Introduction

In the past 25 years, we have witnessed the increasing use of democratic innovations such as citizens’ assemblies, deliberative polling, and participatory budgeting, among others, to address the so-called democratic malaise (Newton 2012). Critical to the implementation of ‘governance-driven democratization’ (Warren 2009) are professional participation practitioners who are commissioned to run these processes. By Professional participation practitioners (PPP) we refer to people who provide professional and consulting services in public participation processes in return for payment.1 A vibrant participation industry has emerged in the last 25 years to respond to the demand of commissioning authorities to implement these processes (Barnes et al. 2007; Lee 2015). Against this background, some scholars argue that public participation expertise has become a market commodity that is bought by governments and administrations around the globe (Hendriks & Carson 2008). PPPs act on behalf of a sponsor or client as service providers delivering the good of public participation in an increasingly competitive sector (Bherer et al. 2017b). The outsourcing of the organization and facilitation of public participation endows PPP with a powerful role since they are shaping the actual ‘practice of democracy’ (Cooper & Smith 2012: 4; see also Christensen & Grant 2020). Unlike other government consultants, PPP are processual experts rather than policy experts (Hendriks & Carson 2008). Once commissioned by the client they have considerable influence on the design, institutionalization and operation, and sometimes even evaluation, of participatory processes (Bherer et al. 2017b; Chilvers 2007). Even though PPP hold striking power resources, they are neither legitimated by a political mandate nor held accountable for their actions (Chilvers 2007) – a general problem associated with the proliferation of political consultancy (Hendriks & Carson 2008).

From a normative perspective, especially from a deliberative point of view, this is problematic since such processes should be protected against coercive power (Habermas 1996). However, from a pragmatic point of view, expert facilitation seems inevitable, because “free speech without regulation becomes just noise; democracy without procedure would be in danger of degenerating into a tyranny of the loudest shouter” (Blumler & Coleman 2001: 17–18). Nevertheless, due to their prominent role, PPP needs to be subject to critical analysis. Chilvers (2007:1–2) made this clear by emphasizing that PPP “claim authority in the representation of public views through enacting various “technologies of community” and through offering advice to decision-making institutions on this basis.”

Despite the prominent role PPP play in the field of public participation, scholarly attention has been limited. Only a few studies have shed light on the group of people that is entitled to doctor the perceived crisis of democracy (e.g., Chilvers 2008; Lee 2014; Lewanski & Ravazzi 2017). Accordingly, we know little about the intentions, commitments and attitudes of what we describe in this article as ‘Doctors of Democracy’ (but see: Cooper & Smith 2012; Elstub & Escobar 2019, Section III; Escobar 2017). This study fills this gap by presenting findings from a Q-method study of German PPPs focusing on the practitioners’ self-image and democratic value perceptions. Thus, the main research question reads: Which self-image and democratic values do professional participation practitioners hold?

An empirical answer to this question is relevant in many ways. Firstly, it is important to know which values and perceptions prevail in PPP’s mindsets and consequently shape their day to day work (Cooper & Smith 2012). Secondly, we need to get a clearer picture whether certain attitudes and values are shared among PPPs and which perceptions are distinct. This will also allow us to evaluate whether PPPs can be described as an epistemic community sharing certain beliefs, meanings and values or if they should rather be described as fragmented and divided competitors (Lewanski & Ravazzi 2017). The study uses an innovative approach by applying Q-method, which allows us to create a first typology. Such a typology sets the ground for further research on PPPs who are very likely to affect democratic practices not only nowadays but also in the future. Thirdly, since previous research has mostly analyzed public participation and PPPs against the backdrop of deliberative democratic theory (e.g., Mansbridge et al. 2006; Moore 2012), this study adopts a broader perspective using agonistic, emancipatory, functional, liberal and deliberative value perceptions to map the democratic mindset of PPP.

PPP’s Role in Public Participation Processes and Previous Research

Even though the central role of PPP is often mentioned in participatory literature (e.g., Christensen & Grant 2020; Elstub & Escobar 2017), studies that have analyzed PPP in depth are limited. Some authors have investigated the increasing professionalization and commercialization of public participation. Hendriks and Carson (2008) report a significant increase of enterprises offering participatory services in Australia. They see evidence for professionalization (e.g. formal networks, conferences or professional associations) but they interpret these indicators of professionalization as a development of a ‘community of practice’ than a commercialized and competitive marketplace (Hendriks & Carson 2008: 304). More recently, Christensen and Grant (2020) have discussed the ‘outsourcing of local democracy’ in Australia more critically in terms of commercialization, standardization and capacity. Chilvers’ (2007: 14) study of the UK participatory sector also reports a massive increase of participatory services and an ‘emerging ‘advisory culture.’ He identifies an epistemic community, which is defined to be ‘a network of professionals with recognized expertise and competence in a particular domain and an authoritative claim to policy-relevant knowledge within that domain or issue-area.’ (Chilvers 2007: 3). For Germany, Holtmann (2019) has mapped the vibrant community of participatory service providers. He argues that democratic institutions are increasingly dependent on PPP because they lack the expertise in public participation. Since they do not show much interest to acquire such expertise, the democratic state will cannibalize itself by unlearning how to provide and organize effective participation processes. Market mechanisms may lead to concentration and monopolization where a small number of companies will dominate the participatory market. Such actors will accumulate not just expertise but also sensitive data that are not publicly controlled (Holtmann 2019).

Another strand of literature has focused on the powerful role of PPPs within the participatory process. For example, PPPs are concerned with designing participatory process, such as, defining and framing of the issue under discussion (Chilvers 2007; Landwehr 2014). They advise their clients on selection mechanisms, with subsequent consequences (Fung 2003). They produce and filter information participants should receive by suggesting which experts should be invited or how brochures and webpages should be designed (Hendriks & Carson 2008) and organize participatory events and consult their clients with regard to different methods and formats.

Within the participatory process, PPPs take the role of facilitators exercising influence by performing different moderation technics, enforcing procedural rules or introducing certain perspectives while neglecting others. Several studies have emphasized the leadership role that facilitators take within participatory processes. Moore (2012: 147) makes this very clear when he states that PPP are both ‘part of the structure within which deliberation is supposed to emerge, and self-evidently a participant in the actual discourse itself.’ Landwehr (2014: 77) has described PPP as ‘a kind of personification of discourse rules’ which highlights the important role they play in structuring discussions in participation processes. She further outlines that this role can be interpreted very differently. At a very basic level PPPs ensure procedural rules, for example, keeping a speakers list or make sure that everybody stays on topic. However, they could also support diffident participants, endorse other viewpoints or slow down very active discussants. Further, PPP can endorse particular forms of communication (e.g. rational argumentation), while rejecting others (e.g. emotions) or introduce certain talking points (Landwehr 2014). Ultimately, PPP can take an advocacy position by presenting potential reasons and viewpoints of absent groups (Landwehr 2014). A study of 16 different organizations dealing with the planning and designing of public deliberation processes by Ryfe (2002) reveals different viewpoints on inclusiveness and group cohesion, methods applied within the process as well as with regard to target groups. They also vary in terms of preferring rather rational or relational (e.g. including narratives and emotions) modes of deliberation (Ryfe 2002). Mansbridge and colleagues (2006) analyzed facilitators with regard to the question what they consider a good deliberation process. Findings suggest that facilitators do not adhere to strict normative standards but rather try to take the deliberators’ perspective. Participants’ satisfaction and group productivity are considered equally important. Emotional interactions and rational reasoning are similarly vital, while the standard of common good orientation is relaxed to the value of common ground where deliberation could start from. A widely perceived obstacle of good deliberation is the multi-faceted issue of inequality, which has to be considered but can rarely been overcome completely (Mansbridge et al. 2006).

Finally, PPPs serve as aggregators which means that they are left with the task to synthesize the public input and draw final conclusions (Chilvers 2007). Throughout the process they have to sum up results, define issues and open up new but also close topics under discussion. At the same time, they have to identify common ground and areas of disagreement or conflict (Landwehr 2014).

Few studies have analyzed PPPs’ attitudes and values perceptions in detail. Bherer and colleagues (2017b) studied PPPs in Canada with a focus on impartiality in the context of commercialization. They found that PPPs vary in their evaluation of the sponsors’ influence and the impact of the topic under discussion. Findings indicate that PPPs develop different strategies to cope with the issue of impartiality and that the discussed topic affects services differently. Thus, PPPs cannot be seen as a homogenous group (Bherer et al. 2017b). Lewanski and Ravazzi (2017) conclude that the practitioners’ culture plays a key role for the process design and map a divided participatory culture in Italy. Even though PPP share basic ideas on public participation such as improving democracy, impartiality, transparency and the need for early problem definition, the authors identify strong disagreement with regard to the desirable outcomes of public participation. While some focus on community building and education, others are concerned with effective policy making and legitimacy. This division in desirable outcome perceptions translates into a different usage of tools and techniques.

Cooper and Smith’s (2012) study suggests that PPPs reflect democratic principles in their daily work. They put a strong focus on equality and deliberation. PPP highlight several constraints to a more effective institutionalization of public participation, for example, that clients do not fully understand demands of public participation. Institutional and cultural persistence within public administration are another obstacle perceived. In addition to that, PPPs raise concerns with regard to the commercialization of the field that can lead to a race to the bottom where the cheapest service wins the contract (Cooper & Smith 2012).

In sum, previous research suggests that PPPs are powerful actors in an increasingly commercialized and professionalized participation sector (Cooper & Smith 2012; Hendriks & Carson 2008). Within this environment the norms of neutrality and impartiality are contested. While regarded as normatively important (Chilvers 2017; Lewanski & Ravazzi 2017), findings indicate that the practical interpretation varies across PPP (Bherer et al. 2017b). This is closely related to the question who is perceived to be the actual client. While some PPP primarily want to satisfy citizens’ needs (Mansbridge et al. 2006), others privilege the sponsors’ expectation (Bherer et al. 2017b) or democracy itself (Cooper & Smith 2012). PPP consider democratic values such as equality and rational reasoning as normative guidelines in their daily work but also give floor to emotions and personal stories (Mansbridge et al. 2006; Ryfe 2002). However, PPP’s daily business is not rigidly structured by normative principles, but rather influenced by their own knowledge, skills and experience gained on the job (Chilvers 2017; Cooper & Smith 2012). With regard to democratic principles, previous research has restricted its focus mostly on deliberative norms, thus neglecting other democratic perspectives, which this study wants to overcome.

Method and Design

Previous research on PPPs has usually applied qualitative methods, mostly semi structured interviews (e.g., Bherer 2017b; Chilvers 2017). This study aims to broaden the methodological scope by using Q-method to gain more knowledge on practitioners’ self-images and democratic values. Q-method was firstly introduced by William Stephenson (1953) to understand the phenomenological world of individuals ‘without sacrificing the power of statistical analysis’ (Stephen 1985: 193). This chapter will outline the methodological approach in detail.

Construction of the Q-Sample

The starting point of any Q-methodological study is the so-called Q-Sample (or Q-set). The Q-sample usually involves 40–80 statements which should represent a wide range of possible characteristics of the domain under study (Watts & Stenner 2005). The final Q-sample, later sorted by the participants, arises from the concourse (from the Latin concursus, meaning ‘a running together’, as when ideas condense in a thought) (Brown 1993). The concourse can be understood as the full set of possible opinions, attitudes and meanings attached to certain subject or as Maier (2021: 2) puts it: ‘a universe of statements that captures different aspects and understandings of an issue.’ The main goal is to extract a well-rounded set of items out of the concourse which provides a fair representation of dimensions studied (Stephen 1985).

For the purpose of this study, we initially extracted 134 statements representing the concourse of the study. After internal considerations and discussions with experts, this corpus of statements was condensed to a final Q-sample of 48 statements representing all dimensions relevant to this study (see Tables 1 & 2). The procedure of conducting the Q-sample followed a hybrid approach combining elements of naturalistic and quasi-naturalistic sampling. While naturalistic sampled statements are retrieved from the everyday life contexts of potential participants, quasi-naturalistic sampled statements where extracted from academic literature but still have a nexus to the participants’ daily work context. In our case we extracted statements from previous research and five different democracy concepts. For example, we formulated three statements that targeted different Customer Perceptions (Sponsor, Citizens, Democracy), two statements that each represent the Clients respective Citizens’ Image or the impact of Economic Constraints. Drawing on previous research, we included statements with regard to PPP’s Impact Perception, Impartiality and Neutrality. Table 1 summarizes this first set of statements.

List of Statements (1–23) and Dimensions used (Median (M) and Standard Deviation (SD); N = 40).

| No. | Dimension | Statement | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic Perceptions | ||||

| 1 | Customer Perception | My goal is to satisfy the client | 0.0 | 2.4 |

| 2 | Customer Perception | My goal is to give people a voice within the political process | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| 3 | Customer Perception | My goal is to make democracy a little bit better | 2.0 | 2.1 |

| 4 | Clients’ image | Usually, I have to explain to my clients how public participation processes succeed | 1.7 | 2.0 |

| 5 | Clients’ image | There are usually conflicts between me and the client | –3.2 | 1.6 |

| 6 | Citizens’ image | My first priority are the citizens’ needs | –0.8 | 1.6 |

| 7 | Citizens’ image | Usually, I have to explain to citizens what is possible through a public participation process | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| 8 | Competence Perception | As an expert for public participation I am more competent to provide participatory services than public authorities | 1.0 | 2.1 |

| 9 | Competence Perception | It would be better if the provision of public participation would be in states’ hand | –3.1 | 1.6 |

| 10 | Economic constraints | To receive contracts in the future, it is okay to value the sponsors’ satisfaction more | –1.7 | 2.0 |

| 11 | Economic constraints | Financial restrictions make it difficult to always stick to my principles | –1.3 | 2.4 |

| 12 | Economic constraints | With more financial resources I would be able to provide better participation processes | 0.8 | 2.1 |

| 13 | Impact Perception | I am aware of the fact that design choices made by me affect outcomes significantly | 0.6 | 1.9 |

| 14 | Impact Perception | The design of the process does not have a huge impact on the final outcomes | –2.9 | 1.9 |

| 15 | Impartiality | I should never take the clients’ nor the citizens’ position during a participatory process | 0.7 | 2.4 |

| 16 | Impartiality | As participatory practitioner I can never be completely neutral | –0.3 | 2.4 |

| 17 | Project Perception | I prefer not to work on projects that contradict my political values | –0.4 | 2.5 |

| 18 | Project Perception | Whether I like a project or not, does not affect my work | –0.9 | 2.3 |

| 19 | Project Perception | I do not have any say on the projects I am working on | –2.4 | 2.0 |

| 20 | Responsibility | At the end of the day the client is responsible for the political outcomes | 1.0 | 2.6 |

| 21 | Responsibility | I am also responsible for the final decisions made after a participation process | –2.9 | 1,7 |

| 22 | Neutrality | Within the participatory process I am deeply engaged and actively mediate between participants | –0.9 | 12.0 |

| 23 | Neutrality | At best, participants should not recognize me during the participatory process | –1.4 | 1.9 |

List of Statements (24–48) and Dimensions used (Median (M) and Standard Deviation (SD); N = 40).

| No. | Dimension | Statement | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic Values | ||||

| 24 | Liberal | I organize public participation process in order to include all opinions in the decision-making process | 1.1 | 2.0 |

| 29 | Liberal | My goal is to ensure that all opinions at stake have had a chance to be heard | 0.3 | 1.9 |

| 34 | Liberal | Within participation processes citizens usually behave rationally and reasonably | –3.1 | 2.0 |

| 35 | Liberal | Everybody is able to defend one’s own interests | –1.1 | 2.5 |

| 36 | Liberal | The best possible outcome of a participatory process is a win-win situation | 0.8 | 2.6 |

| 25 | Functional | I organize public participation because citizens possess relevant knowledge | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| 30 | Functional | My goal is to incorporate as much knowledge as possible to develop the best solution | 1.4 | 2.2 |

| 37 | Functional | To make all relevant information enter the process, I have to ensure that all knowledge carriers are included | 1.6 | 1.9 |

| 38 | Functional | My primary focus is to include civil society actors | –1.7 | 2.2 |

| 39 | Functional | My primary focus is to include experts | –1.0 | 2.0 |

| 26 | Deliberative | I organize public participation processes to ensure that decisions are made against the backdrop of a rational, fair, transparent process | 3.0 | 1,7 |

| 31 | Deliberative | My goal is that at the end of a participatory process consensus and mutual understanding emerge | 1.5 | 2.1 |

| 40 | Deliberative | For me, a successful process is achieved when the best argument succeeds | –1.0 | 2.0 |

| 41 | Deliberative | For me, a success is when people have changed their minds or at least learn about other positions throughout the process | 1.0 | 2.5 |

| 42 | Deliberative | For me, a successful process is achieved when everybody can agree on the final outcome | 0.1 | 2.8 |

| 27 | Emancipatory | I organize public participation processes to give marginalized groups a voice in decision making processes | 0.3 | 2.0 |

| 32 | Emancipatory | My goal is that citizens who may have not been enabled at the beginning of the process have learned something about how policy making works | 1.0 | 1.8 |

| 43 | Emancipatory | For me, a successful process is given when traditional power structures have been recognized and cracked | –1.6 | 1.6 |

| 44 | Emancipatory | It is part of my job to give minorities and marginalized groups a voice | 0.5 | 1.6 |

| 45 | Emancipatory | My long-term goal is to raise citizens’ political competences – particularly for individuals who are overlooked by politics | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| 28 | Agonistic | I organize public participation processes in order to make conflictual positions salient | 0.9 | 2.0 |

| 33 | Agonistic | My goal is to make conflictual interests salient even though they cannot be pacified | 1.4 | 1.9 |

| 46 | Agonistic | My job is to provide a platform for strongly different interests | –1.0 | 2.3 |

| 47 | Agonistic | I think emotions and passions are central elements of public participation processes | 1.5 | 2.1 |

| 48 | Agonistic | It is my job to reveal conflicts and dissent | 1.3 | 2.2 |

In order to map democratic values, we formulated statements that represent basic assumptions from five different democratic traditions. We will briefly discuss each tradition without going into much detail, starting with liberal models that put a strong focus on individual rights (Mill 1971). Consequently, citizens are believed to be able to take care of their own business. The main goal of participation is to provide everybody whit a fair chance to articulate personal preferences that political elites can monitor. The best possible outcome is a win-win situation that could, but don’t have to, emerge from the market of ideas and preferences (Renn, 2008).

The functional conceptions of democracy emerge from the idea that complex societies are characterized by functional differentiation (Parsons 1952). In this perspective, participation is ‘necessary in order to meet complex functions of society that need input (knowledge and values) from different constituencies’ (Renn 2008: 295). Thus, the main goal is to incorporate as much expertise from different background in of decision-making processes.

In contrast to the both previous traditions, deliberative theories put a strong focus on discourses which is characterized as a respectful exchange of reasons among equal participants (Habermas 1996). Thus, participation is envisioned as a demanding communication process that needs to follow certain rules and, ideally, is culminating in consensus among participants. In addition to that, deliberative theory assume that people can change their minds and develop certain democratically desirable skills (Mutz, 2008).

The emancipatory tradition shares the idea that participants undergo some sort of transformation during the participatory process. However, they primary goal is to empower marginalized groups. Thus, participation is about uncovering and cracking existing power structures by giving less privileged groups the opportunity to have their voices heard. However, participation does not only provide the means to empower certain groups but also to educate them in democratic affairs (Renn 2008: 299–300).

The final tradition used to qualify PPP democratic attitudes is the agonistic model of democracy which emphasizes the role of conflicts, hegemony and passions within political processes (Mouffe 2005). In this conception, participation makes conflictual positions salient and provides a venue where dissent can be articulated in passioned ways. In contrast to deliberative ideas, however, agonism does not aim to solve or pacify those conflicts. Table 2 summarize all statements that aim to represent the five different models of democracy.

Recruitment of Participants

This study seeks to shed light on the subjective attitudes and democratic values of PPPs in Germany. Public participation has become increasingly relevant in the last three decades in Germany (Klages & Vetter 2013). Due to the structure of Germanies political system, public participation is mostly exercised at the local level and a significant share of municipalities already have experimented with local participation processes (Rottinghaus et al. 2020; Schöttle et al. 2016). In order to serve these participatory demands, a vibrant and relatively young community of professional participation companies (mostly founded in the early 2000s) has emerged in Germany (Holtmann 2019). According to Holtmann (2019), administrations and political institutions have hesitated to build up own participatory skills and competences. Thus, even though we can see that administrations have created certain administrative and personnel structures for the purpose of public participation in recent years (Rottinghaus et al. 2020), PPP are usually consulted when it comes to public participation processes in Germany. Against this backdrop, administrations are more or less dependent upon the external expertise of PPP (Holtmann 2019).

Even though there are (probably) more than 40 companies that compete on the national participatory market, most players in the field know each other personally and even cooperate in certain projects. Germany’s participation industry, however, varies in terms of background, business model and scope. Some of them are organized as (more or less) non-profit foundations (e.g. Bertelsmann-Stiftung; Liquid Democracy e.V., Stiftung Mitarbeit), others have a clear commercial profile by selling participation as their key product (e.g., Navos, Polidia, Zebralog). Some companies are academic spin-offs with a respective scientific profile (e.g., Nexus Institute, wer-denkt-was), while others have a consultancy portfolio where participation marks only one of many services (e.g. ifok).

The sampling of German PPP is challenging since the basic population is not easy to detect. There is no register of German PPPs, and parameters of what counts as PPPs are not immediately apparent given the diversity of their organizational profiles. Drawing on our knowledge of the field, we compiled a list of companies and organizations which have strong expertise with regard to public participation. This list did not include in-house participation professionals or street-level bureaucrats that are responsible for public participation processes from the administrative perspective, but only PPP from the private sector who are potentially subcontractors. This first list contained 32 companies and organizations ranging from small start-up enterprises (1–6 employees) up to bigger communication consultancies with more than 40 employees. The list was sent to two experienced participation practitioners to check for integrity. The experts affirmed our selection, added three companies for us to contact, and made several changes with regard to contact persons for the study. Thus, we ended up with a final list of 35 companies and 68 identifiable contact persons.

We reached the contact persons by email between August and October 2020 and were asked if they would like to participate in the Q-study. Potential participants could easily access the study via a weblink that redirected participants to the Q-Method Software. The offered phone support was used by only two participants which indicates a fair usability of the tool. The Q-Method Software is a charged platform-based tool that allows researchers to set up, conduct and analyze Q-studies online (Lutfallah & Buchanan 2019). It includes a user-friendly dashboard and statistical presets that allow to run automated data analyses. The dashboard provided the information that 62 persons clicked on the weblink, while 40 have completed the study, which took them an average time of 24 minutes (range:16–41 min.). Our final sample consisted of 40 PPP from 27 different companies. Thirty of them provided us with some personal information via a short survey. Those answers indicate that our sample can be described as rather experienced (73% >6 years job experience), specialized in public participation (67% describe participation to be their key business) and slightly male (55% male/45% female).

Q-Sort Procedure

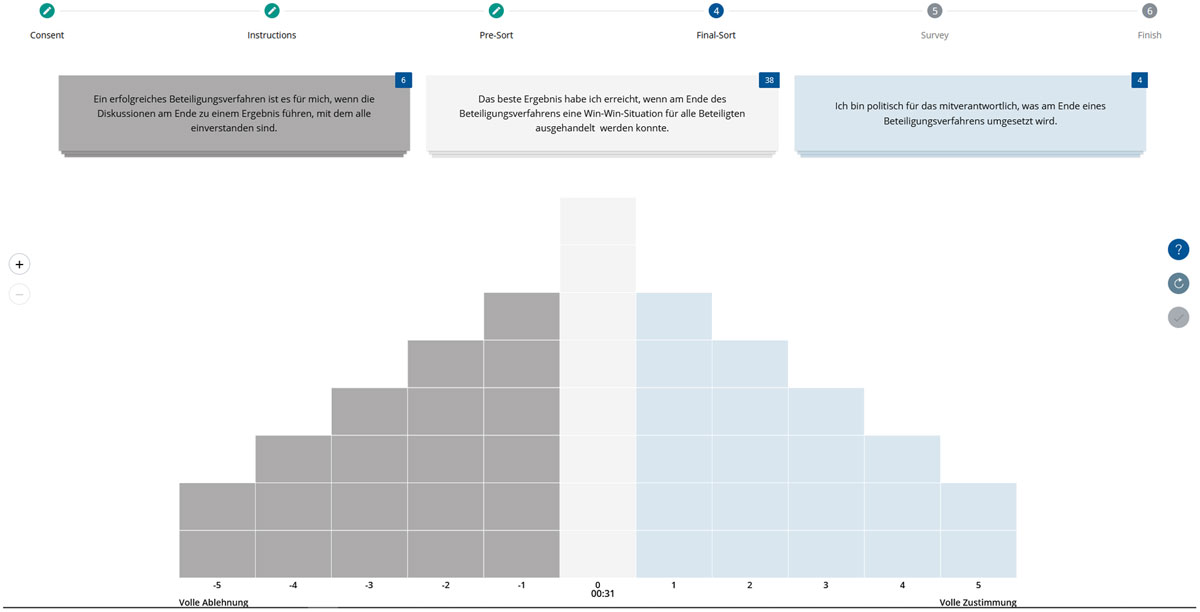

The next crucial step in Q-methodology research is the Q-sort where participants are asked to rank a total of 48 statements (Tables 1 & 2). The sorting followed a two-step procedure. In the first step, all participants were asked to sort all statements in three categories: agree, neutral, disagree. This first step left the participating PPPs with three piles of statements which they should sort into a grid, set up like a normal distribution. In our case the normal distribution was linked to a scale ranging from completely agree (+5) to completely disagree (–5). To avoid floor and ceiling effects that can be found in other Likert-type studies, the ‘number of rows can vary based on how many cells the researcher chooses to add to each column.’ (Lutfallah & Buchanan 2019: 417) Thus, the number of cells exactly matches the number of statements to be sorted (Figure 1).

This scale forced all 40 PPPs to reflect on their preferences and thus make a fine-grained distinction between the different statements. Since participants had to weigh the statements in relation to each other, every Q-sort represents an individual map of subjective meanings (Lutfallah & Buchanan 2019).

Data analysis

The Q-sorts by 40 PPPs were analyzed through correlation and explorative factor analyses. The unit of analysis is the single Q-sort. The used tool provided several integrated functions so that partial automation could be used. In a first step we created a correlation matrix of all the participants’ individual Q-sorts. These correlations indicate which Q-sorts tend to be similar. Similar Q-sorts constitute a cluster of subjectivity also known as factors. The Q-correlations provide the starting point for the factor analysis which reveals a typical Q-sort for each factor. Thus, a factor arises through highly correlating Q-sorts. Drawing on the correlation matrix, the tool grouped the Q-Sorts automatically into seven factors. Varimax rotation was chosen to increase declared variance. In order to be extracted, a factor must have had an eigenvalue greater than one and at least two loading Q-sorts (Watts & Stenner 2005). Considering these two statistical conditions, we ended up with five distinct factors (A-E), which explain 59% of the variance (SD = 2.585; Var(X) = 6.682). Overall, 28 of the 40 Q-Sorts loaded on one of the five factors (2). Each factor represents a typical arrangement of the Q-sample statements that are most representative for the factor. They serve as bedrock for the typology to be discussed in the next section.

Results

The main aim of this research is to shed light on German PPP’s self-image and democratic value perception related to public participation. In this section, we firstly present some descriptive findings introducing the most shared perceptions. Secondly, we introduce a typology in order to carve out the differences among PPP.

Shared perceptions among PPP

The data provided by 40 PPP who finished the Q-Sort gave us information on widely shared attitudes and democratic values which we summarize under the term ‘perception’. In order to identify shared perceptions, we calculated the average agreement towards all 48 statements (–5 – +5). The overall ratings are mirrored in Tables 1 and 2 above. For the purpose of this section, we limit our focus to the five most supported and the five most rejected statements.

The most agreed statement suggests that PPP share the deliberative ideal that public participation processes are organized to ensure ‘that decisions are made against the backdrop of a rational, fair and transparent process’ (statement 26; M = 3.0; SD = 1.7). They further pursue the goal ‘to make democracy a little bit better’ (statement 3; M = 2.0; SD = 2.1) through public participation, which indicates that democracy is the main ‘customer’ for most PPP. We also see a fair amount of support for the statement ‘my long-term goal is to raise citizens’ political competences’ (statement 45; M = 1.9; SD = 1.8), which seems to support the overall perception shared by PPP to foster democracy. However, results also show that PPP are ‘educative’ in the sense that they have to explain citizens (statement 7; M = 1.8; SD = 1.8) and clients (statement 4; M = 1.7; SD = 2.1) what public participation is about.

Focusing on the most rejected statements reveals that PPP widely perceive the relationship to clients as harmonious. Thus, the statement that ‘there are usually conflicts between me and the client’ is strongly rejected (statement 5; M = –3.2; SD = 1.6). Less surprisingly, PPPs also oppose the statement that ‘it would be better if the provision of public participation would be in states’ hand’ (statement 9; M = –3.1; SD = 1.6). We further found a critical assessment of citizens. Most PPPs unanimously reject the statement that ‘within participation processes citizens usually behave rationally and reasonably’ (statement 34; M = –3.1; SD = 1.9). With regard to the power of process designing, our analysis suggests that PPP perceive their impact through design. Thus, they reject the statement that ‘the design of the process does not have a huge impact on the final outcomes’ strongly (statement 14; M = –2.9; SD = 1.9). Even though PPP agree to have significant impact on the final results of participatory processes, they unanimously reject to be (partly) held accountable for final decisions. The statement ‘I am also responsible for the final decisions made after a participation process’ is strongly opposed (statement 21; M = 2.9; SD = 1.7).

Finally, regarding PPPs’ viewpoints on different conceptions of democracy the descriptive analysis suggests a prevalence of deliberative (M = 1.8) and agonistic (M = 1.2) perceptions while functional statements are mostly rejected (M = –0.4). Statements mirroring liberal (M = 0.3) and emancipatory (M = 0.2) ideas of democracy are averagely supported but significantly less than agonistic and deliberative statements (see Table A: Appendix).

Different PPP Types

While the analysis of all 40 finished Q-sorts provided us with valuable insights on the shared perceptions of sampled PPP, we now want to shed light on the differences. For this purpose, we run an explorative factor analysis (see method section). From all 40 participants, 28 loaded on one of the five factors. The following discussion of types draws on these 28 PPPs.

The factor (A) can be described as the Empowering Democracy Enhancer (N = 7). The main aim of this type is to enhance democracy (statement 3, fs = 5) which is also mirrored by the strong will to foster citizens’ democratic skills (statement 45, fs = 5). PPP loading on this factor aim to give voice to marginalized groups (statement 2, fs = 4) and provide them with political education (statement 27, fs = 3). Accordingly, this type strongly rejects the integration of organized interests (statement 38, fs = –5) or experts (statement 39, fs = –4). The empowering understanding of democracy marks the distinguishing dimension compared to the other types. Further, this type identifies with values retrieved from deliberative democracy such as a strong commitment to design a rational, fair and transparent process (statement 26, fs = 4) and the goal to achieve consensus (statement 31, fs = 3). This type perceives the citizen (statement 2, fs = 4) to be his/her main client while the sponsor is disregarded (statement 1, fs = 0). Another distinguishing aspect is the important role of the issue under discussion. PPP in this type report a strong issue impact on their work (statement 18, fs = –4) as well as the freedom to choose the projects they want to work on (statement 19, fs = –3). However, this type also perceives that financial restrictions affect their work significantly (statement 11, fs = 2; statement 12, fs = 3).

Factor B was labeled the Mediating Facilitator. Most of the PPPs in our sample are loading on this factor (N = 10). Even though other types also regard the organization of a rational, fair, transparent process as a key objective, this type emphasizes this goal most significantly (statement 26, fs = 5). PPP in this type also emphasize their neutral role within the process (statement 16, fs = –3; statement 15, fs = 4). This type puts a strong focus on consensus as the final goal of participatory processes (statement 42, fs = 5; statement 31, fs = 4). In addition to that, this type also wants to reveal conflicts and dissent among participants (statement 48, fs = 4; statement 33, fs = 3). Furthermore, this type strongly agrees to the liberal statement that participatory processes should integrate all public positions into decision making processes (statement 24, fs = 4). In contrast to all other types, this type reflects multiple democratic values which are higher evaluated than in the other types. Conflicts with the client do not play a role for PPP grouped under this type (statement 5, fs = –5). In contrast to factor A, PPP of this type do not see financial aspects affecting their work (statement 11; fs = –4). Similar to most other types, PPP hold a very pessimistic view of citizens’ capability to be rational in participatory processes (statement 34, fs = –4) and reject any sort of responsibility for political outcomes (statement 21, fs = –4).

Factor C could be labeled the Enlightening Contractor (N = 4). The type of label is caused by its strong focus on the client’s satisfaction (statement 1, fs = 4) and citizen’s learnings (statement 45, fs = 4) and its aim to teach both, client and participants the opportunities of public participation processes (statement 7, fs = 5; statement 4, fs = 5). This educative attitude towards the client and the citizen is the distinguishing feature to all other types identified. However, the aim to educate people seems to be inspired by a very strong negative attitude towards citizens’ capability to represent their own interest (statement 35, fs = –5) or to be a rational actor in participatory processes (statement 34 = –5). This kind of ‘arrogant’ attitude is also supported by their strong belief that they, that is PPP, are most competent to conduct participatory processes (statement 8, fs = 4) and the perception that they strongly influence final outcomes (statement 13, fs = 4). Neutrality does not play an important role for this type: PPP in this category agree that it is hard to be neutral within the participatory process (statement 16, fs = 4) and do not aim to reach consensus among participants (statement 42, fs = –4). Both statements demarcate this type from factor B. Individuals in this type also reject the aim to actively mediate between participants (statement 22, fs = –3). In contrast to Type A, this type seems very dispassionately with regard to the project they work on (statement 17, fs = 0). With regard to democratic value perceptions this type does not show significant support for one particular conception. However, there is a slight tendency for agonistic and functional values.

The fourth factor (D) gathers the Democratic Teacher (N = 4). This type’s main goal is to enhance democracy (statement 3, fs = 5), integrate as many perspectives as possible into the participatory process (statement 25, fs = 4) and foster democratic skills of participants (statement 45, fs = 3). All PPPs in this type emphasize their neutral role within the process (statement 15, fs = 5) which demarcates this type from all other types. PPP in this type want participants to learn more about other perspectives and change their minds in the light of other participants’ viewpoints (statement 41; fs = 4). Accordingly, compared to other types, this type has a relatively positive perception of citizens’ rational capabilities (statement 34, fs = –1). With regard to democratic values this type emphasizes functional (statement 25, fs = 4; statement 37, fs = 4) and deliberative attitudes (statement 41, fs = 4; statement 26, fs = 3). The client’s satisfaction (statement 1, fs = –3; statement 10, fs = –4) as well as financial aspects (statement 11, fs = –4) do not play an important role. While this type reports to have significant impact on the final outcomes of a participation process (statement 14, fs = –5), they equally reject any sort of responsibility for political outcomes informed by the process they conducted (statement 21, fs = –5).

The final factor (E) our analysis revealed can be named Agonistic Mediator (N = 3). The main goal of this type is to reveal conflict and dissent (statement 28, fs = 4; Statement 33, fs = 5; Statement 48, fs =3). Citizens should learn about other viewpoints and reevaluate personal views (statement 41, fs = 5) while the integration of marginalized groups is important (statement 44, fs = 3). In contrast to all the other factors, PPP of this type strongly reject win-win situations (statement 36, fs = –4) and consensus (statement 42, fs = –4) as an outcome of participation processes. Another distinguishing aspect is the overall low assessments of the individual impact on the final outcomes of participation processes (statement 14, fs = 2). Thus, with regard to democratic values, agonistic and some deliberative statements are salient.

Discussion

The main aim of this research was to explore the diversity of German PPPs’ self-image and democratic values. Throughout this paper we have outlined the important role PPP play when it comes to public participation processes. Since additional participatory opportunities are usually introduced in order to cure ailing democracies (e.g., Newton 2012; Warren 2009), we argued that scholarship should monitor the ‘doctors’ of this therapy with critical attentiveness because, metaphorically, PPPs conduct surgery on the open heart of democracy. In this discussion we want to highlight some findings, discuss limitations and point towards further research options.

Against the backdrop of increasing professionalization and commercialization, previous research has prompted the question to whom PPPs feel obligated to clients, citizens or democracy (Bherer et al. 2017b). Our results indicate a clear focus on democracy itself. The statements on the sponsors’ needs are evaluated in a rather neutral manner, while giving voice to citizens in political processes is more important to German PPP. However, improving democracy by providing rational, fair and transparent participation processes seems the main goal to them. Our findings also indicate that the relationship between PPP and sponsors are both harmonious and asynchronous. While conflicts seldomly accrue, PPP report that they often have to explain to clients what public participation is about. Less surprisingly, PPP perceive themselves as specialists or experts of public participation with a strong advantage towards public authorities, under the impression that they have more expertise or competent compared to their bureaucratic counterparts. These findings bolster the argument that public authorities are dependent on external expertise which is neither challenged nor contested (Chilvers 2007; Holtmann 2019).

While most PPP in our sample aim to give people a voice in policy processes and provide political education, our findings also reflect a fairly pessimistic perception of citizens. According to our data, citizens need to be disabused with regard to public participation and do not act rationally within the process. Further, we found a rather pessimistic evaluation with regard to the liberal position whether everybody is able to defend one’s own interests. This pessimistic image of the citizen could be explained by PPP’s regular exposure to ‘usual suspects’ or so called ‘professional citizens’ (Berufsbürger) who are characterized by frequent participation, strong opinions and rigid outcome perceptions (Cooper & Smith 2012).

The general commercialization of the participation sector can be considered to be empirically evident (Bherer et al. 2017b; Lee 2015). Thus, previous studies have raised concerns whether increasing commercialization could harm participatory ideals. For example, Hendriks and Carson (2008: 309) made the claim that ‘if the motivations for deepening democracy are fully replaced by business imperatives and competition, then the deliberative project would be severely undermined.’ Similarly, Lewanski and Ravazzi (2017: 21) have argued that commercialization could foster ‘design choices that are driven more by the instrumental aim of beating competitors than by the substantive aim of designing “good” process.’ Those concerns are not supported by our findings. Economic imperatives do not seem play a crucial role for German PPP. Most PPP agree that more budget would enable them to provide better public participation processes and that they would not privilege a client in order to receive future contracts. Even though the Empowering Democracy Enhancer admits that it is sometimes financial constraints make it difficult to always follow one’s own principles, surveyed PPP reject this statement overall. In addition to that, our results indicate that the satisfaction of clients’ needs are not the top priority of PPP except for the four individuals who constitute the type of the Enlightening Contractor. However, given that PPPs may form an ‘epistemic community’ (Chilvers, 2007) this could be a necessary part of their shared habitus, and an important legitimating ideology, to de-link economic imperatives from their work. Thus, further research should have a deeper look in that comparing private sector PPP attitudes with those of other groups doing participatory work such as public sector participation workers or activist participation practitioners.

Previous research has suggested that PPP either hold instrumental views on public participation, focusing on effective policy making and legitimacy, or ethical views, focusing on community building and education (Lewanski & Ravazzi 2017; Bherer & Breux 2012). Interpretation of respective statements in our Q-study across the different factors supports this hypothesis. Thus, while the Empowering Democracy Enhancer and the Agonistic Mediator hold a rather ethical view, the three other types are characterized by instrumental perceptions. However, the complete sample slightly leans towards ethical perceptions.

Finally, our data affirms the processual influence that previous research has attributed PPPs (Bherer et al. 2017b; Chilvers 2007; Landwehr 2014). We found that PPPs thoroughly perceive their influential role within the process. They are well aware of the fact that certain design decisions or moderation techniques have significant influence on the outcomes of participatory processes. Further, findings indicate that they are fairly autonomous to decide which projects they want to work on. Despite the perceived impact and the opportunity to choose the topics to work on, PPP do not perceive any sort of responsibility nor accountability for the outcomes and potential consequences associated with their work. These findings may foster further reflections and debates about the need for a code of conduct or some forms of regulations within the participatory industry (Cooper & Smith 2012). By all means, it should prompt further normative and empirical investigations which are beyond the scope of this paper.

It goes without saying that this study is subject to several limitations. While both sociological role theory (e.g., Linton 1936) and previous research (e.g., Lewanski & Ravazzi 2017) suggest that self-images and values shape the way PPP design and conduct public participation initiatives, the descriptive approach of this study allows no inferences on how these attitudes actually translate into participatory processes and which effects are caused by them with regard to its outcomes. The suggested typology can serve as a fruitful starting point to further research analyzing how certain types of PPP shape participatory processes and respective outcomes. Another limitation arises from the methodological design. While the Q-method is useful in order to research latent and complex concepts and deepen the understanding of underexplored research objects, the generalizability of the findings is limited. Thus, findings presented in this study have to be interpreted with caution. However, the sampling procedure that captured most professional agencies for public participation services in Germany and the Q-sorts by 40 PPPs allow for a first assessment and provide a fruitful starting point for further quantitative and comparative research.

Despite these limitations, the study contributes to a nuanced understanding of a key actor in the process of public participation by conducting one of the first Q-method studies in the field and – to the best of our knowledge – the first for German PPP. While previous research has already shed light on PPP professional attitudes, their democratic attitudes have mainly been researched against the backdrop of deliberative norms, thus neglecting other democratic perspectives. This study has broadened the democratic perspective by introducing five different democratic traditions which can provide a fruitful starting point for further research on PPP democratic belief systems. Same might hold true for the introduced typology, that can set the ground for further research on an elitist group of people who shape participatory spaces not only today but also in the future.

Notes

- We borrow the term Professional Participation Practitioners (PPP) from Cooper and Smith (2012), who use it as an umbrella term covering descriptions such as ‘facilitators’ (Moore 2012), ‘public participation professionals’ (Bherer et al. 2017a), ‘participatory process experts’ (Chilvers 2008), ‘public engagements practitioners’ (Lee 2015) or ‘deliberative organizers’ (Hendriks & Carson 2008). ⮭

Appendix 1

Democratic value perceptions by surveyed PPP (drawing on an index of three key dimensions).

| Democratic Concept/Statement | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Liberal | ||

| I organize public participation processes in order to include all opinions in the decision-making process | 1.1 | 2.0 |

| Everybody is able to defend one’s own interests | –1.1 | 2.5 |

| The best possible outcome of a participatory process is a win-win situation | 0.8 | 2.6 |

| 0.3 | ||

| Functional | ||

| My goal is to incorporate as much knowledge as possible to develop the best solution | –1.7 | 2.2 |

| My primary focus is to include organized actors of civil society | –1.0 | 2.0 |

| My primary focus is to included experts | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| –0.4 | ||

| Deliberative | ||

| I organize public participation processes to ensure that decisions are made against the backdrop of a rational, fair, transparent process | 3.0 | 1,7 |

| My goal is that at the end of a participatory process consensus and mutual understanding emerge | 1.5 | 2.1 |

| For me, a success is given when people have changed their minds or at least learn about other positions throughout the process | 1.0 | 2.5 |

| 1.8 | ||

| Emancipatory | ||

| I organize public participation processes to give marginalized groups a voice in decision making processes. | 0.3 | 2.0 |

| For me, a successful process is achieved when traditional power structures have been recognized and cracked | –1.6 | 1.6 |

| My long-term goal is to raise citizens’ political competences – particularly for individuals who are frequently overlooked by politics | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| 0.2 | ||

| Agonistic | ||

| I organize public participation processes in order to make conflictual positions salient | 0.9 | 2.0 |

| I think emotions and passions are central elements of public participation processes | 1.5 | 2.1 |

| It is my job to reveal conflict and dissent | 1.3 | 2.2 |

| 1.2 | ||

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for the fruitful and thoughtful suggestions. We also want to thank the editor, Nicole Curato, for her kind and constructive support throughout the publication process.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

1 Barnes, M., Newman, J., & Sullivan, H. (2007). Power, Participation and Political Renewal: Case Studies in Public Participation. The Policy Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.46692/9781847422293

2 Bherer, L., & Breux, S. (2012). The Diversity of Participatory Tools: Complementing or Competing with one Another? Canadian Journal of Political Science, 45(2), 379–403. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423912000376

3 Bherer, L., Gauthier, M., & Simard, L. (2017a). The Public Participation Professional: An Invisible but Pivotal Actor in Participatory Processes. In L. Bherer, M. Gauthier & L. Simard (Eds.), The Professionalization of Public Participation (pp. 1–14). Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781315637983-1

4 Bherer, L., Gauthier, M., & Simard, L. (2017b). Who’s the Client? The Sponsor, Citizens or the Participatory Process? Tensions in the Quebec (Canada) Public Participation Field. In L. Bherer, M. Gauthier & L. Simard (Eds.), The Professionalization of Public Participation (pp. 87–114). Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781315637983-5

5 Blumler, J. G., & Coleman, S. (2001). Realizing Democracy Online. A Civic Common in Cyberspace. IPPR.

6 Brown, S. R. (1993). A Primer on Q Methodology. Operant Subjectivity, 16(3/4), 91–138.

7 Chilvers, J. (2008). Deliberating Competence: Theoretical and Practitioner Perspectives on Effective Participatory Appraisal Practice. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 33(3), 421–451. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/01622439073075941

8 Chilvers, J. (2017). Expertise, Professionalization and Reflexivity in Mediating Public Participation. In L. Bherer, M. Gauthier, & L. Simard (Eds.), The Professionalization of Public Participation (pp. 115–138). Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781315637983-6

9 Chilvers, J. (2007). Environmental Risk, Uncertainty, and Participation: Mapping an Emergent Epistemic Community. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 40(12), 2990–3008. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1068/a39279

10 Christensen, H. E., & Grant, B. (2020). Outsourcing local democracy? Evidence for and implications of the commercialisation of community engagement in Australian local government, Australian Journal of Political Science, 55(1), 20–37. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2019.1689921

11 Cooper, E., & Smith, G. (2012). Organizing Deliberation: The Perspectives of Professional Participation Practitioners in Britain and Germany. Journal of Public Deliberation, 8(1), 1–41. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.125

12 Elstub, S., & Escobar, O. (2019). The Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance, Edward Elgar. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4337/9781786433862

13 Escobar, O. (2017). Making it official: Participation professionals and the challenge of institutionalizing deliberative democracy. In L. Bherer, L., Gauthier, M. & Simard, L. (Eds.) The Professionalization of Public Participation, Routledge.

14 Fung, A. (2003). Survey Article: Recipes for Public Spheres: Eight Institutional Design Choices and their Consequences. Journal of Political Philosophy, 11(3), 338–367. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9760.00181

15 Habermas, J. (1996). Between Facts and Norms. Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. MIT Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/1564.001.0001

16 Hendriks, C. M., & Carson, L. (2008). Can the Market Help the Forum? Negotiating the Commercialization of Deliberative Democracy. Policy Sciences, 41(4), 293–313. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-008-9069-8

17 Holtmann, C. (2019). Die privatisierte Demokratie. Das Progressive Zentrum.

18 Klages, H., & Vetter, A. (2013). Bürgerbeteiligung auf kommunaler Ebene. Perspektiven für eine systematische und verstetigte Gestaltung. Edition Sigma. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5771/9783845269849

19 Landwehr, C. (2014). Facilitating Deliberation: The Role of Impartial Intermediaries in Deliberative Mini-Publics. In K. Grönlund, A. Bächtiger & M. Setälä, (Eds.), Deliberative Mini-Publics. Involving Citizens in the Democratic Process (pp. 77–92). ECPR Press.

20 Lee, C. W. (2014). Walking the Talk: The Performance of Authenticity in Public Engagement Work, The Sociological Quarterly, 55(3), 493–513. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/tsq.12066

21 Lee, C. W. (2015). Do-It-Yourself Democracy: The Rise of the Public Engagement Industry. Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199987269.001.0001

22 Lewanski, R., & Ravazzi, S. (2017). Innovating Public Participation. In L. Bherer, M. Gauthier & L. Simard (Eds.), The Professionalization of Public Participation (pp. 17–39). Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781315637983-2

23 Linton, R. (1936). The Study of Man. Appleton-Century.

24 Lutfallah, S., & Buchanan, L. (2019). Quantifying Subjective Data Using Online Q-Methodology Software. The Mental Lexicon, 14(3), 415–423. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/ml.20002.lut

25 Maier, F. (2021). Citizenship from Below: Exploring Subjective Perspectives on German Citizenship. Political Research Exchange, 3(1), 1–23. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/2474736X.2021.1934048

26 Mansbridge, J., Hartz-Karp, J., Amengual, M., & Gastil, J. (2006). Norms of Deliberation: An Inductive Study. Journal of Public Deliberation, 2(1), 1–49. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2012.689735

27 Mill, J. S. (1971). Betrachtungen über die repräsentative Demokratie,. Schöningh.

28 Moore, A. (2012). Following from the Front: Theorizing Deliberative Facilitation. Critical Policy Studies, 6(2), 146–162. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2012.689735

29 Mutz, D. (2008). Is deliberative democracy a falsifiable theory? Annual Review Political Science, 11(1), 521–538. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.081306.070308

30 Newton, K. (2012). Curing the Democratic Malaise with Democratic Innovations. In. B. Geissel & K. Newton (Eds.), Evaluating Democratic Innovations. Curing the Democratic Malaise? (pp. 3–20). Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9780203155196

31 Parsons, T. (1952). The Social System. Tavistock.

32 Renn, O. (2008). Risk governance. Coping with uncertainty in a complex world. Earthscan.

33 Rottinghaus, B., Gerl, K., & Steinbach, M. (2020). DIID-Monitor Online-Participation 2.0. DIID-Précis. Retrieved from https://diid.hhu.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/DIID-Precis_Rottinghaus_et_al_2020-11.pdf

34 Ryfe, D. M. (2002). The Practice of Deliberative Democracy: A Study of 16 Deliberative Organizations. Political Communication, 19(3), 359–377. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/01957470290055547

35 Schöttle, S., Steinbach, M., Wilker, N., & Witt, T. (2016). DIID-Monitor Online-Partizipation Online-Partizipation in den Kommunen von NRW. DIID-Précis. Retrieved from: https://diid.hhu.de/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/DIID-Precis_Monitor-Online-Partizipation-2.pdf

36 Stephen, T. D. (1985). Q-Methodology in Communication Science: An Introduction. Communication Quarterly, 33(3), 193–208. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/01463378509369598

37 Stephenson, W. (1953). The Study of Behavior: Q-Technique and Its Methodology. University of Chicago Press.

38 Warren, M. E. (2009). Governance-Driven Democratization. Critical Policy Studies, 3(1), 3–13. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/19460170903158040

39 Watts, S., & Stenner, P. (2005). Doing Q Methodology: Theory, Method and Interpretation. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2(1), 67–91. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1191/1478088705qp022oa