinked processes of learning and attitude transformation are not common in deliberative democracy literature. According to Wright (2022), theory often assumes that deliberation is about debating and justifying standpoints formulated prior to deliberation, as opposed to new ideas emerging along the way. At the same time, several authors highlight how people’s stands on political issues are often ill-formed, incomplete or conflicting (Bartels 2003; Cuppen 2012; Feldman & Zaller 1992; Lavine, Johnston & Steenbergen 2012). The alleviation of such ambiguity, as well as construction of identities through formation of preferences, is seen as an important learning potential in deliberation (Fishkin 1995; Karpowitz & Mendelberg 2018; Prior & Lupia 2008; Rostbøll 2005). Using Wright’s (2022) terminology, if this potential is realized, impacts on attitudes can be attributed to ‘co-creation’ of views, rather than to persuasion based on the ‘force of the better argument’ (Habermas 1996). Connected to this reasoning, correlations presented by Luskin et al. (2002) indicate that deliberators who learn more in terms of acquisition of facts also tend to change their attitudes more, while Zhang (2019) shows that uninformed opinions are more susceptible to influence through deliberation than well-founded opinions.

Just as in everyday language and in policy pertaining to deliberation (e.g., OECD 2020), the term learning is typically surrounded by positive connotations in deliberative democracy research, signaling a better-informed basis for attitudes and their amendment. For example, in the context of deliberative polling, Luskin et al. (2002; p. 474) assert that ‘The rationale of Deliberative Polling requires that such [policy preference] changes be not merely random bouncing around, nor the outgrowth of some purely social dynamic, but rather the product of learning and reflection, of coming to see consequences for valued goals more clearly and weigh them more carefully […]’. Some deliberative democracy papers, however, acknowledge that learning per se does not necessarily impact attitudes in accordance with communicative rationality, for example, as it may derive from skewed information (Strassheim 2020). Smets and Isernia (2014) show that in relation to some issues, participants calibrate new information conveyed through deliberation with ideological predispositions, thereby enforcing their preexisting views, while in other cases, learning may instead moderate and nuance attitudes. Westwood (2015) argues that links between knowledge acquisition in deliberation and opinion changes are generally weak, making the case that persuasion through justified arguments is instead the main driver of attitude transformation.

In education theory, the question how classroom activities designed as deliberation intentionally or unintentionally may shape political attitudes has seen an increased interest in recent decades. Transactional and other learning theories that draw on pragmatism, including Dewey’s works on linkages between democracy and education (e.g., Dewey 1916), as well as on Habermasian discourse ethics, conceptualize education that encourages a plurality of perspectives as the key mechanism for learning (e.g., Englund 2000; Gutmann 1999). Acknowledging an entanglement of facts and values in such classroom deliberation, research on these theories harbors a debate on how teachers should handle the normativity that is inherent, but not necessarily overt, in education on political issues, such as sustainable development (e.g., Hellquist & Westin 2019; Jickling & Wals 2008).

Connected to the more specific issue of awareness of attitude transformation, studies of cognitive aspects of learning demonstrate how it stems from both conscious and subconscious processes involving perceptions, language, memories, emotions and motivations (e.g., Kuldas et al. 2013), and is therefore ‘explicit’ as well as ‘implicit’ (Seger 1994). In a strict sense, it can thus be asserted that it is impossible for learners to fully deduct and account for effects of a specific deliberative occasion. This assertion is further strengthened upon a closer look at the psychological origin of attitudes towards political issues, which Eagly and Chaiken (1993) describe as an interplay between beliefs, desires, actions and preexisting attitudes towards other, related issues. Learning prompted by deliberation may affect one or several of these ‘attitude components’, but this may not be directly noticeable, let alone manifested, as shifts or formation of fully developed attitudes. Instead, it can be assumed that impacts are often indirect, latent and non-linear, and therefore may be difficult to attribute to a particular deliberative occasion for both deliberators and researchers (Chambers 1996; Mackie 2006). As an example of this, Mugny and Perez (1991) describe how a dialogue on abortion did not change the position of participants opposing decriminalization, but made them more favorable towards contraceptives, even though the latter issue was not explicitly mentioned during discussions.

In sum, the reviewed literature supports a conceptualization of learning as a fundamental mechanism that mediates any impacts from deliberation on attitudes (cf. Bohner et al. 2002). These potential impacts include attitude transformation, that is, shifts or switches in position on political issues at hand, but also formation of attitudes that were previously non-existent or obscured; as well as affirmation and consolidation of preexisting attitudes, or, conversely, loosening of preexisting attitudes through increased ambiguity. Being a broad concept, learning does not necessarily confirm with communicative rationality, since both cognitive input and internal sense making can be distorted. Moreover, as learning stems from both conscious and subconscious clues, it can realistically be assumed that rather than fully aware, deliberators will be cognizant of impacts on attitudes to a lesser or greater degree, depending, for example, on to what extent they engage in ‘internal deliberation’ following dialogue with others (Goodin 2000). In the following two sections, I review literature suggesting that this level of awareness depends on to what extent overt persuasion in accordance with communicative rationality is distorted by, first, unintentional socio-psychological biases, and, second, calculated manipulation.

Deliberation versus Biases

As touched upon in the introduction, behavioral research has revealed a plethora of phenomena that may influence participants in political debate independent of rational reasoning on the subject matter. These include, but are not limited to, ‘group polarization’ (the tendency of like-minded deliberative groups to become even more homogeneous and move in the direction of initial predispositions due to social dynamics; Schkade, Sunstein & Hastie 2010; Sunstein 1999); ‘adoption by attribution’ (valuation of arguments based on relationship with and perceived status of the source; Tooming 2021); ‘motivated reasoning’ (valuation of arguments based on a strive to maintain group identities; Kunda 1990; Wright 2022); ‘social intuitionism’ (founding of moral judgements on intuition, with rational motivation lacking or being construed post hoc to justify the intuitive judgement; Haidt 2001; Lodge & Taber 2013); and ‘adaptive preferences’ (contingency of preferences upon limited options available; Elster 1983; Knight & Johnson 1997). Underlying these phenomena are well-known more general psychological biases, such as confirmation bias, in-group bias, observational-selection bias, framing effects and rationalization.

Results from these studies are not necessarily coherent, and therefore difficult to synthesize into general conclusions, as they depend on contexts of investigated cases. Still, the divergence in scholarly assessments of their implications on overall prospects for deliberation is striking. For example, in their influential contribution to the ‘realist’ stream of critique against deliberative democracy, Achen and Bartels (2017) assert that hopes to achieve communicative rationality in real life settings are utopian and naïve in light of biases, unstable political preferences and generally low levels of knowledge among citizens. Along similar lines, Riensta and Hook (2006, p. 314) propose that ‘[…] Habermas’s construction of communicative rationality rests upon an agent role that might only be filled in reality by a self-reflexive critical genius. Deliberative agents are assumed to be heroic in terms of informational breadth and calculative abilities, and heroic in their ability to identify, segregate and set-aside self-interest. This agent might be an individual of Habermasian proportions and Habermasian abilities, but they are no agent of modern actuality.’

From the other side of this debate, advocates of deliberative practice have responded, first, that communicative rationality represents an ideal to be approximated and not an assumption about typical human behavior (e.g., Chambers 2018; Sharon 2019). Second, some scholars highlight the potential of deliberation to instill social norms that ‘launder’ participants’ preferences and prevent them from expressing biases related to, for example, prejudice or selfishness, thereby fulfilling a ‘second-order preference’ for high quality dialogue (Goodin 1986). Third, pertaining to the more specific phenomena listed above, proponents of deliberation can invoke studies suggesting that these biases can be abated, or at least managed at acceptable levels, through careful design of deliberative interaction. For example, Imbert et al. (2020) show how misrepresentation of deliberators’ true attitudes, which may stem from adoption by attribution or motivated reasoning, can be counteracted by ensuring sufficient opportunities for expression of minority attitudes. Luskin et al. (2022) show that deliberative polls are resilient to polarization and homogenization, while Himmelroos and Christiansen (2014) and Strandberg et al. (2019) demonstrate how rules enforcing ‘deliberative norms’ in political dialogue may curb polarization also in like-minded groups. Khader (2018) suggests that cross-cultural deliberation can enable criticism of adaptive preferences and revelation of unrecognized alternative paths to well-being, while McHugh et al. (2017) propose that social intuitionism expressed as ‘moral dumbfounding’ can be countered by demanding that deliberators provide justifications for their judgements. Dryzek (2005b) discusses how the level of contestation may affect deliberators’ openness to revise their attitudes. He asserts that this is harder in ‘hot’ dialogue settings, that is, when stakes are high, discussions are directly linked to decision making, and partisans are involved. He therefore proposes that deliberation should take place in ‘colder’ contexts at a certain distance from formal decisions. Fung (2003) tentatively takes the opposite view, suggesting that hot dialogues may be more transformative as they are engaging and creative, although he also acknowledges a lack of comparative empirical studies of attitude transformation in hot and cold dialogues. In their critical account of polarization through deliberation, Schkade, Sunstein and Hastie (2010) instead argue that expectations to arrive at decisions might amplify herding biases, if deliberators feel pressed not to obstruct the process – an example of the paradoxical, subtly coercive, ‘chilling effect’ that may arise from excessive emphasis on consensus (Dahlgren 2009; Morrissey & Boswell 2020).

In what ways, then, can attendance to deliberators’ awareness of attitude transformation contribute to an advancement of this debate? Operating at a subconscious level per definition, to the extent biases come into play, they will tend to obscure this awareness, and, conversely, the level of awareness will reflect prevalence of biases. Putting aside the harshest critique of deliberative democracy, the implication of which is that a vast majority of initiatives will be futile or outright harmful, and instead stipulating that distortion from biases varies depending on contextual factors, eliciting awareness of attitude transformation can help assessing whether levels of such distortion are acceptable or unacceptable. In this regard, it should prove a viable complement, if not error proof, to other indicators of deliberative quality. More specifically, if observed attitude transformation in an individual deliberator seems prompted by group dynamics such as herding or polarization, while the deliberator is reluctant or unable to acknowledge the transformation, this signals deviation from communicative rationality. However, before conclusions are drawn, methodological limitations of what realistically can be elicited should be considered, as discussed below, as well as the possibility of intentional manipulation, as discussed in the next section.

Several of the biases listed above prompt deliberators’ subconscious tendencies to either align with or maintain a distance to views of other individuals or groups, disregarding rational reasoning on the subject matter. In other cases, based on the same motives, the biases may instead obstruct attitude transformation that would have taken place if founded solely on rational deliberation. Discordance between acknowledged and observed attitude transformation will be visible to the extent that biases in play during deliberation can be lessened or eliminated in the setting where deliberators are asked directly whether their attitudes have changed (such as in a research interview or in a questionnaire). Admittedly, this prerequisite will not always be possible to meet or control. For instance, illustrating what Mackie (2006) calls ‘the unchanging mind hypothesis’, that is, the frequent, but not necessarily valid, notion that deliberation rarely alters anyone’s standpoint, people might be reluctant to admit changes in views on high-stake political issues not only to fellow deliberators and researchers, but also, at the conscious level, to themselves. A main reason for this phenomenon suggested by Mackie (ibid.) is the strive for consistency, which is directed both inwards, as a means to preserve self-image, and outwards, as consistency is closely related to credibility and integrity, which are highly valued in political debate. To assess such cases, more sophisticated methods than the ones sketched here are needed. In other cases, it is conceivable that deliberators will acknowledge that their attitudes have transformed even though this was sparked by subconscious bias. Here, assessment would rely on presence, quality and timing of justifications of these transformations, in order to detect, for example, post hoc rationalization.

One additional methodological caveat, demonstrated by Goodin and Niemeyer (2003) and Niemeyer (2020), warrants mentioning. In one of very few empirical studies dealing explicitly with alignment between observed and stated attitude transformation, the authors investigated a citizens’ jury process concerning a road through a wilderness area. Goodin and Niemeyer (2003) found that observed shifts in 12 jurors’ agreement with propositions on various aspects of the road did not align with their stated attitude change.2 Revisiting the data, Niemeyer (2020) instead compared the jurors’ stated change with revealed preferences regarding i) five policy alternatives for the future of the road, including an option to close it; and ii) only the choice between closing and keeping it. While stated attitude change again did not align with change in preferences for the five options, it did so with switches between the binary close/keep options. The explanation put forward by Niemeyer is that when stating attitude transformation, deliberators may restrict their focus to a single policy choice considered of paramount importance compared to other topics addressed in dialogue.3 More study is needed to determine if such a pattern reflects unawareness of less significant transformation, or if it rather represents a response heuristic.

Deliberation versus Manipulation

Deliberative initiatives that enable communicative rationality can be construed as the very opposite of manipulation (Fishkin 2010). At the same time, deliberation is susceptible to illegitimate influence through distortion of participants’ attitudes. For example, populists may take calculated advantage of the biases discussed above, by inciting in-group bias vis-a-vis perceived outgroup elites, or by strengthening support for one-sided arguments through confirmation bias, thereby exacerbating polarization. Sharon (2019) shows that concern over such corruption of attitudes has since long been present also among proponents of deliberation, and he asserts that the risk of manipulation constitutes the single most serious challenge to deliberative democracy, as it threatens its core function of transforming independent judgment of deliberators into collective self-government through reasoning.

The concept of manipulation encompasses several related phenomena, but it is not easy to pinpoint denominators that are common to all (Noggle 2022). Manipulation can be levied directly at individuals or executed indirectly through modification of their physical or institutional environments. It can be defined as action along the spectrum between overt rational and sincere persuasion and coercion, and as such, it often aims at bypassing deliberative reasoning among target groups. This can be achieved by appealing to non-conscious emotions or hiding relevant information. Manipulation may also be executed through open argumentation, then instead being characterized by intentions that are hidden from its targets, or by deceiving messages that trick targets into beliefs that the manipulator knows are flawed. Further adding to the complexity is the question whether manipulation is always morally wrong, or if there are cases where it may be legitimate, such as if outcomes favor its targets.

In deliberation, participants may be subject to manipulation from outside actors, from other participants, or through calculated choices by those designing and facilitating dialogue. Providing examples of the last possibility, Ellul (1962/2021) describes dialogue practices in Mao’s China that functioned to influence participants in predefined ways. As opposed to top-down propaganda, these practices relied on horizontal mechanisms of establishing and reinforcing certain attitudes among participants, supervised by discussion leaders who directed conversation towards topics and conclusions that were acceptable from the state ideology standpoint. He and Warren (2011) assert that such ‘authoritative deliberation’ is still prevalent in Chinese governance, the main purpose of which is to legitimize already taken decisions or provide information that increases top-down policy implementation capacity without empowering participants to have an independent say. Corresponding phenomena are by no means absent in western contexts, as discussed in several studies (e.g., Boussaguet 2016; Franzén, Hertting & Törn 2016; Polletta 2014; Swyngedouw 2018; Walker et al. 2015).

Responding to the concerns about manipulation, some scholars have suggested that deliberation should be restricted to ‘constitutional’ aspects of governance, that is, those pertaining to fundamental principles underlying other legislation and executive and administrative power, as they may be less prone to corruption and more engaging to the average citizen (Ackerman 1991; see further in Sharon 2019). Other proponents of deliberation instead trust the ability of deliberative practice to withstand manipulation, or correct calculated distortion of attitudes, and they can invoke several empirical studies in support of this view (Dryzek et al. 2019). For example, Niemeyer (2004; 2011) shows how mini-publics may realign attitudes distorted by symbolic politics with deliberators’ true preferences for policy outcomes, while Fishkin (2018) demonstrates that support for populist policy proposals may decline following deliberation. In terms of deliberative designs that may help curbing manipulation, Niemeyer and Jennstål (2018) suggest that the focus of deliberative mini-publics should not be to recommend or decide on specific policies, but to explicate and scrutinize reasons underlying relevant policy options, thereby exposing attempted manipulation. They further emphasize the safeguarding of a ‘deliberative stance’ as a key antidote to manipulation among participants in dialogue, much along the same lines as described in relation to unintentional biases in the previous section.

Central to this deliberative stance is the rejection of ‘strategic rationality’, that is, deception, threats of sanction, or other tactics that treat fellow deliberators as means to other ends than reasoned agreement (Dawood 2013; Habermas 1984). At the same time, the line between communicative rationality and strategic rationality is not always clear-cut in practice. Blau (2019) convincingly argues that certain features attributed to strategic rationality in theory on deliberation are not always true, including fixed ends and self-interest. Conversely, communicative rationality may involve self-interest as well as certain strategic means-to-end considerations, for example, regarding which linguistic means best convey validity claims. Instead, Blau asserts that the two key features distinguishing strategic and communicative rationality is that the latter requires, first, sincerity of validity claims; and, second, that any agreement with these validity claims is voluntary and autonomous. Of relevance to this assertion is the scholarly debate on to what extent rhetoric should be allowed in political dialogue (Chambers 2009). Difference democrats, such as Young (1997), have argued that deliberative demands on rational communication are technocratic, dull and excluding. They suggest that that a broader communicative repertoire, including humor, word play, figures of speech and storytelling, may increase engagement, reflection, and involvement of stakeholders with different styles of expression, including groups not used to arguing as prescribed by theory. This view has been adopted, at least in part, also by some proponents of deliberation, including Dryzek (2002), who even mentions gossip (p. 1) as an acceptable form of deliberative communication, although he also warns that rhetoric may coerce participants by manipulating their emotions. Going one step further, Casullo (2020) conceptualizes deliberation as a public performance where bodily communication should be more acknowledged. Thereby, she arguably stretches current definitions, while also highlighting the potential for populist modes of persuasion to influence deliberators.

Now, returning to the inquiry of the present study, in what ways is deliberators’ awareness of attitude transformation relevant for concerns about manipulation? As evident from the reviewed literature, manipulation of deliberators can be either hidden or overt. In the latter case, if deliberators are faced with explicit but false claims regarding outcomes of policy choices under discussion, or if they are openly threatened with sanctions if not aligning their views to those of the manipulator, they will in most cases be aware of these influences. Then, potential manipulation can be assessed based on, for example, discrepancy between preferred and likely outcomes of their policy choices, in line with the methods applied by Niemeyer (2004; 2011), or, more generally, critical assessment of how deliberators motivate their transformation, if at all. The latter approach should be viable also if deliberators acknowledge that their attitudes have changed, but are unable to identify the underlying reasons, as the means of influence have been hidden by a manipulator. If deliberators do not at all acknowledge their own attitude transformations as observed or revealed by a researcher, and these transformations correspond to intentional choices by those designing dialogue regarding, for example, the framing of the topic or dominant views among recruited participants, this may indicate hidden manipulation. Lastly, attention to deliberators’ awareness of attitude transformation could be useful also at the micro-level, when addressing the thorny question of acceptable rhetoric in deliberation. Manipulative elements disguised as rhetoric might be indicated by such things as difficulties among participants to provide rationales for attitude transformations that appear to stem from intuitive or affective reactions to arguments (cf. Manin 1987), or by transformations that appear guided by distorted interpretations of intentions and commitments underlying arguments, to the extent this can be reliable assessed by the researcher.

Summary: A Heuristic for Awareness of Attitude Transformation

Figure 1 attempts to give an overview of key concepts and mechanisms outlined in the literature reviewed above. Naturally, it represents a considerable simplification in relation to actual intricate interplays between attitudes and conscious and subconscious influencing factors during deliberation. As denoted by the dashed lines, factors influencing attitudes associated with higher and lower levels of awareness, respectively, are interlinked. For example, overt persuasion can induce conscious learning through reasoning, whereas both subconscious learning and hidden manipulation might spark biases that are also subconscious. In addition to serving as a vantage point for further inquiry into awareness of attitude transformation, the heuristic symbolizes that choices of those designing and facilitating deliberation affect how the factors come into play.

Illustrative Case: Observations from Two Swedish Citizen Dialogues

To introduce a few tangible, if tentative, ideas on how deliberative designs can influence awareness of attitude transformation, and on how this awareness can inform assessment of deliberative quality, the remainder of this paper is devoted to a brief account of two minor Swedish municipal citizen dialogues. Although not its main focus, the study of these dialogues elicited attitude transformation as changes in agreement with propositions regarding the topics, as well participants’ self-assessment of their attitude transformation. The literature review above was prompted by a curious difference in the alignment of these revealed and stated attitude transformations between the two dialogues.

Empirics and Method

The study was conducted within the frames of a project run by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR) over the years 2015–2018 to support municipalities implementing citizen dialogues on conflictual societal issues. Two dialogues were followed particularly close: one in the municipality of Svenljunga and one in the municipality of Fagersta. Methods included direct observation of dialogue occasions, interviews with involved civil servants and questionnaires aimed at participants. These questionnaires were distributed to citizens who took part in start-up meetings – 25 persons in Fagersta and 15 persons in Svenljunga. Of these, 16 persons in Fagersta and eight persons in Svenljunga answered both the pre and post dialogue questionnaires, corresponding to response rates of 64% and 53%, respectively.

Prior to the start-up meetings, civil servants in each municipality interviewed large numbers of citizens to identify relevant ‘perspectives’ (defined broadly as both general views and policy preferences) on the issues to be addressed, including conflicting ones. The compiled perspectives also served as a basis for the research questionnaires, where a subset of perspectives reflecting key challenges related to each issue was included as propositions (without any editing by the author). Respondents’ level of agreement with each proposition were stated on Likert scales taking on the levels ‘Fully agree’, ‘Somewhat agree’, ‘Somewhat disagree’ and ‘Fully disagree’, along with an ‘I don’t know’ option. In the post-dialogue questionnaires, respondents were further asked open-endedly if the dialogue had affected their attitudes, and they were also prompted to motivate how or why not (the word ‘affected’ was purposefully chosen in order to capture both switches and shifts, cf. discussion below).4 The post-dialogue questionnaire also included an open-ended question whether respondents had gained new knowledge during the dialogue.

Key Observations

While the two dialogues shared important features in terms of preparations, they also differed in fundamental respects. Most importantly, two distinct issues were addressed. In Svenljunga, the objective was to reach consensus on how to organize schooling across the municipality. As in other rural areas in Sweden, Svenljunga faces the challenge of increasing costs for upholding schooling in villages as number of children decline. At the same time, closing of rural schools is met with resistance as they are seen as vital for small villages in terms of, for example, identity and space for social interaction. In Fagersta, the objective of the dialogue was to identify measures for inclusion of marginalized groups. As other Swedish municipalities, Fagersta experienced an inflow of immigrants in 2015, which was variably perceived by citizens as either a social and economic opportunity or as a challenge related to pressure on social welfare systems and tension between ethnic groups, for example. The dialogue was named ‘Inkludera flera’, which translates to ‘Include more [people]’, and in communication material on the process, a distinction between integration and inclusion was adopted, signaling an ideal where minority groups not only take part in society on equal terms (integration) but merge with majorities through exchange of cultures and norms (inclusion).

The ambition to involve opposing perspectives on the two issues was seemingly achieved to a higher degree in Svenljunga than in Fagersta. As revealed through questionnaires and observations, both citizens advocating and opposing closing of rural schools were present in Svenljunga. Moreover, politicians representing parties with opposing views on the issue participated. As agreed beforehand, they were not very active, in order not to turn the deliberation into political debate, although they did gave occasional remarks to clarify the positions of their respective parties. While other perspectives on schooling were part of the initial scope, already at the onset of the first meeting, discussions gravitated towards the rural school issue. After a few occasions, it became clear that consensus could not be achieved. Instead, subgroups holding opposing views were encouraged to develop separate proposals to be considered in a draft strategic plan for schooling.

In Fagersta, the focus remained rather broad over the dialogue. As the collected perspectives were deemed too diverse to be covered given a limited number of participants, a prioritization was done in the first meeting. The resulting shortlist included the topics of employment, parenthood, schooling, and spaces for social interaction. Notably, participants opted not to address a subset of perspectives labelled ‘winners and losers’, which made explicit trade-offs related to immigration. Based on interest, participants discussed the prioritized topics in subgroups with the aim of identifying concrete policy measures. Rather than disagreement, discussions were characterized by uncertainty, but each group was able to consensually agree on action points to be submitted to the municipal administration. As for representation of opposing perspectives in Fagersta, a few persons diverged from the majority by agreeing with perspectives articulating negative or skeptical attitudes towards immigrants, but these were not voiced during the dialogue. The only political party represented in Fagersta was the Social Democrats, which held the chair in the municipal executive committee. Invitations to take part were sent out to other parties in the municipal assembly, including the national-populist Swedish Democrats, but these were declined.

In both municipalities, correlations between number of attended dialogue meetings and changes in levels of agreement with questionnaire propositions were positive,5 while stated attitude transformation was uncorrelated with attendance.6 The pattern indicates that the questionnaires were able to capture impacts from the dialogues. That said, both directions of causality between attendance and revealed attitude transformation are conceivable: while it is plausible that participating in more dialogue meetings increases influence on attitudes, it is also possible that persons who are less open to changing their views attend fewer meetings.7 A majority (89.5%) of respondents who did not attend all meetings stated ‘lack of time/other commitments’ as the main reason. Consequently, while aversion to attitude transformation possibly contributed to absence in some cases, I assert that it is unlikely to account for a large proportion of the observed correlation, and the remaining account will thus rest on the assumption that the dialogues indeed transformed respondents’ attitudes to some extent.8

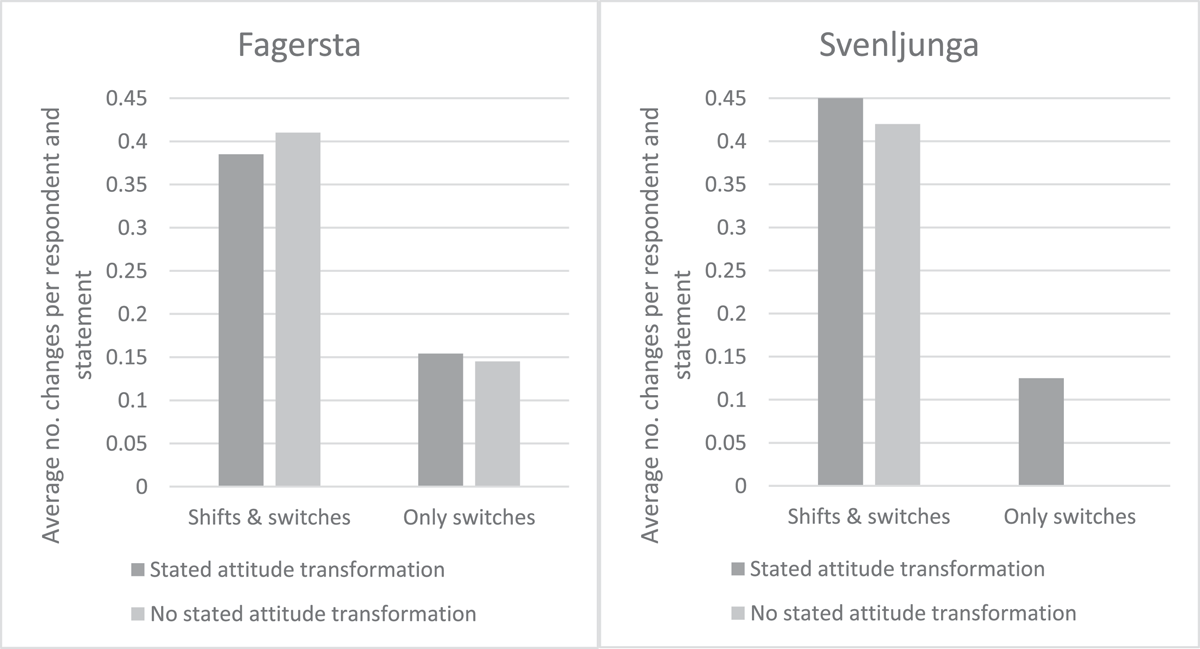

Significant differences related to attitude transformations between the dialogues concerned a higher rate of switches between agreement and disagreement with questionnaire propositions among participants in Fagersta: 75% of respondents here made switches, as opposed to 37.5% in Svenljunga.9 Despite this, a lower share of participants in Fagersta stated that their attitudes had been affected: 31.25% compared to 50% (four persons) in Svenljunga. Figure 2 illustrates alignment between stated attitude transformation and revealed switches. In Fagersta, average rates were similar across respondents who stated that the dialogue had affected their attitudes and those who stated that they were unaffected.10 By contrast, in Svenljunga, three of the four respondents who stated that their attitudes had been affected made one or more switches,11 whereas none of the respondents who stated that they were unaffected made any switches. When looking instead at switches and shifts combined, the difference in alignment between the municipalities disappears.

Table 1 lists the propositions subject to most (three or more) switches in Fagersta and all propositions subject to switches in Svenljunga. Notably, none of the listed propositions from Fagersta are explicitly linked to the subgroup topics. By contrast, three of the four propositions subject to switches in Svenljunga directly concern the rural schools conflict. The small sample in Svenljunga makes confident inference impossible, although the direction of switches of individual respondents suggests that observations are not spurious: one participant switched to from agreement to disagreement with propositions 1 and 2 and from disagreement to agreement with proposition 3, indicating a more positive attitude towards a centralized school organization. Conversely, another participant instead switched to from disagreement to agreement with propositions 1 and 2, suggesting a more negative attitude.

Propositions subject to the highest rates of switches between agreement and disagreement.

| Municipality | Proposition12 | Share of respondents who switched from agreement to disagreement | Share of respondents who switched from disagreement to agreement | Share of respondents who made switches and also stated attitude transformation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fagersta (16 respondents) | 1. Immigrants should be integrated into Swedish society and culture, not the other way around. | 6/16 (37.5%) | 1/16 (6.25%) | 2/7 (28.6%) |

| 2. Resources are too limited, and people in Fagersta become competitors as immigration increases. Many see themselves as victims. | 4/16 (25%) | 1/16 (6.25%) | 2/5 (40%) | |

| 3. Tenants in Fagersta have limited knowledge of rights and obligations. Some do not know how to behave in an apartment. | 2/16 (12.5%) | 3/16 (18.75%) | 2/5 (40%) | |

| 4. Fagersta residents are afraid of new people. | 1/16 (6.25%) | 3/16 (18.75%) | 2/4 (50%) | |

| 5. The only way to alleviate segregation in Fagersta is to mix people in domestic areas. | 3/16 (18.75%) | 0/16 (0%) | 1/3 (33.3%) | |

| 6. Natives Swedes in Fagersta only socialize among themselves and with their families. | 2/16 (12.5%) | 1/16 (6.25%) | 0/3 (0%) | |

| Svenljunga (8 respondents) | 1. Keep rural schools – let teachers and pupils travel there from the central town. | 1/8 (12.5%) | 1/8 (12.5%) | 2/2 (100%) |

| 2. Schools are critical social nodes in small villages – they bring life to rural areas. | 1/8 (12.5%) | 1/8 (12.5%) | 2/2 (100%) | |

| 3. When primary education is distributed across many small villages, resource use becomes inefficient. | 0/8 (0%) | 1/8 (12.5%) | 1/1 (100%) | |

| 4. Parents have little trust in the school system in Svenljunga. | 0/8 (0%) | 1/8 (12.5%) | 1/1 (100%) | |

Estimated interquartile ranges of responses to each questionnaire proposition allow for a rough overall assessment of homogeneity in the subsamples. In Fagersta, variation increased in relation to 23% of propositions, remained unchanged in relation to 38.5%, and decreased in relation to 38.5%. In Svenljunga, the corresponding proportions were 62.5%, 12.5% and 25%. Thus, in Fagersta respondents became slightly more likeminded while the opposite is true for Svenljunga.

In both municipalities, a majority of respondents stated that they had gained new knowledge during the dialogues (87.5% in Fagersta and 75% in Svenljunga). Presumably related to this learning, in Fagersta, the rate of ‘I don’t know’ responses did not change much following the dialogue (however, this seemingly static proportion conceals a few changes that cancel each other). By contrast, in Svenljunga, the rate of ‘I don’t know’ responses decreased, indicating a lowered overall uncertainty.

Discussion

The small sample sizes, especially in Svenljunga, call for caution when interpreting attitude transformation in individual respondents. Still, the overall patterns point to a few avenues worth exploring in future studies. First, from a methodological perspective, that stated attitude transformation aligns with revealed switches but not with revealed shifts among respondents in Svenljunga suggests that this distinction carries meaning. It might complement Niemeyer’s (2020) proposal that respondents focus on prominent policy choices when asked to self-assess attitude transformation; it is possible that they also primarily think of transformations from agreement to disagreement or vice versa. At the same time, in Fagersta alignment was lacking also for switches, suggesting other confounding factors there.

One possibility is that the difference in alignment between the municipalities is linked to lower initial knowledge and less firm opinions on the broader issue of integration, compared to on the more specific issue of rural schools. If so, the higher rate of revealed attitude switches, the lower rate of stated attitude transformation, and the poor alignment between these two parameters in Fagersta could be attributed to less certain and/or conscious á priori views, obscuring subjective experiences of attitude transformation and perhaps substituting them for notions of learning and increased clarity. However, the ‘I don’t know’ option available for each proposition should be able to control for this, at least partly. Instead, the lower initial share of ‘I don’t know’ answers in Fagersta, and the fact that this share did not decrease, does not fit this explanation.

Another possibility relates to the distinction between hot and cold deliberation discussed above. Formally, both dialogues were advisory, with final decisions resting with the municipal assemblies. At the same time, observations suggest that stakes were perceived as higher in Svenljunga, as evident both in the debate during the dialogue and in reports on ongoing protests in affected villages. Further, in Svenljunga, politicians with diverging views were present, while a corresponding partisan tension was lacking in Fagersta. The lower rate of switches and persistent attitude heterogeneity in Svenljunga can possibly be ascribed to a more contested and well-defined policy choice. Further, the observations hint at a possibility that in hot dialogues, pressure on participants from opposing arguments is obvious enough to make attitude switches conscious, compensating for or overriding mechanisms that obscure attitude transformation or discourage participants to admit it to themselves or others. Conversely, in colder dialogues, this pressure may be less obvious and attitude transformation less conscious.

Lastly, the framing of the dialogue topics can be considered. In Fagersta, the direction of the most frequent attitude switches indicate that at group level, participants became more positive towards prospects of successful integration built on a shared responsibility between immigrants and natives. This notion arguable adheres to the call for more inclusion in the dialogue name. Further, the ambition to identify ‘measures to promote integration and inclusion’ implied an instrumental rather than ideological orientation, without pointing to any particular tension, as opposed to the ambition in Svenljunga, which conveyed an anticipation that the conflict around rural schools would be activated. More specifically, the ambition in Fagersta left limited room for one prominent standpoint in the broader political debate on immigration in Sweden – namely the far right wing claim that the main problem is not qualities of integration measures but rather the volume and/or culture of immigrants received. As recognized by civil servants and politicians following the dialogue, this was a likely reason why the Swedish Democrats declined to participate. Further, it can be speculated that it made the few participants carrying anti-immigration attitudes reluctant to voice those, while also, perhaps partly subliminally, contributing to a more positive outlook on prospects for integration among others. The fact that subgroups were instructed to reach consensus on concrete measures might have contributed to homogenization of views, in line with Dahlgren’s (2009) suggestion above (see also Schkade, Sunstein & Hastie’s 2010), while also subconsciously influencing values underlying these measures, corresponding to the observations in Mugny and Perez (1991).

It should be emphasized that given the effort put into identifying diverse perspectives prior to the dialogue in Fagersta, there are no indications of intentions among civil servants and politicians to subdue tensions. Rather, the apparent incoherence between the normative framing and the ambitious preparations is somewhat puzzling. At the same time, also a dialogue with practice-oriented and normative framing related to integration in a Swedish context should be able to accommodate certain conflict, and it is likely that factors other than those discussed here also influenced how discussions unfolded. Among these, the conscious decision by participants to not include the ‘winners and losers’ perspective in the topics to be addressed was probably significant. When asked about this omission, involved civil servants suggested conflict avoidance as an explanation – a phenomenon since long identified as an obstacle to deliberation (e.g., Himmelroos et al. 2017; Ulbig & Funk 1999).

Concluding Remarks

To reconnect with the purpose of the paper, the reviewed literature as well as the investigated citizen dialogues demonstrate the complexity of influences on deliberators’ attitudes in real-life settings. These influences are challenging to discern for a researcher, and no doubt also for the deliberators themselves. In other words, it is a tall order for them to be aware not only if their attitudes transform during deliberation, but also why and how, as prescribed in theory. While citizen attitudes are subject to manipulation and sub-conscious biases in all realms of society, this is arguably particularly disturbing in contexts where the ideal mechanism for political decisions, if unattainable in its purest form, is autonomous and rational reasoning based on overt persuasion.

At the same time, there is credible evidence in support of the argument that possibilities to curb manipulation and biases are better in deliberation than in many other contexts. When and to what extent these distortions invalidate the legitimacy attributed to communicative rationality thus appears as an empirical question, and increased scrutiny of deliberators’ awareness of attitude transformation may provide parts of the answer. Therefore, it should be added as a component in research evaluating deliberative quality with more sophisticated methods than that applied here. More specifically, while existing empirical studies on different biases and manipulation in deliberation typically deal with single distorting factors in isolation, the literature as summarized in the heuristic model presented here suggests that they are interlinked. Approaches looking into their combined impacts would thus be valuable, albeit no doubt challenging, as they could inform tricky choices that practitioners who design deliberation are faced with, including the delimitation of discourses represented (Dryzek & Niemeyer 2008) and the appropriate level of tension between these (Esterling, Fung & Lee 2015).

Notes

- See also Rostbøll (2005), who argues that consciousness of preference formation is necessary but not sufficient for genuine political freedom, as it may merely allow fine-tuning desires to present conditions without considering possibilities of altering those conditions. ⮭

- This discordance is not addressed in the text, but it can be derived from Tables 1 and 2 (pp. 634 and 636, respectively), and also from the raw data kindly made available by Simon Niemeyer (in litt.). ⮭

- See also Martiny-Huenger et al. (2021) for a discussion of how the framing of policy options in study of deliberation will effect outputs and interpretation of these. ⮭

- The wording of the open-ended question, as translated from Swedish, reads ‘Do you feel that the citizen dialogue has affected your attitudes? If yes, in what ways? If no, why not?’ ⮭

- Pearson’s R correlation coefficients for relationship between attendance and revealed attitude transformations are stronger for attitude switches (0.6 in Fagersta and 0.58 in Svenljunga) than for combined switches and shifts (0.42 in Fagersta and 0.35 in Svenljunga). Presumably, less persuasion is required to accomplish shifts, which therefore happen sooner and therefore correlate less with attendance than switches. ⮭

- p = 0.22 in Fagersta and p = 0.39 in Svenljunga; Mann-Whitney U-tests. ⮭

- This would corroborate Sunstein’s (2009) suggestion that people tend to avoid exposure to viewpoints with which they disagree. ⮭

- I am not aware of other research making use of this correlation to justify or dismiss an assumption of causality, although studies demonstrating cumulative effects on attitudes tracked over dialogue occasions (e.g., Batalha et al. 2019) draw on a somewhat similar logic. ⮭

- Significance of difference between municipalities derived by regressing changes on level of attendance and a dummy separating the two dialogues (p = 0.05). ⮭

- p = 0.71; Mann-Whitney U-test. ⮭

- The fourth respondent stated that she had become more open to the idea of closing rural schools, but did not switch her level of agreement with relevant propositions. ⮭

- Translated from Swedish by author. ⮭

Acknowledegements

I am grateful to Simon Niemeyer for pointing me to useful references and for making available data from his work, and to Martin Westin and two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on earlier drafts.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

1 Achen, C. H., & Bartels, L. M. (2017). Democracy for realists: Why elections do not produce responsive government (Vol. 4). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9781400888740

2 Ackerman, B. (1991). We the people Vol. I: Foundations. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

3 Bartels, L. M. (2003). Democracy with attitudes. In M. B. MacKuen and G. Rabinowitz (Eds.), Electoral democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press (pp 48–82).

4 Bächtiger, A., Dryzek, J., Mansbridge, J., & Warren, M. (Eds.). (2018). The Oxford handbook of deliberative democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198747369.001.0001

5 Barabas, J. (2004). How deliberation affects policy opinions. American Political Science Review, 98(4), 687–701. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055404041425

6 Batalha, L. M., Niemeyer, S., Dryzek, J., & Gastil, J. (2019). Psychological mechanisms of deliberative Transformation: The Role of Group Identity. Journal of Public Deliberation, 15(1), Article 2. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.313

7 Blau, A. (2019). Habermas on rationality: Means, ends and communication. European Journal of Political Theory, 21(2), 1–24. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1474885119867679

8 Bohner, G., Wanke, M., & Michaela, W. (2002). Attitudes and attitude change. Taylor & Francis Group.

9 Boussaguet, L. (2016). Participatory mechanisms as symbolic policy instruments? Comparative European Politics, 14(1), 107–124. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2015.12

10 Casullo, M. (2020). The Body Speaks Before It Even Talks: Deliberation, Populism and Bodily Representation. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 16(1), 27–36. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.380

11 Chambers, S. (1996). Reasonable democracy: Jürgen Habermas and the politics of discourse. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7591/9781501722547

12 Chambers, S. (2009). Rhetoric and the public sphere: Has deliberative democracy abandoned mass democracy? Political Theory, 37(3), 323–50. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0090591709332336

13 Chambers, S. (2018). Human life is group life: Deliberative democracy for realists. Critical Review, 30(1–2), 36–48, DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/08913811.2018.1466852

14 Christman, J. (2009). The politics of persons: Individual autonomy and socio-historical selves. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511635571

15 Cohen, J. (1989). Deliberation and democratic legitimacy. In A. Hamlin and P. Pettit (Eds.), The good polity: Normative analysis of the state. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell (pp. 17–34).

16 Cuppen, E. (2012). Diversity and constructive conflict in stakeholder dialogue: Considerations for design and methods. Policy Sciences, 45(1), 23–46. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-011-9141-7

17 Dahlgren P. (2009). Media and political engagement: Citizens, communication, and democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

18 Dawood, Y. (2013). Second-best deliberative democracy and election law. Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy, 12(4), 401–420. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1089/elj.2013.0202

19 Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. New York: Macmillan.

20 Dryzek, J. (1990). Discursive democracy: Politics, policy and political science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/9781139173810

21 Dryzek, J. S. (2002). Deliberative democracy and beyond: Liberals, critics, contestations. Oxford University Press on Demand. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/019925043X.001.0001

22 Dryzek, J. S. (2005a). Handle with care: The deadly hermeneutics of deliberative instrumentation. Acta Politica, 40(2), 197–211. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500099

23 Dryzek, J. S. (2005b). Deliberative democracy in divided societies: Alternatives to agonism and analgesia. Political Theory, 33(2), 218–242. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X06294109

24 Dryzek, J., & Niemeyer, S. (2008). Discursive representation. American Political Science Review, 102(4), 481–493. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055408080325

25 Dryzek, J. S., Bächtiger, A., Chambers, S., Cohen, J., Druckman, J. N., Felicetti, A., Fishkin, J. S., Farrell, D. M., Fung, A., Gutmann, A., Landemore, H., Mansbridge, J., Marien, S., Neblo, M. A., Niemeyer, S., Setälä, M., Slothuus, R., Suiter, J., Thompson, D., & Warren, M. E. (2019). The crisis of democracy and the science of deliberation. Science, 363(6432), 1144–1146. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw2694

26 Esterling, K. M., Fung, A., & Lee, T. (2015). How much disagreement is good for democratic deliberation? Political Communication, 32(4), 529–551. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2014.969466

27 Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. New York: Harcourt Brace Janovich.

28 Ellul, J. (1962/2021). Propaganda: The formation of men’s attitudes. Vintage.

29 Elster, J. (1983). Sour Grapes. Studies in the Subversion of Rationality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139171694

30 Englund, T. (2000). Rethinking democracy and education: Towards an education of deliberative citizens. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 32(2), 305–313.

31 Feldman, S., & Zaller, J. (1992). The political culture of ambivalence: Ideological responses to the welfare state. American Journal of Political Science, 36(1), 268–307. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/2111433

32 Fishkin, J. (1995). The voice of the people: Public opinion and democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

33 Fishkin, J. (2010). Manipulation and democratic theory. In W. Le Cheminant & J. M Parrish (Eds.), Manipulating democracy: Democratic theory, political psychology, and mass media. London: Routledge. (pp. 31–40). DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9780203854990

34 Fishkin, J. S. (2018). Democracy when the people are thinking: Revitalizing our politics through public deliberation. Oxford Academic, online edn. Retrieved March 29, 2023. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198820291.001.0001

35 Franzén, M., Hertting, N., & Thörn, C. (2016). Stad till salu: entreprenörsurbanismen och det offentliga rummets värde. Gothenburg: Daidalos.

36 Fung, A. (2003). Recipes for public spheres: Eight institutional design choices and their consequences. Journal of Political Philosophy, 11(3), 338–367. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9760.00181

37 Giljam, M., & Jodal, O. (2003). Fem frågetecken för den deliberativa demokratin. In M. Gilljam & J. Hermansson (Eds.). Demokratins mekanismer. Malmö: Liber.

38 Goodin, R. E. (1986). Laundering preferences. In J. Elster & A. Hylland (Eds.), Foundations of social choice theory (pp. 132–148). New York: Cambridge University Press.

39 Goodin, R. E. (2000). Democratic deliberation within. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 29(1), 81–109. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1088-4963.2000.00081.x

40 Goodin, R. E., & Niemeyer, S. J. (2003). When does deliberation begin? Internal reflection versus public discussion in deliberative democracy. Political Studies, 51(4), 627–649. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.0032-3217.2003.00450.x

41 Gutmann, A. (1999). Democratic education. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9781400822911

42 Gutmann, A., & Thompson, D. (1996). Democracy and disagreement. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

43 Habermas, J. (1984). The theory of communicative action (Vol. 1). Boston: Beacon Press.

44 Habermas, J. (1996). Between facts and norms: Contributions to a discourse theory of law and democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/1564.001.0001

45 Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108(4), 814–834. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.4.814

46 He, B., & Warren, M. E. (2011). Authoritarian deliberation: The deliberative turn in Chinese political development. Perspectives on Politics, 9(2), 269–289. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592711000892

47 Hellquist, A., & Westin, M. (2019). On the inevitable bounding of pluralism in ESE—an empirical study of the Swedish Green Flag initiative. Sustainability, 11(7), 2026. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3390/su11072026

48 Hillier, J. (2003). Agonizing over consensus: Why Habermasian ideals cannot be `real’. Planning Theory, 2(1), 37–59. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1473095203002001005

49 Himmelroos, S., & Christensen, H. S. (2014). Deliberation and opinion change: Evidence from a deliberative mini-public in Finland. Scandinavian Political Studies, 37(1), 41–60. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.12013

50 Himmelroos, S., Rapeli, L., & Grönlund, K. (2017). Talking with like-minded people—Equality and efficacy in enclave deliberation. Social Science Journal, 54(2), 148–158. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2016.10.006

51 Huxley, M. (2000). The limits to communicative planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 19(4), 369–377. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X0001900406

52 Imbert, C., Boyer-Kassem, T., Chevrier, V., & Bourjot, C. (2020, December 1). Improving deliberations by reducing misrepresentation effects. Episteme. Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/epi.2018.41

53 Jickling, B., & Wals, A. E. J. (2008). Globalization and environmental education: Looking beyond sustainable development. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 40(1), 1–21. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/00220270701684667

54 Karpowitz, C., & Mendelberg, C. (2018). The political psychology of deliberation. In A. Bächtiger, J. Dryzek, J. Mansbridge & M. Warren (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of deliberative democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (pp. 535–555). DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198747369.013.36

55 Khader, S. J. (2018). Adaptive preferences: Accounting for deflated expectations. In J. Drydyk & L. Keleher (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Development Ethics (pp. 93–100). Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781315626796-11

56 Knight, J., & Johnson, J. (1997). What sort of equality does deliberative democracy require? In J. Bohman & W. Rehg (Eds.), Deliberative democracy: Essays on reason and politics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press (pp. 279–320). DOI: http://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2324.003.0013

57 Kuldas, Ismail, H. N., Hashim, S., & Bakar, Z. A. (2013). Unconscious learning processes: Mental integration of verbal and pictorial instructional materials. SpringerPlus, 2(1), 105–105. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-105

58 Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480–498. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480

59 Lavine, H. G., Johnston, C. D., & Steenbergen, M. R. (2012). The ambivalent partisan: How critical loyalty promotes democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199772759.001.0001

60 Levy, R., Kong, H., Orr, G., & King, J. (Eds.). (2018). The Cambridge handbook of deliberative constitutionalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/9781108289474

61 Lodge, M., & Taber, C. S. (2013). The rationalizing voter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139032490

62 Luskin, R. C., Fishkin, J. S., & Jowell, R. (2002). Considered opinions: Deliberative polling in Britain. British Journal of Political Science, 32(3), 455–487. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123402000194

63 Luskin, R. C., Sood, G., Fishkin, J. S., & Hahn, K. S. (2022). Deliberative distortions? Homogenization, polarization, and domination in small group discussions. British Journal of Political Science, 52(3), 1205–1225. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000168

64 Mackie, G. (2006). Does democratic deliberation change minds? Politics, Philosophy & Economics, 5(3), 279–303. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1470594X06068301

65 Manin, B. (1987). On legitimacy and political deliberation. Political Theory, 15, 338–368. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0090591787015003005

66 Mansbridge, J., Bohman, J., Chambers, S., Christiano, T., Fung, A., Parkinson, J., … & Thompson, D. F. (2012). A systemic approach to deliberative democracy. In Deliberative systems (pp. 1–26). Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139178914.002

67 Mansbridge, J., Bohman, J., Chambers, S., Estlund, D., Føllesdal, A., Fung, A., Lafont, C., Manin, B., & Martí, J. l. (2010). The place of self-interest and the role of power in deliberative democracy. Journal of Political Philosophy, 18(1), 64–100. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9760.2009.00344.x

68 Martiny-Huenger, Bieleke, M., Doerflinger, J., Stephensen, M. B., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2021). Deliberation decreases the likelihood of expressing dominant responses. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 28(1), 139–157. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-020-01795-8

69 McHugh, C., McGann, M., Igou, E. R., & Kinsella, E. L. (2017). Searching for moral dumbfounding: Identifying measurable indicators of moral dumbfounding. Collabra: Psychology, 3(1). DOI: http://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.79

70 Morrissey, L., & Boswell, J. (2020). Finding common ground. European Journal of Political Theory, 22(1), 141–160. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1474885120969920

71 Mouffe, C. (2005). On the political. Londin: Routledge.

72 Mugny, G., & Perez, J. A. (1991). The social psychology of minority influence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

73 Niemeyer, S. (2011). The emancipatory effect of deliberation: Empirical lessons from mini-publics. Politics & Society, 39(1), 103–140. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0032329210395000

74 Niemeyer, S. J. (2004). Deliberation in the wilderness: Displacing symbolic politics. Environmental Politics, 13, 347–72. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/0964401042000209612

75 Niemeyer, S., & Dryzek, J. S. (2007). The ends of deliberation: Meta-consensus and inter-subjective rationality as ideal outcomes. Swiss Political Science Review, 13(4), 497–526. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/j.1662-6370.2007.tb00087.x

76 Niemeyer, S., & Jennstål, J. (2018). Scaling up deliberative effects—Applying lessons of mini-publics. In A. Bächtiger et al. (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of deliberative democracy (pp. 329–347). Oxford: Oxford Academic. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198747369.013.31

77 Niemeyer, S. (2020). Analysing deliberative transformation: A multi-level approach incorporating Q methodology. In S. Elstub & O. Escobar (Eds.), Handbook of democratic innovation and governance (pp. 540–557). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4337/9781786433862.00049

78 Noggle, R. (2022). The ethics of manipulation. In Zalta, E. N. (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2022/entries/ethics-manipulation/

79 OECD. (2020). Innovative citizen participation and new democratic institutions: Catching the deliberative wave. OECD. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1787/339306da-en

80 Owen, D., & Graham, S. (2015). Deliberation, democracy, and the systemic turn. The Journal of Political Philosophy, 23(2), 213–234. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/jopp.12054

81 Polletta, F. (2014). Is participation without power good enough? Introduction to ‘Democracy now: Ethnographies of contemporary participation.’ Sociological Quarterly, 55(3), 453–466. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/tsq.12062

82 Prior, M., & Lupia, A. (2008). Money, time, and political knowledge: Distinguishing quick recall and political learning skills. American Journal of Political Science, 52(1), 169–83. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00306.x

83 Rienstra, B., & Hook, D. (2006). Weakening Habermas: The undoing of communicative rationality. Politikon, 33(3), 313–339. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/02589340601122950

84 Rostbøll, C. F. (2005). Preferences and paternalism on freedom and deliberative democracy. Political Theory, 33(3), 370–396. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0090591704272351

85 SALAR. (2019). Medborgardialog i styrning. Report no. 15. Retrieved from https://skr.se/download/18.583b3b0c17e40e30384496c4/1642431085858/7585-780-0.pdf

86 Schkade, D., Sunstein, C. R., & Hastie, R. (2010). When deliberation produces extremism. Critical Review, 22(2), 227–252. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/08913811.2010.508634

87 Seger, C. A. (1994). Implicit learning. Psychol Bull, 115(2), 163–96. PMID: 8165269. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.115.2.163

88 Sharon. (2019). Populism and democracy: The challenge for deliberative democracy. European Journal of Philosophy, 27(2), 359–376. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/ejop.12400

89 Smets, K., & Isernia, P. (2014). The role of deliberation in attitude change: An empirical assessment of three theoretical mechanisms. European Union Politics, 15(3), 389–409. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1465116514533016

90 Steenbergen, M. R., Bächtiger, A., Spörndli, M., & Steiner, J. (2003). Measuring political deliberation: A discourse quality index. Comparative European Studies, 1(1), 21–48. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.cep.6110002

91 Strandberg, K., Himmelroos, S., & Grönlund, K. (2019). Do discussions in like-minded groups necessarily lead to more extreme opinions? Deliberative democracy and group polarization. International Political Science Review, 40(1), 41–57. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0192512117692136

92 Strassheim, H. (2020). De-biasing democracy. Behavioural public policy and the post-democratic turn. Democratization, 27(3), 461–476. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2019.1663501

93 Sunstein, C. R. (1999). The law of group polarization. John M. Olin Law & Economics Working Paper No. 91. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.199668

94 Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Republic.com 2.0. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

95 Swyngedouw, E. (2018). Promises of the political: insurgent cities in a post-political environment. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10668.001.0001

96 Tewdwr-Jones, M., & Allmendinger, P. (1998). Deconstructing communicative rationality: A critique of Habermasian collaborative planning. Environment and Planning A, 30(11), 1975–1989. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1068/a301975

97 Tooming, U. (2021). Politics of folk psychology: Believing what others believe. THEORIA, 36(3), 361–374. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1387/theoria.21966

98 Ulbig, S. G., & Funk, C. L. (1999). Conflict avoidance and political participation. Political Behavior, 21(3), 265–282. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022087617514

99 Walker, E. T., McQuarrie, M., Lee, C. W., & Calhoun, C. (2015). Rising participation and declining democracy. In C. W. Lee, M. McQuarrie, & E. T. Walker (Eds.), Democratizing inequalities: Dilemmas of the new public participation (pp. 3–24). New York: NYU Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479847273.003.0001

100 Westwood, S. J. (2015). The role of persuasion in deliberative opinion change. Political Communication, 32(4), 509–528. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2015.1017628

101 Wright, G. (2022). Persuasion or co-creation? Social identity threat and the mechanisms of deliberative transformation. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 18(2), 23–34. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.977

102 Young. (1997). Intersecting voices dilemmas of gender, political philosophy, and policy. Princeton University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9780691216355

103 Zajonc, R. B. (1999). One hundred years of rationality assumptions in social psychology. In A. Rodrigues & R V. Levine (Eds.), Reflections on 100 years of experimental social psychology (pp. 200–214). New York: Basic Books.

104 Zhang, K. (2019). Encountering dissimilar views in deliberation: Political knowledge, attitude strength, and opinion change. Political Psychology, 40(2), 315–333. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12514