1. Introduction

It is widely acknowledged among practitioners that facilitation matters in deliberative mini-publics, (see IAP2 2006; White et al. 2022) yet the differences between approaches to facilitation and their implications to the quality of deliberation have received relatively little attention among scholars of deliberative democracy (Escobar 2019; Moore 2012). We address this gap in the literature by examining how various approaches to facilitation lead to the realization of particular deliberative goals.

Our premise in this article is that the goals of deliberative mini-publics vary (see Steel et al. 2020). These goals include reaching mutual understanding, consensus or social cohesion, identifying problems or diversity in perspectives, or generating collective solutions to shared problems, to name a few (Curato et al. 2021; Fung 2003, 2007; Ryan and Smith 2014). We expect that different approaches to facilitation have various strengths and weaknesses, and what matters is identifying which approach to facilitation is best suited to realize a deliberative mini-public’s goal. How can we determine which approach to facilitation is suitable for particular goals?

To answer these questions, scholars of deliberative democracy must begin to systematically compare approaches to facilitation. We argue that not all approaches serve to achieve the same ends. Rather, there are different approaches to facilitation that can advance different deliberative goals. To test this assumption, we set up an exploratory study of three deliberative mini-publics on urban transformations in the German city of Magdeburg. Our main finding is that differences in facilitation approaches influence the process of deliberation in numerous ways, and that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to facilitating deliberative mini-publics. We see that deliberation can happen without a facilitator, but that facilitation can provide certain benefits. More stringent or involved facilitation, however, may not serve every purpose equally. There are trade-offs to be considered when designing, facilitating, or convening processes of citizen deliberation.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The importance of facilitation for deliberative mini-publics

The assumption that facilitation is necessary to ensure to the quality of deliberation in a mini-public is widespread (Beauvais and Baechtiger 2016; Curato et al. 2019; Elstub and Escobar 2019; Fung 2007). However, scholarly work on the internal workings of deliberative processes regarding especially the role of process design and facilitation remains rather limited. While practitioners of facilitation regularly consider which approaches to facilitation might best help achieve particular goals (Büro für Zukunftsfragen 2018; IAP2 2006; White et al. 2022), the scholarly literature does not yet provide a clear consensus on what the expectations on facilitation are, and how these are to be achieved (Escobar 2019).

There are, however, a few notable exceptions. Mansbridge et al. (2006) find that facilitators consider group atmosphere and progress toward the goal of deliberation as indicators of successful facilitation. Moore (2012) points out the need for a critical reflection on facilitation practices because they inevitably exist in a unique tension between ensuring and dominating deliberation. Dillard (2013) supports this, positing that facilitation methods vary along a scale of passive to involved, and that the role of the facilitator should not be seen as neutral because they help determine where deliberations go.

Asenbaum (2016) examines the characteristics of one particular facilitation method, dynamic facilitation, documenting how these facilitators address exclusionary tendencies and enable diversity while steering toward consensus. Molinengo and Stasiak (2020) argue that for facilitation, the planned interaction modes and material ‘artefacts’ used by facilitators can play a significant role in achieving (or impairing) collaborative advantage. As regards online deliberation, Trénel (2009) found that higher quality facilitation could minimize the effects of internal exclusion. Meanwhile, Wyss and Beste (2017) found that online forums using artificial intelligence-based facilitation can realize benefits in deliberative goals, improving deliberative interaction in numerous respects, other goals such as improvements in learning throughout the process were reached only for certain types of participants, with others experiencing undesirable effects.

2.2. Comparative studies on facilitations

Citing Dryzek (2000), Moore points out a set of expectations for facilitation: to make deliberative mini-publics ‘more inclusive, more comprehensive, more careful to avoid deception, suppression and coercion’ (Moore 2012: 148). The task of facilitation becomes yet more complex when these expectations are paired with different deliberative goals. The literature provides some insight as to facilitation applied in various cases, but the work of comparing facilitation methods systematically has only just begun.

Strandberg et al. (2019) compared facilitated and non-facilitated discussion among like-minded individuals, finding that facilitation—described as interaction rules upheld by a trained facilitator—reduces polarization in discussions among like-minded individuals. While Setälä et al. (2010) do not explicitly refer to facilitation, they compare two process designs in which facilitators led groups in different methods of decision-making. This is relevant here because process design reflects the particular goal that facilitators aim to achieve. The researchers find that while the different deliberative formats did not systematically impact the development of participant opinions, participants’ knowledge-increase as well as their consideration of the facts was higher with the consensus-oriented decision-making facilitation than with the format that decided via secret ballot voting.

2.3. The roles and goals of facilitation in deliberation

The literature shows various expectations from facilitation, but for the purposes of this article, we follow Escobar (2019), who identified inclusion, interaction, and impact as three expectations from facilitation (Escobar 2019: 183).

Inclusion refers to participation in deliberation and can be separated into two parts: internal and external inclusion. External inclusion is about who is invited or allowed to take part in a deliberation. There is significant attention to this in the literature, especially regarding representation and recruitment (Curato et al. 2021; Devillers et al. 2021; Dryzek and Niemeyer 2008; Elstub and Escobar 2019; Harris 2019).

Internal inclusion refers to the participation of all participants within a deliberation. When certain participants are overly dominant, the literature speaks of internal exclusion (Young 2002). Seen this way, the expectation is that ‘facilitation not only ensures that all participants have an equal chance to speak (achieving a more concrete equality of opportunity for participation), it also ensures that different sides of the debate are heard’ (Beauvais and Baechtiger 2016: 6).

Scholars expect facilitation to minimize internal exclusion by ensuring that all participants take part in deliberation (Dillard 2013; Escobar 2019; Moore 2012). One example of structural internal exclusion recognized by scholars that impacts internal inclusion is the gender divide (Einstein et al. 2019; Landwehr 2014; Young 2002). Scholars have documented ways that this form of exclusion manifests itself, for example that males speak longer and interrupt more often (Karpowitz and Mendelberg 2014; Mendelberg et al. 2014). Facilitation is expected to address this and other types of internal exclusion by designing and moderating interaction.

Interaction refers to the inter-group dynamics during the deliberation. Facilitators can affect this by establishing an interactive order through communicating rules, roles, or other norms and expectations. In order to better include all relevant arguments in a deliberation, facilitation in deliberative mini-publics can serve to counteract the [structural] power inequalities that otherwise threaten to be reproduced within the deliberative forum, for example by ‘encouraging and protecting’ participants (Landwehr 2014: 81). For example, a facilitator suggests an interactive order in which all participants are heard once before any are heard twice, or prompting quiet participants to contribute, protecting their contributions by physically positioning themselves between participants or ‘holding the space’ by prompting, focusing on, turning toward, looking at, and/or gesturing for a participant to speak while maintaining silence.

A facilitator might carry out none, some, or all of these interventions, and to varying degrees, depending on the goal and the approach. Dillard (2013) proposes a continuum of facilitations, from passive to moderate to involved. Landwehr (2014) also suggests a continuum of facilitation roles (or as she calls them: intermediary roles), suggesting various degrees of intensity in the tasks and roles. These range from organizing deliberation to enforcing interactive rules to interpreting and aggregating, resulting in different interactive orders.

Impact refers to what facilitation is able to achieve. Mansbridge et al. (2006) suggest that facilitation can impact upon group atmosphere, consistent progress toward the goal, and also increase participant satisfaction. Participant satisfaction is relevant, as some have argued that positive experiences deliberating effect factors important to acceptance and readiness to partake in deliberative democratic processes (Dienel 2002a; Landemore 2020). Boulianne et al. (2020) suggest that facilitated deliberation leading to the perception of a higher quality deliberation can increase civic and political engagement more than when deliberative standards are lower.

There is relative consensus in the literature that facilitation should be impartial, regardless of whether it is more passive or involved in enforcing interactive orders (Dillard 2013; Escobar 2019; Landwehr 2014). However, impartiality can conflict with expectations of inclusion, interaction, and impact, if facilitators use their position as an impartial party to promote more inclusive processes. Doerr (2018) describes how the position as a ‘disruptive third’ has been used on behalf of facilitators committed to the goal of inclusion and how this unique position can be effective in better achieving this goal.

2.4. Practice-oriented literature on facilitation

There are numerous guidelines, toolkits, outlined approaches, and processes available to facilitators. These range from foundational underpinnings based on theory and experience and elaborated with examples (for example Kahane 2021; Scharmer 2009) to dedicated works offering detailed practical and methodological orientation. Amongst the latter are guidelines for specific facilitation methods; for example, Dienel (2002b) on the planning cell, Zubizarreta (2014) on dynamic facilitation, or White et al. (2022) on variations of mini-publics. There are also toolkits and guidelines that include various facilitation methods according to the context and goal of the deliberation (Büro für Zukunftsfragen 2014; IAP2 2006). The IAP2’s Public Participation Toolbox clusters its tools in different categories, suggesting different goals. Listed are techniques to: share information, compile and provide feedback, and bring people together (IAP2 2006).

Practice-oriented materials can be found that cover the range in the spectrums of facilitation roles (Dillard 2013; Landwehr 2014), some methods and approaches demanding more resources than others. These resources can include time (the duration of the process and preparation and postprocessing), training of the facilitators, and material requirements. Facilitation methods also vary in terms of goals and expected outcomes. The practice-oriented literature clearly seeks to match facilitation approaches with goals of (mini-public) deliberation, while scholarly literature has yet to systematically address this relationship. This points to the gap in scholarly literature that needs to be addressed and to which we aim to contribute to with this article.

2.5. The limits of facilitation

The expectations projected upon facilitation are many, and they have been more thoroughly documented than the extent to which facilitation can meet them. The practice-oriented approaches, methods, and materials set different emphases. The question is: can facilitation achieve all the deliberative goals at once? Encouraged by the practice experience and practice-oriented literature, we argue that this is not the case.

‘Clearly, the role and tasks of the intermediary will differ depending on the precise set-up of the deliberative forum’ (Landwehr 2014: 89). Following Landwehr (2014) and other colleagues who have acknowledged the variance between facilitations, we expect that to achieve specific facilitation goals, the purpose of a mini-public’s format must be appropriately matched with a facilitation design. As illustrated above, comparative work on facilitation remains scarce. Although interest in comparative facilitation work is growing (Escobar 2019), obstacles for scholars pursuing this work also remain significant (Landwehr 2014).

3. Comparing facilitations: three deliberative designs

To add to the insights on comparing facilitations, we developed three facilitation designs for three mini-publics that we co-designed with the city administration of Magdeburg, Germany. We chose facilitation approaches that varied substantially, but the task given to each mini-public stayed the same. Table 1 shows the tasks of facilitation from Landwehr (2014) that were fulfilled by the respective facilitation format, and Box 1 describes the facilitations.

Landwehr’s (2014) facilitation tasks, whether present in each facilitation format. (SO = Self-Organized; MM = Multi-Method; DF = Dynamic Facilitation.)

| SO | MM | DF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutionalizing deliberation | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Enforcing procedural rules | No | Yes | Yes |

| Rationalizing communication and keeping emotions at bay | No | Yes | Yes |

| Ensuring internal inclusion and pluralistic argumentation | No | Yes | Yes |

| Summarizing, aggregating, and decision-making | No | Yes | No |

Box 1:

Self-Organized: SO deliberation is a minimally-facilitated approach. The participants received the uniform briefing, which outlined the task and introduced them to the available materials (map, markers, and idea templates), and the three hour timeframe. The tables were placed in the middle of the room and the materials put on the tables. There was no facilitator.

Multi-Method: The MM deliberation was facilitated by a professional facilitator according to the process designed by the authors in cooperation with the facilitator considering the group’s task. Process design elements were introduced to help participants feel comfortable in the setting and with one another, and to encourage understanding of the purpose of the process, the task, and its relevance. Tables, chairs, and flip-charts were positioned differently throughout the deliberation according to the needs of the techniques. Techniques such as telephoning acquaintances who might have different ideas than oneself, and previously researched citizen profiles used to introduce perspectives not represented within the group. Participants were at certain intervals asked to work individually, in pairs, in smaller groups, and as a whole group. These elements were included in an overarching process design, which aimed first to widen the potential and possibilities for creative idea development, and then to narrow discussion to make precise recommendations.

Dynamic Facilitation: The DF deliberation was facilitated by a professional facilitator trained in the method. Tables were pushed to the side, chairs were in a row facing 4 flip charts. The facilitator was instructed to apply DF in its textbook form, sticking as close as possible to a pure form of the method. It should be noted that DF would often require somewhat more time than was available in this case.

3.1. The context of deliberation in all three designs

Seventeen citizens took part in the deliberative mini-publics. They were recruited through invitations sent to a random sample of 702 citizens from the official city registry distributed equally according to age and gender, of which 13 participated in the deliberation. A further four participants were recruited using an intercept method, approaching citizens at random along a pre-defined path in Magdeburg’s city center. (For a more detailed description of the recruitment, see Molinengo and Stasiak 2020: 6.) The mini-publics were carried out in in Magdeburg’s city hall in June of 2019 in accordance with German data protection and privacy regulations. All participants consented to the mini-publics being recorded and analyzed by the researchers.

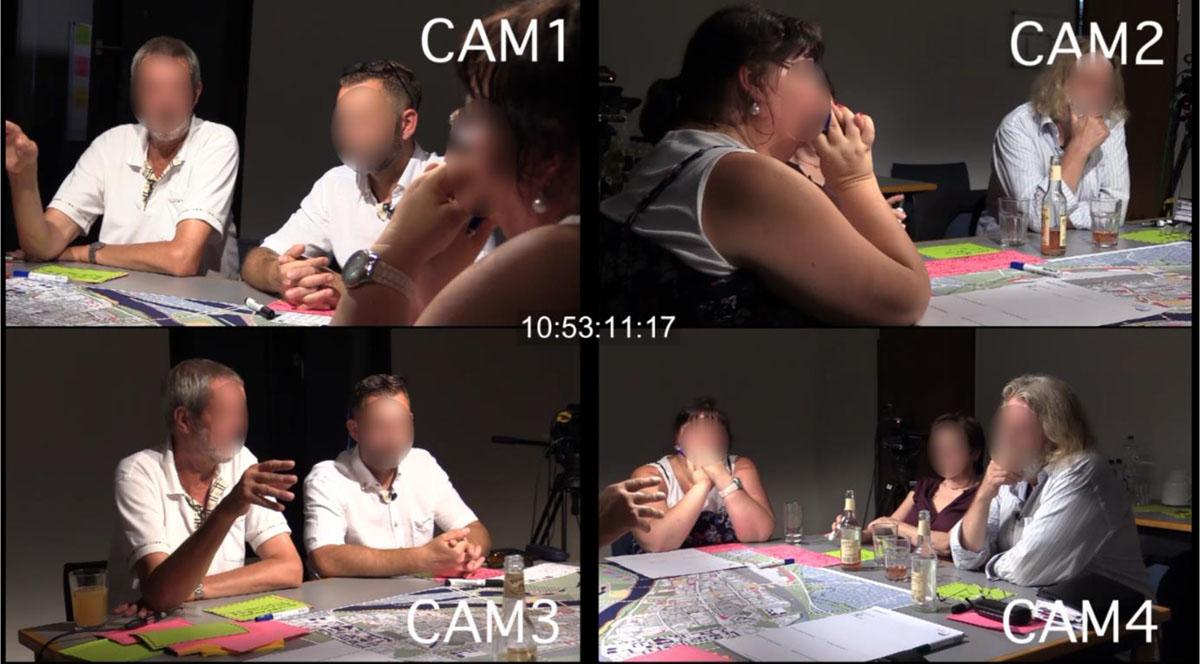

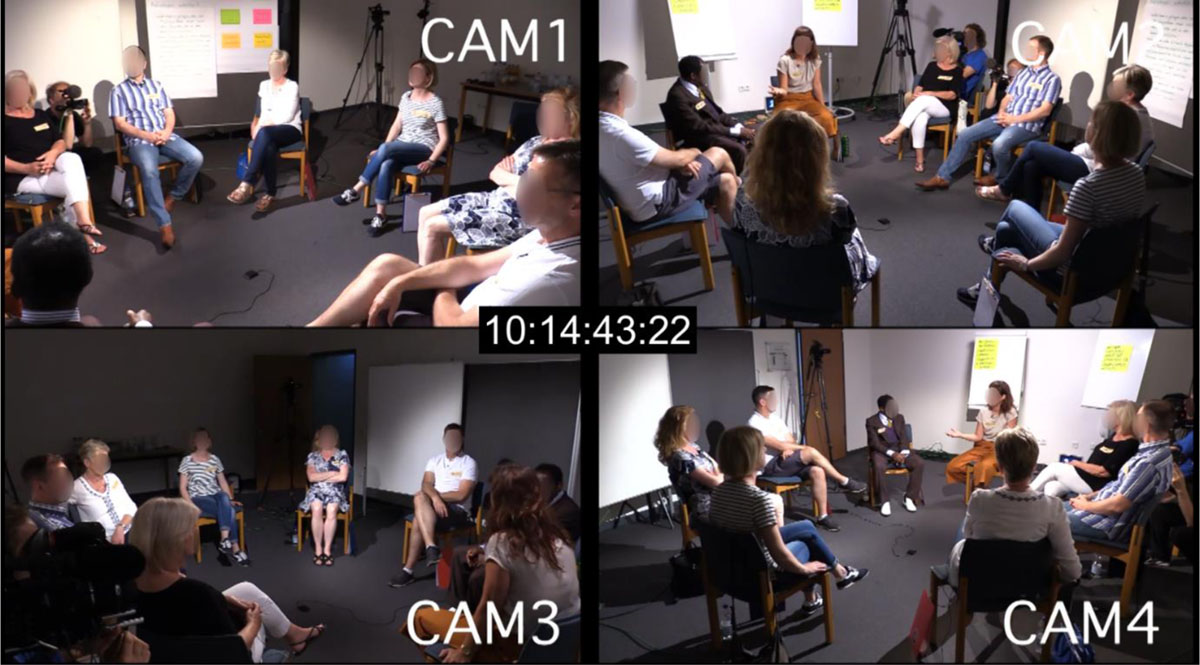

We worked with a media team from the regional state television station MDR to make video recordings of the deliberations. We analyzed the recordings to determine the speech time of each participant, and to identify the individual speech acts, qualifying whether the speech act was an interruption and whether the speech act took place in the plenary or in smaller groups. To supplement the video analysis, we collected data from the participants using post-deliberation surveys. Thus, we aim to generate preliminary insight regarding the different functions of deliberative processes as regards differences in facilitation.

Due to the real-world nature of the mini-publics, constraints regarding participants, facilitation design, and the limited time-frame of three hours for each process, the generalizability of the insights is limited. Our exploratory approach instead provides initial insight and a point of departure for more systematic comparison of facilitation approaches.

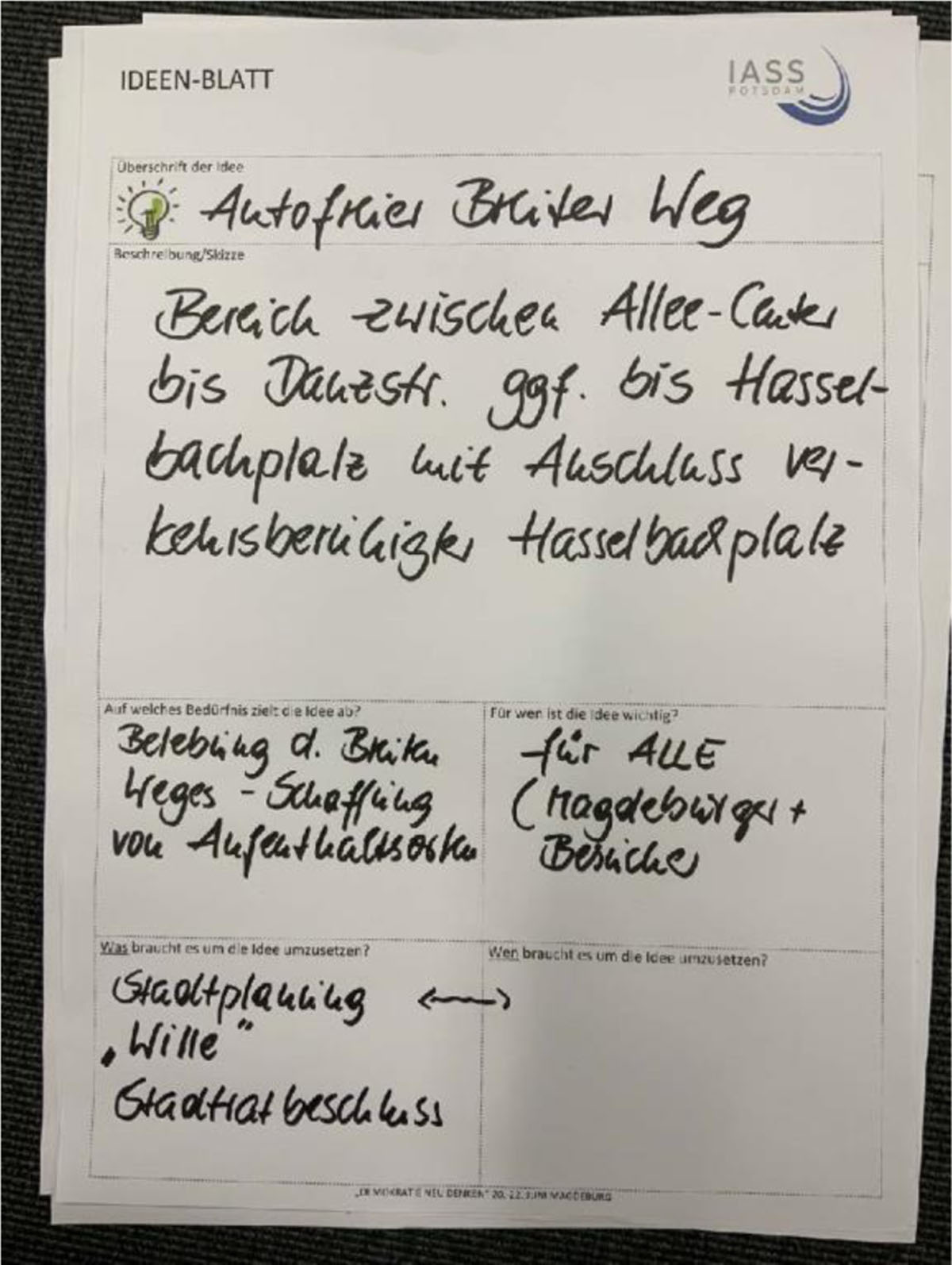

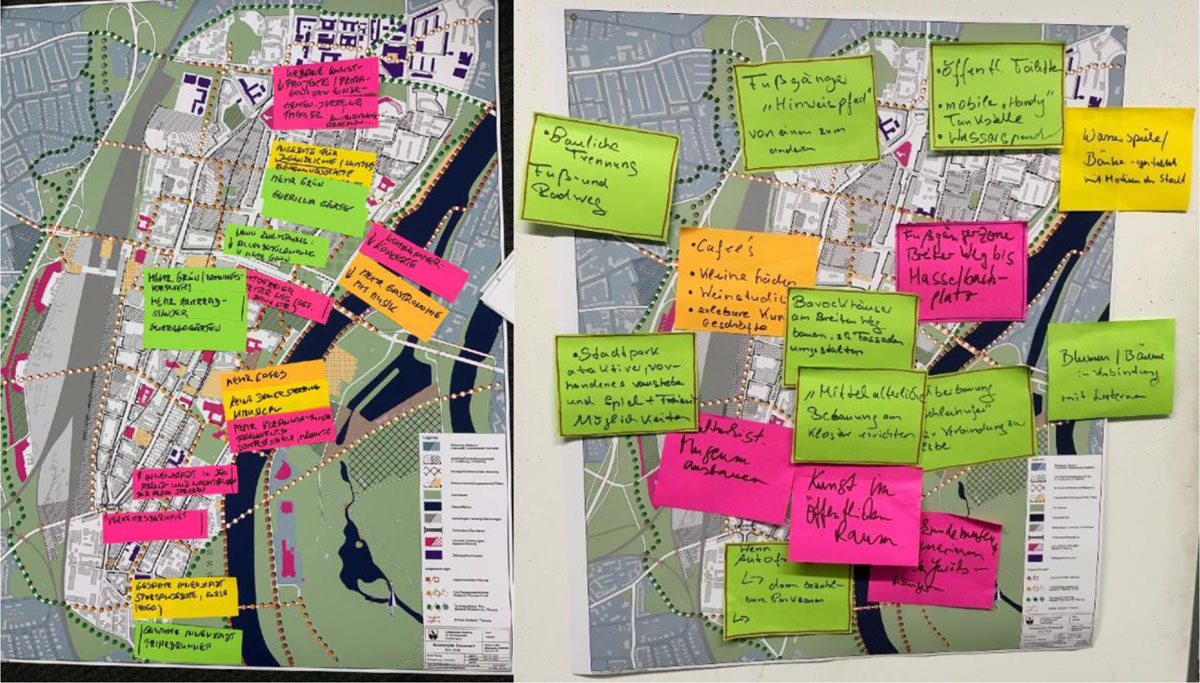

The participants were divided into three groups: the self-organized (SO) group with five participants, the multi-method (MM) group with seven participants, and the dynamic facilitation (DF) group with five participants. The uneven distribution of participants between the groups was due to last-minute cancellations. The task of each group was to generate recommendations in response to the question: ‘How can the city center of Magdeburg be made more pedestrian friendly?’ (Wie kann Magdeburgs Innenstadt für Fußgänger attraktiver werden?) All mini-publics were asked the same question. They also received the same briefing at the beginning, outlining their task and the resources available to them. All were instructed that they had three hours to come up with and document their recommendations. They were also given the same working material, including templates for collecting and documenting their recommendations. All groups were told that their recommendations would be received and reviewed by the City of Magdeburg and would serve to inform the city development strategy. We designed the templates following consultation with city officials so that they could be easily understood by the city administration.

There were two different types of response-templates (see Figures 1 and 2). Each group was also provided with markers and a large map of the city center of Magdeburg (seen in Figure 2). Although each group received the same introduction and materials, how and when these were applied depended on the process. For a more detailed examination of how the materials were used in the different groups, see Molinengo and Stasiak (2020). The following sections examine the three different facilitation designs.

sticky-notes as response templates were color-coded to correspond to five categories, plus a wild-card color to allow for responses not foreseen in our categories. The categories were: Repurposing Street-Space, Art and Culture, Nature, Stores and Commerce, Places (to be), and Other.

3.2. The self-organized approach

The process design of the self-organized (SO) mini-public (see Figure 3) was limited to the introductory briefing, which identified the task and introduced the response-templates. Participants themselves established various roles within the mini-public. Participants assumed or tried to pass on roles, but these roles were often not firmly established and maintained. It was never explicitly established when either a topic or the overarching task was fulfilled. This, coupled with a lack of maintained focus on topics for longer periods, suggests that the SO process was characterized by a lack of orientation. There was also no systematic attempt to ensure internal inclusion. Nonetheless, there was a certain deliberative quality to be observed. The participants supplied reasons for their suggestions and engaged with the contributions of others and filled out the response templates.

Lacking a facilitator, the interaction mode was left open. At the beginning, a male participant established himself in a moderating role by suggesting an approach to gathering and sharing ideas:

So I suggest, we take one point at a time, everybody takes for the point a colored note, shares their ideas like what one comes up with, and then we could maybe combine and summarize for that point. Yeah? (Participant 1M1, 20.06.2019)

We noted that the body-language of other participants suggested that not all participants seemed to equally support this suggestion. We observed a frown, raised eyebrows, and leaning away from the participant. Nonetheless, this decision was not contested. This suggestion was upheld for the remainder of the process, although the participant who suggested it filled the role with less clarity and energy as time went on. This participant had the highest speech time (31.4%) of the participants in the group.

One participant assumed the role of timekeeper, who reminded the group of how much time was left. Another participant left before the group was finished (after 1 hour 30 minutes), which seemed to cue to the rest of the group that the process was nearing the end. The SO group ended the process after 1 hour 45 minutes, with a bit of uncertainty. One participant asked the others ‘Do we have to sit out the time?’ (1F4)

The participants discussed without explicitly allocating speaking turns. The categories of the response templates were intermittently referred to and served as a minimal structure for organizing the content of the discussion. While this structure was mostly in the background, it helped organize the discussion. One female participant had been designated by others as the scribe, supported by comments like ‘Women mostly have better handwriting’ (1M1), ‘That’s true’ (1M5). The scribe used the template to maintain focus on a topic. When the participant who had taken on a moderating role said, ‘Should we…em, next topic?’ (1M1), the scribe pointed with her pen to the headings on the template and said ‘well, we have to still…’ (1F3) and then read aloud the template prompt. She used the template to maintain focus on the topic until the question was answered, sometimes adding instructions so the group would provide the kind of response she felt was appropriate to write in ‘They want a bit more detail, like street names’ (1F3). While this was successful at getting participants to interact by supporting, opposing, or qualifying others’ ideas, the topic of discussion often jumped from topic to topic. This led to many topics being left open or unfinished, without an explicit indication whether this was the will of the group or happenstance.

3.3. The multi-method approach

The multi-method (MM) (see Figure 4) mini-public showed the highest participant satisfaction and the greatest readiness to engage in city development. Through meticulously planning the mini-public, the facilitator sought to create a constructive environment and constantly keep the process moving forward by including various interactive moments, safeguarding reflection time, and by using first names, establishing goals and sub-goals, giving the participants ownership of the process by having them reiterate the task with their own emphasis. The participants came up with ideas, reflected on them, shared them, and developed further ideas together. The facilitator established and maintained an orientation (‘Is it clear what we’re doing?’) and bundled smaller tasks that built upon each other to achieve the main task but helped make clear the orientation of what the participants were doing at any given time.

The mini-public began with a plenary session. The facilitator (with whom we designed the MM process) received the participants in a circle of chairs. She told participants what to expect from the mini-public. She also organized an activity to let participants get acquainted with one another. The facilitator led the participants through the process design, which oscillated between interaction in the plenary, in smaller groups, and individual tasks. This encouraged repeated moments of reflection—for participants to become consciously aware of their own positions and ideas—followed by moments of sharing and reaction. And there were phases where participants spoke on the telephone with people outside of the group or were given fictional profiles based on real individuals observed and spoken to in the Magdeburg city center to study and consider. The goal of these phases was to encourage participants to think in a way that considered the needs and perspectives of others in relation to their own. The interaction mode was thus lively but at the same time often agreeable and organized. The facilitator encouraged participants to speak with and listen to one another. All participants engaged in the process until the facilitator declared the end, after 2 hours 30 minutes.

Different from the other processes, at the beginning the facilitator asked if it would be acceptable to address one another on a first name basis, which the group agreed to and did. The facilitator had participants share their own experiences in groupwork to emphasize the importance of listening. She also gave advice on how to listen and contribute constructively, for example saying:

A generative listening, or a creative listening. It’s, well, you know, maybe like when you’re sitting with friends or with your family, and then someone says something, and someone shares an idea, then someone else shares an idea, then a third person shares an idea, and suddenly, there’s an idea there that wasn’t there before. And you can’t exactly say ‘that’s what you said.’ But somehow it’s emerged. […] Have any of you experienced this kind of listening? Yeah? Who’s got an example? (MM Facilitator, 22.06.2018)

Thus, the facilitator created a positive feeling in the group by emphasizing the benefits of working together. While the facilitator used prompts to bring people into the deliberation, they were often embedded in the overarching plan that had been established. Rather than a typical ‘calling on’ participants to continue, the facilitator prompted people to not just say something, but to contribute to the progress of the process. ‘Ralf and Adam, what else did you guys find out?’ Or, to encourage interaction with ideas: ‘So when you listened to that, the concepts, the ideas, where did your heart warm up?’

The facilitator emphasized certain norms of interaction, making the participants a part of their establishment for the group. At rare points, she also clearly re-established the rules of interaction. For example, while gesturing between two groups: ‘Ok, there’s the one rule though: you guys get to speak, and you guys get to listen’ (MM Facilitator).

3.4. The dynamic facilitation approach

In the dynamic facilitation (DF) mini-public, the process design determined the interaction mode: speech interaction was dialogue between the facilitator and a single participant at a time, with the facilitator asking prompting questions to elicit more elaboration on ideas from the participant while the other participants listened. Relative to the other two processes, participants spoke for fewer, but much longer turns, and watched as their ideas were written down and filled the room around them.

The facilitator of the DF process began with a round of introductions, with the participants sitting in a half-circle. After the introduction, the facilitator changed the setting (see Figure 5), asking the participants to move their chairs into a line all facing the facilitator and four flip-charts, saying ‘…so that you are all not like just now in a circle speaking with each other, but speaking with me.’ She explained the mode of interaction, the rules and what participants could expect. She said:

What might seem somewhat strange or even confusing, is that we will not work on this question—how can Magdeburg’s city center become more pedestrian friendly—we will not systematically work to answer this question, as in first point, second point, third point. Rather, it can really seem somewhat chaotic. That means we will be jumping, in the sense of that has to do with our four charts, each of which has a title (DF Facilitator, 21.06.2018).

She then read aloud the titles of the four charts (Solutions/Ideas, Concerns, Information/Perspectives, Questions/Challenges). The facilitator explained what she would do (‘I listen, and I write what I hear onto the paper’) and explained what she meant with the jumping: ‘You can imagine it as if you’re doing a puzzle together. One person is doing the sky, another person is looking for all the green pieces. And a third person tries to find out the corners. And to the extent that we over time are busying ourselves with all these pieces, the bigger picture emerges.’ (DF Facilitator)

The facilitator then announced she would now listen to each participant speak about their thoughts on the question at hand and did this one by one. Each participant spoke for as long as they wanted, their turns protected by the facilitator, who held the space by concentrating on current participant with eye-contact, focus, and hand gestures. The facilitator wrote many of their points on the four flipcharts, sometimes asking if the formulation was correct or if it was on the correct flipchart and hanging the poster-sized papers on an adjacent wall when full. Another round in the same format followed, with the facilitator emphasizing that participants should follow ideas that evoked emotions. The facilitator held the space for the participants to finish their thoughts, telling other participants that their turn would come if they began to speak out of turn. In this way, the facilitator allowed and encouraged participants to fully share, without pressure to quickly get to the point or finish. When participants voiced concerns or described problems, the facilitator would often respond with: ‘Ok. Do you have a solution or idea for that?’ and write down their responses.

Our observation of the participants’ body language suggested that it required energy to listen to the long speech contributions of the other participants. Participants who were not speaking shifted in their seats, cradled their heads in their hands, or twiddled their thumbs. The facilitator had prepared them for this: ‘That’s when your patience is needed.’ The participants in the DF process were engaged in the process the whole time, beginning and ending together, for 2 hours 45 minutes. During that time, they were together in the plenary, except for 20 minutes toward the end when they split up into 2 smaller groups as directed by the facilitator. During these 20 minutes, the participants filled out the response templates, considering what they had just heard and experienced.

4. Comparing Facilitations

All facilitation approaches enabled deliberation, but in different ways and had different strengths and weaknesses. Here, we map out the three facilitation processes qualities along Escobar’s (2019) facilitation ideals of inclusion, interaction, and impact.

As regards inclusion, we find processual elements in both the MM and DF mini-publics that ensured that all participants contributed to the outcome. But the DF approach did this more stringently. The DF facilitator guarded participants’ contributions from pressures from impatience of other participants, encouraging participants to fully share their thoughts with prompts while maintaining eye-contact: ‘is that all?’ or ‘anything else?’ This creates a positive potential to contribute, even if participants are hesitant or quiet. Thus, DF most strongly counteracted potentials for internal exclusion. The MM process ensured the potential for each participant to contribute in a less institutionalized way—relying heavily on the perception and skill of the facilitator. SO-type processes will be least effective in ensuring internal inclusion as there is low potential to counteract dominance or timidness of participants.

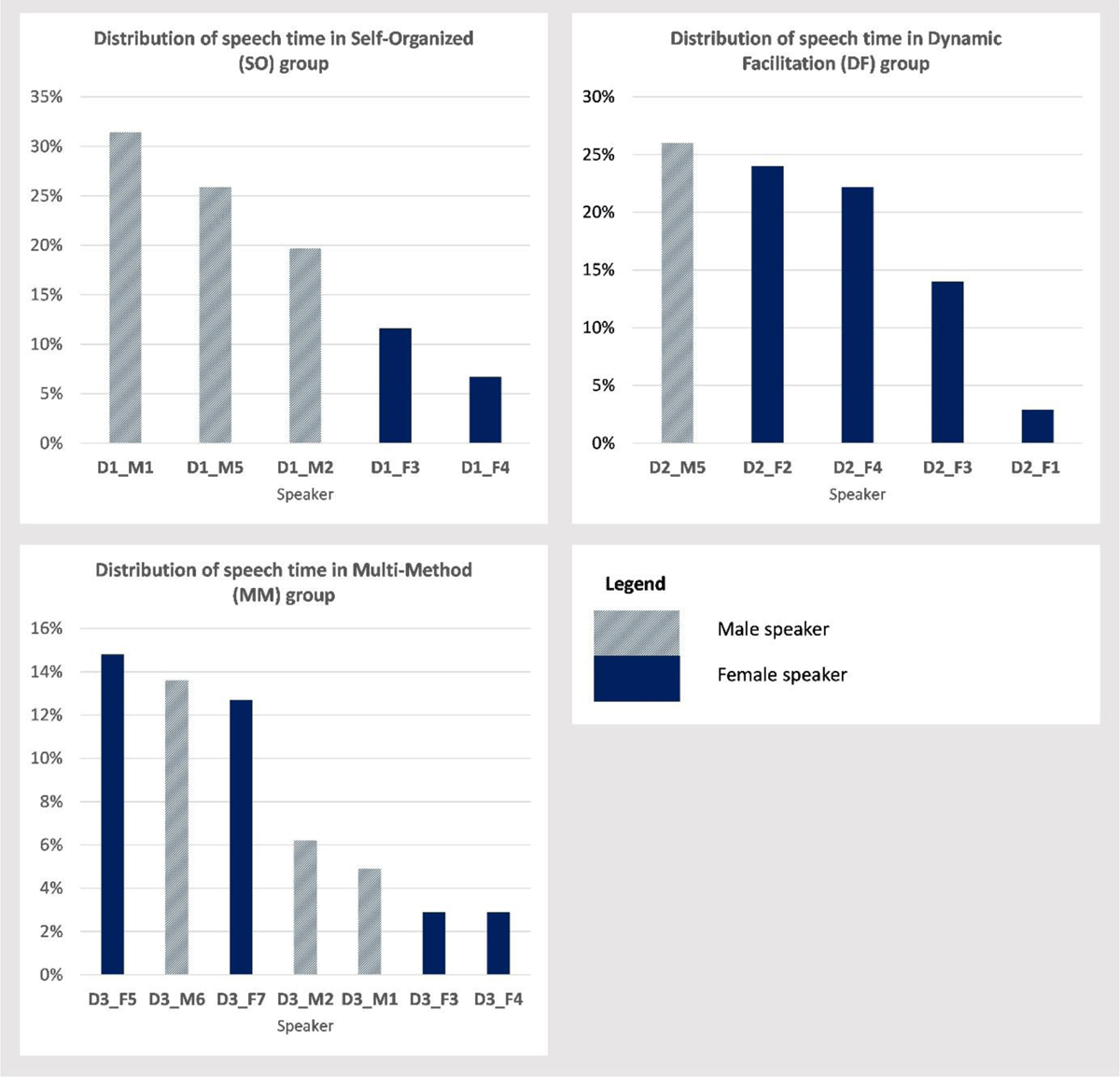

As a caveat, it was also reflected in the surveys that the participants in the DF process found it more difficult than participants in the other processes to bring their ideas into the process. Also, in each of the processes, some spoke less, others more. Our quantification of speech time for each participant showed that the distribution of speech time displayed similar patterns, regardless of facilitation (see Figure 6). We found this similarity surprising. Also, certain structural asymmetries mentioned in the literature were observable: in each of the three mini-publics, the two participants with the lowest speech time were females.

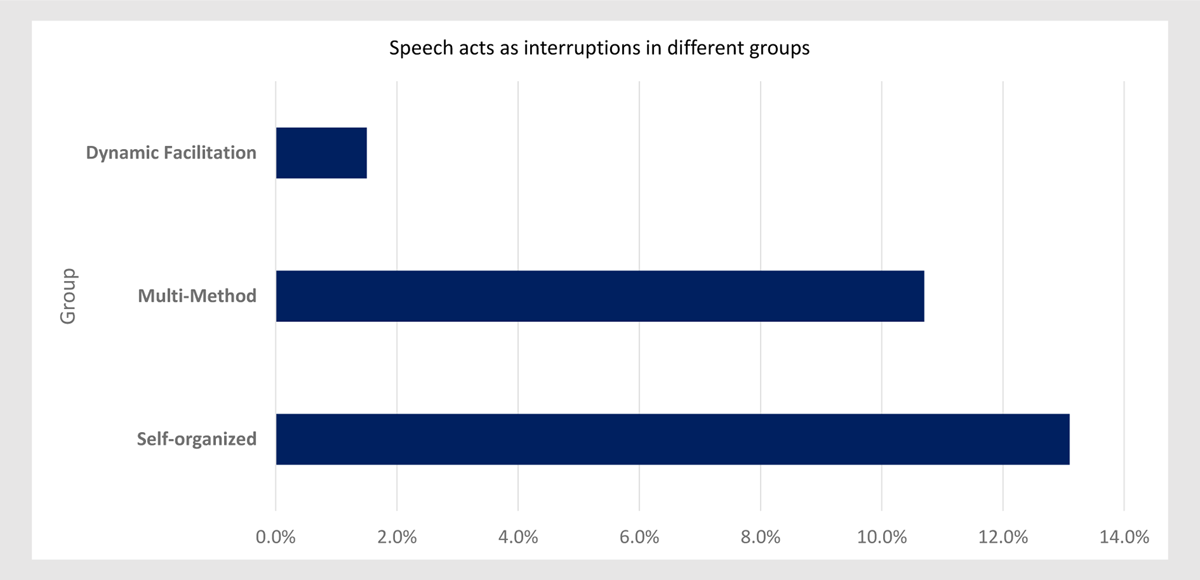

In terms of interaction, the rigid interactive order of DF contrasts with the lighter-hearted, more collective-oriented interactive mode of the MM process. The DF mini-public showed the longest contributions and fewest interruptions (see Figure 7). But contributing ideas in the DF process was perceived as the most challenging. Still, perception of the most widely differing perspectives was also reported from the DF participants. This may be an indication that DF is appropriate when participants have a higher interest in or commitment to the outcomes and are thus willing to undergo a more demanding interaction in a mini-public.

The indication is that DF foregrounds what Goodin (2000) refers to as the ‘internal-reflective’ aspects of deliberation, and while eliciting thoughts and emotions from deep within might not be easy, it could be that it is helpful. And if so, DF may be an apt method. The other side of this dichotomy are the ‘external-collective’ aspects of deliberation. These were emphasized more in the MM facilitation. In the MM process, we observed a much stronger orientation toward the maxim that ‘what deliberating groups should strive to achieve, then, is something close to friendship’ (Mendelberg et al. 2014: 35). Along with triggering creativity by encouraging reflectivity, the MM process was designed to promote a positive group atmosphere, which has been recognized as an important goal of many facilitators (Mansbridge et al. 2006). The participants in the MM process supported this notion by indicating a substantially higher readiness to become active with others to help shape their city than participants in the other two processes, which was lower in the SO and lowest in the DF mini-public (question 2 in Table 2).

Post-Survey Questions (SD = standard deviation).

| Post-Survey Question | SO Average (SD) | DF Average (SD) | MM Average (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | I will become active by myself to help shape the city. | 4.0 (0.89) | 3.6 (1.02) | 5.0 (0.00) |

| 2. | I will become active with others to help shape the city. | 4.0 (0.63) | 3.2 (0.75) | 4.9 (0.35) |

| 3. | I could imagine taking part in this type of process again. | 5.0 (0.00) | 5.0 (0.00) | 5.0 (0.00) |

| 4. | I am satisfied with the outcome of the event. | 3.8 (0.75) | 4.8 (0.43) | 4.9 (0.35) |

| 5. | I am satisfied with the procedure of the event. | 4.4 (0.80) | 4.6 (0.49) | 4.8 (0.37) |

| 6. | It was easy for me to bring my ideas into the process. | 4.6 (0.49) | 4.2 (0.75) | 4.4 (0.49) |

| 7. | I would never have come to the ideas developed in the event on my own. | 3.2 (1.17) | 2.6 (1.02) | 2.7 (0.94) |

| 8. | How different were the perspectives that were brought into the discussion? | 1.8 (0.98) | 4.2 (0.98) | 1.3 (0.70) |

| 9. | To what extent did you learn new things through participation in this event? | 3.0 (1.79) | 3.8 (0.98) | 3.6 (0.90) |

Varied readiness to further engage is a noteworthy result in terms of impact. Further, uninterrupted expression and listening have been said to contribute to the normative goals of deliberative processes by creating ‘possibilities for mutual learning and opinion change’ (Asenbaum 2016: 3). Participants in the DF process that showed the longest phases of uninterrupted expression indicated the greatest difference between the perspectives of the participants. And participants in the DF mini-public also reported higher learning, followed closely by the MM group with much lower reported learning in the SO group. This further supports the notion that the impact of different facilitations varies.

The SO group demonstrated that deliberation is possible also without a facilitator. The group members divided roles that were otherwise fulfilled by the facilitator in the other processes, such as process-designing, time-keeper, or scribe. These roles helped the group achieve their task, but they did not fill out the roles of facilitation tasks and functions as described by Landwehr (2014). It is important to note that the SO process was not completely free of facilitation. While no facilitator accompanied the deliberation, a minimal facilitative structure was given through the initial briefing, defining the task and introducing the response-templates, which participants were asked to use to organize their process.

5. Conclusion and future directions

Our exercise in mapping different facilitation designs and practices reinforces the notion that differences in facilitations influence the process of deliberation in numerous ways. We have provided an abridged comparison in Table 3. For instance, when internal inclusion or identifying the spectrum of perspectives is the priority, DF is likely most reliable. If increasing civic engagement or achieving cohesion are most desired, a process akin to the MM approach will serve better. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to facilitating deliberative mini-publics.

Comparison of selected aspects of the three facilitation formats.

| Self-Organized (SO) | Multi-Method (MM) | Dynamic Facilitation (DF) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impartial trained Facilitator | No | Yes | Yes |

| Materials unique to facilitation requirements | None | Various. (In our process: 2 Flip-Charts; papers with citizen profile-templates printed on them (e.g., a delivery driver; a young woman who uses a wheel chair, etc.); Sticky-note templates were cut into smaller sizes |

4 Flip-Charts |

| Main Group Format | Plenary | Varying: plenary, small groups, individual work all used | Plenary |

| Main interaction with | Other participants | Other participants | Facilitator |

| Room Set up | Tables and chairs in middle of room | Various, according to the needs of the current process step | Chairs in a row facing 4 flipcharts, Facilitator between participants and flipcharts |

| Described in literature | Planning Cell (Dienel 2002b); some Citizens’ juries (Crosby and Hottinger 2011) | (Büro für Zukunftsfragen 2014; Scharmer 2009) | (Zubizarreta 2014; Asenbaum 2016; Rough 2002) |

| Role-intensity of Facilitator (Dillard 2013) | Passive | Moderate | Involved |

| Strengths | Requires few resources | Tailored to the goals of process Potential for high internal inclusion |

Can facilitate common solutions to complex problems Acknowledges each participant’s perspective High internal inclusion |

| Weaknesses | Risk of internal exclusion, inconclusive deliberation, and/or lower participant satisfaction | Impossible to standardize, high level of training and wide competencies for facilitator required | Demanding process for participants with long moments of intense listening |

SO-type processes can work; this way, deliberation can occur with fewer resources, but it is vulnerable to domination and not particularly satisfying as regards output and, possibly, learning. By using artifacts like response templates or detailed instructions, some benefits of facilitation might be able to be realized without the presence of a facilitator (Molinengo and Stasiak 2020). Facilitation designs like the MM process can bring people together and motivate them; this can be helpful when working together is desirable. But the lack of standardization may incur higher costs, need better trained facilitators, and be difficult to predict, influence, or handle. Depending on the context, convenors may be dependent on individual facilitators’ skills and experiences. DF can serve well to identify the spectrum of perspectives or needs, promote mutual understanding, or help clarify problem definition. But it is demanding of participants, as it requires concentration while individual participants speak over a long time. Thus, we are led to suspect that that facilitations in practice may serve contrasting purposes analog to the contrasting expectations found in the literature.

Practically speaking, convenors and facilitators may be faced with choosing which normative expectations to prioritize. It is unlikely that one facilitation can adequately address all or even most of the manifold expectations projected upon deliberation. Clarity regarding the goals of the process design, and the ability to access and decide on accordingly selected methods and strategies available for practicing the interaction mode, is crucial for convenors and facilitators alike. To this end, convenors of deliberative processes need to be better equipped when selecting facilitations.

Where reaching consensus is the goal, it might seem as though—due to the harmonious atmosphere—it be best achieved with facilitation like the MM process. But it is likely more complex. Although the MM process created a positive and cooperative atmosphere, if the requirement is working or living with the consensus beyond the deliberation, convenors of deliberation might be well advised to consider investing in deliberation that reveals deeper-seated motivations. Identifying these early and searching for consensus in a situation with widely diverging positions can make a consensus more durable, even though this shifts more work toward the beginning of the process.

5.1. Further research

Further research comparing facilitations should aim to help convenors of deliberative formats better judge what facilitation designs will serve their needs and which facilitators are best equipped to carry out that facilitation. Convenors, especially when it comes to public sector convenors commissioning deliberation as a part of democratic processes, should be making informed decisions to make the facilitation fit the task of deliberation. Without identifying pluralities and differences within facilitation design and practice, and establishing standards or guidelines, this remains a challenge.

We need more research to establish categories and standards for facilitation, and to sharpen the indicators we will use to see whether facilitations are living up to their promise and potential. Work done on identifying categories and tasks of facilitation, and the roles of facilitators, is extremely valuable (Dillard 2013; Landwehr 2014; Mansbridge et al. 2006; Moore 2012), but researchers will need to get into more detail and importantly, connect their categories and standards closely to facilitation practices. To this end, close collaboration with the emerging communities of practice that are growing around certain facilitation methods such as dynamic facilitation or approaches such as the Art of Hosting can be useful.

To sharpen the indicators, for example, we will need to develop concepts beyond speech time to measure internal equality, as has already been suggested (Escobar 2019; Landwehr 2014). Indicators for good listening will also be helpful. The quality of listening may prove difficult to capture, but Scudder (2020b, 2020a) offers a fertile point of departure. Developing a nuanced understanding of different facilitations would be a valuable step to better enabling deliberation and its practical ability to further deliberative-democratic practices.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants in the mini-publics, the City of Magdeburg, the WTS MixedMedia Film Team, the Facilitators Karolina Iwa and Ellen Gürtler, and our colleagues Nicolina Kirby and Giulia Molinengo. We also express our gratitude to the two anonymous reviewers and the editors for their generous and helpful feedback.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

1 Asenbaum, H. (2016). Facilitating inclusion: Austrian wisdom councils as democratic innovation between consensus and diversity. Journal of Public Deliberation, 12(2), 11. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.259

2 Beauvais, E., & Baechtiger, A. (2016). Taking the goals of deliberation seriously: A differentiated view on equality and equity in deliberative designs and processes. Journal of Public Deliberation, 12(2), 2. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.254

3 Boulianne, S., Chen, K., & Kahane, D. (2020). Mobilizing mini-publics: The causal impact of deliberation on civic engagement using panel data. Politics, 40(4), 460–476. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0263395720902982

4 Büro für Zukunftsfragen. (2014). Bürgerräte in Vorarlberg: Eine Zwischenbilanz. Büro für Zukunftsfragen. https://www.kommunikation-vorarlberg.at/finder/1d234662-d1de-4095-9761-9828914b9466/8642e86bb41f33372e9ba08c98a24e92/zub-burgerrate-zwischenbericht.pdf

5 Büro für Zukunftsfragen. (2018). Handbuch für eine Kultur der Zusammenarbeit: “Art of Hosting and Harvesting” in der Praxis. Bregenz. Büro für Zukunftsfragen Vorarlberg.

6 Crosby, N., & Hottinger, J. C. (2011). The citizens jury process. In Council of State Government (Ed.), The Book of the States 2011 (pp. 321–325). Council of State Government.

7 Curato, N., Farrell, D. M., Geissel, B., Grönlund, K., Mockler, P., Pilet, J.-B., Renwick, A., Rose, J., Setälä, M., & Suiter, J. (2021). Deliberative mini-publics: Core design features. Bristol University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.51952/9781529214123

8 Curato, N., Hammond, M., & Min, J. B. (2019). Power in deliberative democracy: Norms, forums, systems. Springer International Publishing. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95534-6

9 Devillers, S., Vrydagh, J., Caluwaerts, D., & Reuchamps, M. (2021). Regular issue. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 17(1), 35. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.961

10 Dienel, P. (2002a). Die Planungszelle. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/stabsabteilung/01234.pdf

11 Dienel, P. (2002b). Die Planungszelle: Der Bürger als Chance (5. Auflage, mit Statusreport 2002). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-322-80842-4

12 Dillard, K. N. (2013). Envisioning the role of facilitation in public deliberation. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 41(3), 217–235. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2013.826813

13 Doerr, N. (2018). Political translation. Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/9781108355087

14 Dryzek, J. S. (2000). Deliberative democracy and beyond. Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/019925043X.001.0001

15 Dryzek, J. S., & Niemeyer, S. (2008). Discursive representation. The American Political Science Review, 102(4), 481–493. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055408080325

16 Einstein, K. L., Palmer, M., & Glick, D. M. (2019). Who participates in local government? Evidence from meeting minutes. Perspectives on Politics, 17(1), 28–46. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S153759271800213X

17 Elstub, S., & Escobar, O. (Eds.) (2019). Handbook of democratic innovation and governance. Edward Elgar Publishing. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4337/9781786433862

18 Escobar, O. (2019). Facilitators: The micropolitics of public participation and deliberation. In S. Elstub & O. Escobar (Eds.), Handbook of democratic innovation and governance (pp. 178–195). Edward Elgar Publishing.

19 Fung, A. (2003). Survey article: Recipes for public spheres: Eight institutional design choices and their consequences. Journal of Political Philosophy, 11(3), 338–367. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9760.00181

20 Fung, A. (2007). Minipublics: Deliberative designs and their consequences. In S. W. Rosenberg (Ed.), Deliberation, Participation and Democracy (pp. 159–183). Palgrave Macmillan UK. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1057/9780230591080_8

21 Goodin, R. E. (2000). Democratic deliberation within. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 29(1), 81–109. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1088-4963.2000.00081.x

22 Harris, C. (2019). Mini-publics: Design choices and legitimacy. In S. Elstub & O. Escobar (Eds.), Handbook of democratic innovation and governance. Edward Elgar Publishing.

23 IAP2. (2006). Public participation toolbox. https://icma.org/sites/default/files/305431_IAP2%20Public%20Participation%20Toolbox.pdf

24 Kahane, A. (2021). Facilitating breakthrough: How to remove obstacles, bridge differences, and move forward together (First edition). Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

25 Karpowitz, C. F., & Mendelberg, T. (2014). The silent sex: Gender, deliberation, and institutions. Princeton University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9781400852697

26 Landemore, H. (2020). Open democracy: Reinventing popular rule for the twenty-first century. Princeton University Press. https://www.degruyter.com/isbn/9780691208725. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9780691208725

27 Landwehr, C. (2014). Facilitating deliberation: The role of impartial intermediaries in deliberative ini-Publics. In K. Grönlund, A. Bächtiger & M. Setälä (Eds.), ECPR studies in European political science. Deliberative mini-publics: Involving citizens in the democratic process (pp. 77–92). ECPR Press.

28 Mansbridge, J., Hartz-Karp, J., Amengual, M., & Gastil, J. (2006). Norms of deliberation: An inductive study. Journal of Public Deliberation, 2(1), Article 7. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.35

29 Mendelberg, T., Karpowitz, C. F., & Oliphant, J. B. (2014). Gender inequality in deliberation: Unpacking the black box of interaction. Perspectives on Politics, 12(1), 18–44. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592713003691

30 Molinengo, G., & Stasiak, D. (2020). Scripting, situating, and supervising: The role of artefacts in collaborative practices. Sustainability, 12(16), 6407. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3390/su12166407

31 Moore, A. (2012). Following from the front: Theorizing deliberative facilitation. Critical Policy Studies, 6(2), 146–162. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2012.689735

32 Rough, J. (2002). Society’s breakthrough! Releasing essential wisdom and virtue in all the people. 1st Books Library.

33 Ryan, M., & Smith, G. (2014). Defining mini-publics. In K. Grönlund, A. Bächtiger & M. Setälä (Eds.), ECPR studies in European political science. Deliberative mini-publics: Involving citizens in the democratic process (pp. 9–26). ECPR Press.

34 Scharmer, C. O. (2009). Theory U: Learning from the futures as it emerges (1st ed.). Bk Business. McGraw-Hill distributor. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/alltitles/docDetail.action?docID=10315452

35 Scudder, M. F. (2020a). Beyond empathy and inclusion: The challenge of listening in democratic deliberation. Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197535455.001.0001

36 Scudder, M. F. (2020b). The ideal of uptake in democratic deliberation. Political Studies, 68(2), 504–522. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719858270

37 Setälä, M., Grönlund, K., & Herne, K. (2010). Citizen deliberation on nuclear power: A comparison of two decision-making methods. Political Studies, 58(4), 688–714. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2010.00822.x

38 Steel, D., Bolduc, N, Jenei, K., & Burgess, M. (2020). Rethinking representation and diversity in deliberative minipublics. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 16(1), 46–57. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.398

39 Strandberg, K., Himmelroos, S., & Grönlund, K. (2019). Do discussions in like-minded groups necessarily lead to more extreme opinions? Deliberative democracy and group polarization. International Political Science Review, 40(1), 41–57. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0192512117692136

40 Trénel, M. (2009). Facilitation and inclusive deliberation. In T. Davies & S. P. Gangadharan (Eds.), Online Deliberation: Design, Research and Practice (pp. 253–257). CSLI Publications.

41 White, K., Hunter, N., & Greaves, K. (2022). Facilitating deliberation: A practical guide. MosaicLab.

42 Wyss, D., & Beste, S. (2017). Artificial facilitation: Promoting collective reasoning within asynchronous discussions. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 14(3), 214–231. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2017.1338175

43 Young, I. M. (2002). Inclusion and democracy. Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/0198297556.001.0001

44 Zubizarreta, R. (2014). From conflict to creative collaboration: A user’s guide to dynamic facilitation. Itasca Books.